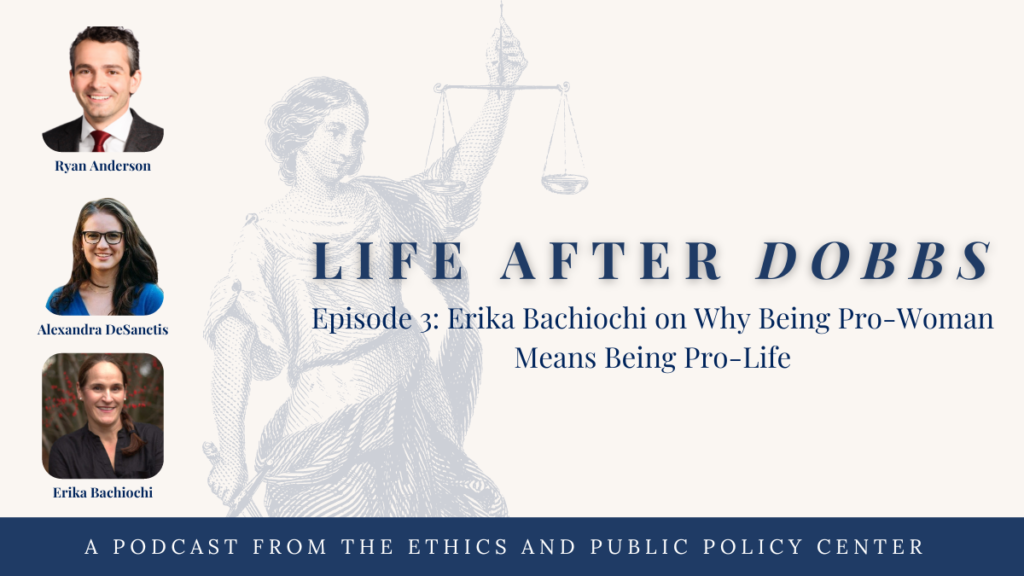

In the third episode of EPPC’s Life After Dobbs podcast, hosts Ryan T. Anderson and Alexandra DeSanctis talk with Erika Bachiochi about why so many early feminists were pro-life, the unique ways that abortion harms women and men, how to have difficult conversations across profound disagreements, and more.

Listen on:

Show Notes

Guest

Follow Erika on Twitter: @erikabachiochi

Click here to learn more about Erika’s book The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision.

—

Hosts

Ryan T. Anderson (@RyanTAnd)

Alexandra DeSanctis (@xan_desanctis)

Order Ryan and Xan’s new book Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing today!

Click here to learn more about EPPC’s Life and Family Initiative.

—

Life After Dobbs is a production of the Ethics and Public Policy Center. For more information, follow us on Twitter (@EPPCdc) or visit our website at eppc.org.

Produced by Josh Britton and Mark Shanoudy

Edited by Sarah Schutte

Art by Ella Sullivan Ramsay

with additional support by Christopher McCaffery and Alex Gorman

Episode Transcript

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Welcome to Life After Dobbs. I’m Alexandra DeSanctis, and together with Ryan Anderson, I’m the co-author of the new book Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing.

Today, we talk with Erika Bachiochi, a legal scholar and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in the Life and Family Initiative. Her work focuses on equal protection jurisprudence, feminist legal theory, Catholic social teaching, and sexual ethics. Erika is the author of two influential law review articles on abortion and the constitution. She’s also a senior fellow at the Abigail Adams Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she founded and directs the Wollstonecraft Project. She’s the author of the recent book, The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision.

Ryan T. Anderson:

So Erika thanks for joining us. Today we hear a lot that if you’re a feminist, you have to be pro-choice. And it seems to be almost a one-for-one correspondence that to be a feminist is to be pro-choice, but historically that’s not true. Many of the early pioneers of the women’s rights movement, many of the early feminist leaders thought that being pro-woman meant being pro-life. Could you share with the listeners why the early women’s rights advocates were also pro-life advocates?

Erika Bachiochi:

Sure. Thanks so much for having me on. I’m so glad you are doing this right now and congrats on your new book. I guess the best way to think about it is that they understood themselves because of advances in embryology at the time–which was also the cause of the lobbying that the doctors did then to extend kind of common law protections into more statutory protections for unborn human beings all the way from the earliest stages, at conception–they understood themselves to be mothers when the child was first conceived in their womb. So as they understood those advances in embryology, they understood that that took place much earlier than had been understood before in terms of quickening or things like that. One of the people I point to most frequently is Victoria Woodhill, mainly because she’s an incredible radical, she’s not a Christian at all. She had very different views about marriage and divorce than I have. But I think because of that, it’s helpful to see that she was this outspoken advocate of constitutional equality for women. She was the first woman to run for president, the first woman to testify before Congress. And she really championed the rights of children, but as she said, rights that begin while they remain the fetus. So I always like to give her big quote from 1870, which she wrote… Remember this is two years after the ratification of the 14th Amendment which these women were very much aware of because many of them were pushing to see women’s rights recognized in those reconstruction amendments, some of them all the way to the Supreme Court. So she says “many women who would be shocked at the very thought of killing their children after birth deliberately destroy them previously. If there is any difference in the actual crime, we should be glad to have those who practiced the latter, meaning abortion, pointed out. The truth of the matter is that it is just as much a murder to destroy life in its embryonic condition as it is to destroy it after the fully-developed form is attained for it is the selfsame life that is taken.” And one of the reasons I like to point to her is because that argument is just an excellent pro-life argument. That regardless of what the form of the child is at the very earliest stages, it is the same life that then extends and develops throughout its time in utero, and then of course, throughout its entire life once it’s born and then through adulthood. So I think it’s just an excellent argument. The second thing I would point out apart from them, just understanding that this was a human being to whom they owed duties of care was that they also recognized that the more abortion became available, the more it would tend to put more sexual power in the hands of men. And this was something they were really very much fighting. They were fighting for their own self-determination, you could say, when it came to sex. They were fighting marital rape, they were fighting the male presumption, just because of male power, but also greater libido to just assume that they could have sex with women even their wives. And so they really believe that by kind of decoupling sex from reproduction, that this would do great harm to women. And so they really pushed for what they called voluntary motherhood, which is not kind of the equivalent of what pro-choicers call forced motherhood in any way or the adverse of that. It’s actually just this idea that when a woman is not able, willing whatever to have a child at that point in her life, that abstinence is really the proper response and that that would be harder for men, but it is really what the best response to the asymmetries of reproduction would require.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

I really appreciate that kind of overview. And I think–I grew up pro-life and in the pro-life movement, I’ve often heard pro-lifers say the early feminists, the first wave feminists, that the suffragists were all pro-life, but typically it’s kind of couched as they were against abortion because they believed the unborn child was human, which of course is true. But I think that secondary piece of this is actually not good for women. This is not the proper response to what it means to be a woman, what it means to be a mother. This is not actually a feminist proposal is a really important component of that. So I think conversely, we hear a lot from abortion supporters that, that we need abortion because women can’t be free and equal otherwise. We talk about this a lot in the book, we cite your work at great length in our second chapter on this topic. And we argue that as you do that the opposite is true, right? That abortion is actually bad for women. And yet from abortion supporters, rarely do they say abortion is this wonderful thing that needs to be celebrated. It’s usually, “it’s kind of icky, we wish it weren’t true, but women just need this.” And so could you tell us a little bit about why, perhaps at a fundamental level, abortion is actually not good for women. It doesn’t make women free and equal.

Erika Bachiochi:

Yeah. I mean, the more I get into this and further into both their arguments and response is that you really see how sad of an argument it is. It’s like, because society has really failed women and failed to respond…The way that those early women’s rights activists were urging society to really be hospitable to women and the children, they bear and disproportionately care for in early childhood and all of that, because society has failed in such a way, we have to resort to this kind of need to like take out our children and it’s this really sad response, which frankly is the way that I think in the early abortion rights movement in the 1970s, you heard more of that, that it was more like a necessary evil. And so the way in which it’s been contorted into this positive good that women’s equality relies on it, I think is really where you see the real corrosive nature of the problem, which I know you will be bringing out in your book, and the way it’s corroded all different elements of society. But I think the way that I have had some success in helping people see is that there’s a real male normativity. I mean, you can say that’s a feminist way of talking about it, and I guess that’s true, but there’s a real male normativity in thinking of equality as the capacity to walk away from the sexual act. So I think it’s really helpful to start with just the reality, the biological reality of reproductive asymmetry, that when men and women engage in this sexual act together, it is women’s bodies who have the capacity to bear children, not men’s. And so men have the capacity literally to walk away, whether it’s walk into the other room or walk away entirely from their responsibilities, they can walk away. And so there’s this idea that in order to have this kind of equal autonomy–I mean, that’s what it is walking away from responsibility…’I belong to myself, I can walk away’ that women have to be able to walk away from the child too. But of course the real distinction is that they’re not just walking away, they’re engaging in this affirmative violent act. And so it’s a real, and now we have this move that which is basically now we need abortion order to attain market equality. So it’s now in order for women to be market equals, to earn as much as men, then they really need to have this kind of equal autonomy. And I understand that to be really giving in, really capitulating, to the logic of the market, instead of understanding that the family and the relations of the family, the relations of mothers and fathers to their children, all of those are really first, they come first, they should have priority in thinking about the goods of society, because they’re the most basic relations. And if we don’t get those right, then of course, everything else is gonna be kind of built upon a lie.

Ryan T. Anderson:

So following up on that, everything you just said about the realities of the asymmetry of reproduction, and then how we build a society that recognizes and respects and honors that asymmetry and what it expects from both men and women, we agree with entirely and we cite you throughout the book in various parts of the book on this this insight that you’ve had. Our book is primarily geared towards an audience that’s already inclined to be pro-life, it’s meant to kind of equip them with a more overarching encompassing argument about the pro-life movement than it is about persuading skeptics or persuading people who don’t already agree with us. We think it’s accessible to people who don’t already agree with us, but those weren’t our primary audience in mind. But one of the things that Alexandra and I both really admire about you is a lot of your work really is geared towards audiences that don’t already agree with us. And you’ve done a lot of conversations and debates and presentations, symposia, where you’re in somewhat hostile territory and you’re not preaching to the choir. What is your best advice for listeners for those conversations? I mean, how should we think about everything you’ve said about why abortion is bad for women, the realities of asymmetrical reproduction, how do we help communicate those truths to someone who might be persuaded by the ‘shout your abortion’ movement. How do you begin to have those conversations?

Erika Bachiochi:

Huh. Yeah, I have to say that it’s really, in my view, really the fruit of a lot of prayer and just really wanting to I–and many of your listeners may not know this–I come from the perspective of having been a women’s studies major at Middlebury College in the 1990s, I was one of the leaders of the women’s center there. I volunteered one summer handing out pamphlets or whatever for for Bernie Sanders. So I come from that perspective. And so I really felt kind of called to be the bridge to what I take to be a much more pro-woman stance than I used to believe. People were bridges for me, and so I feel a real responsibility to be that bridge for others. And I was not convinced by some people hollering at me and kind of owning me in any way. I have to say I was first really moved by the presence, the sheer presence of Helen Alvare. I actually don’t remember a thing that she said, but she came into a classroom when I was at American University for a semester. This is in the 1990s, she was working for the bishops, and she just had this joy and peace about her. And just the love of her interlocutor that the interlocutor, the pro-choice interlocutor, did not share for her, let me just put it that way. And I think that that really remains the best possible way to interact with our interlocutors is immense charity and a real belief that–and this is an Aristotelian view–that they are aiming for some good. And so what is that good? Find it, search for it, and try to pull it out and try to–it’s not so much find common cause as though we’re gonna go together to the legislature and lobby for some common bill–it’s like finding common cause as human beings. Generally, I mean, obviously there are some people who are steeped in evil and there’s not much you can do. And they can’t hear me and all of that, but I think many, many people, especially the people I’ve talked to–Robin West, Reva Siegel, Eva Feder Kittay–they are aiming at some good. So this is what I would say is that I always begin with the care ethic. I tend to steer clear of rights talk. I’ve learned that a long time ago from Mary Ann Glendon, but I think that that kind of gets us in this kind of Lockean framework where we’re all battling about rights, which sometimes can seem incommensurable. But I think if we talk instead about the duties of care we owe to one another and the need for real responsibilities for one another that mothers have responsibility for their children, fathers have responsibilities to their children, and society owes responsibilities to both mothers and fathers. I think talking about those kinds of interweaving obligations and talking about the duties we have to children first and foremost, putting children first, but not, of course, just unborn children, just children and their vulnerability and dependency. That’s why we ought to care for them, but that mothers need care and fathers need help in giving mothers and children care. And I think it is part of just being humane in this, trying to find the common human element in it that I think has been–and not at all, making my strong arguments, which I always do, but it’s just trying to find that first, because I don’t think there’s a way of bringing people at all around to one’s position by starting as enemies. I’ll probably hack his statement here, but Abraham Lincoln talked about the best way to win over your enemies is by making them your friends. And that’s kind of the way I go about my work

Ryan T. Anderson:

And you’re too humble to toot your own horn, so let me do it for you. For our listeners, a great example, the embodiment of everything Erika just said, in terms of how she thinks about going about doing this, is a 90-minute-long episode of the Ezra Klein Show produced by the New York Times where Erika’s the only guest. And so for an hour and a half Ezra’s grilling her on questions about being a pro-life, pro-woman advocate. And Erika, you don’t pull your punches, you make strong arguments but you make them charitably and you make them accessible to someone with a pretty different foundational worldview than the one that you hold to, the one that Alexandra and I hold to. So I would commend our listeners, as soon as you’re finished listening to this episode of the podcast, look up that episode of the Ezra Klein Show from a couple weeks ago where Erika was the guest, because it’s a really a prime example of how to have those conversations.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Yeah. I appreciate everything you do, Erika. And in particular, that last insight you were sharing about not only befriending those who disagree with us, but really trying to give them their best argument when you’re responding to them. I did a debate a couple months ago with Jill Filipovic, who’s a pro-abortion attorney and writer. And I really liked her personally. We spent time together before and after the debate, the debate was respectful, productive. And I like her a lot. I don’t think we’re good friends or anything, but I liked her company. And during the debate, she made this closing comment about, “if I had gotten pregnant in my twenties, I would’ve wanted abortion because my life would’ve gotten off track, essentially. And all these things that I now have, I wouldn’t have had, I wouldn’t have found my husband.” And I’ve thought about that a lot since then. I’ve written a piece about it, in fact, because I think that’s a really human feeling, right? The feeling that we all want to control the outcomes in our lives, we want to be in charge of what’s going to happen to us. And obviously I don’t condone abortion as a means of doing that, but I can very much relate to the sense that we want to be in control. We all kind of have this desire to be autonomous, to be independent, to make good and beautiful things happen for ourselves. So I think a lot of pro-abortion people are coming from a place that many of us can relate to on that score. But I wanted to pull out another point that you mentioned, which is, you said “Lockean.” So could you explain for our listeners where John Locke and his arguments, his political theory, kind of fits into all of this for your thought?

Erika Bachiochi:

Yeah. So Locke kind of remains this central figure if only because Americans really tend sometimes, without even knowing we’re doing it, to lean on Lockean assumptions about human beings. I won’t bore your listeners with all sorts of references to his Second Treatise on Government or something, but I think it’s easy enough to say that while he can be totally credited with providing this kind of theoretical foundation for the Declaration of Independence, for modern self-government, to counter the divine right of kings. I think it’s helpful, as some wiser than I have said, to kind of keep Locke in a lockbox. I really like that idea: use him for what he was helpful for. The founders weren’t relying on him for every single way they thought about things. They certainly didn’t think about human relationships in this contractual, consensual sense at all. They were by and large Christians, even Deists didn’t think that way. So I think there’s a way in which, because of the receding of Christianity, there’s a way that everyone tends to in this kind of liberal era use Locke as the way they think, especially about rights. And so in my new book, The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision, in which I lean on Wollstonecraft’s view of rights as necessary for carrying out our responsibilities, I’m trying to get back to a more classic understanding of right, or our capacity or freedom to do things that we are obligated to do. And so that’s the way Wollstonecraft, she understood herself that we were interdependent mothers and fathers fully in relation to each other. But Locke, with his kind of mythical state of nature, especially if you read him a bit more as a Hobbesian–that’s a big debate that goes on–there tends to be this idea that rights are based in self-ownership and autonomy, and property rights for him are really paradigmatic. So you can hear this, I mean, you see this, Xan, in your own work because you respond to it so well, but there’s this kind of Lockean way of thinking about abortion where the pregnant woman owns her own body. And just like a property owner who owns his own property has this absolute right to–in our tradition although it’s been changed some–kill anyone who comes upon it, it’s like this woman has this absolute property right to expel the child who, if she hasn’t consented to the child being there, is like a trespasser, an invader. And then if she consents is more like an invited guest, this is very much like a Lockean way of thinking about things. And I think it’s just a really poor way of understanding any kind of human relations. I think Locke probably thought the same, although we can argue about that as well, but the reason why pro-lifers believe or understand that the unborn child has a right to life or that we owe duties of care to that child is not because of any autonomy that child has. It’s literally because the child is vulnerable, defenseless, dependent on its mother and the mother is the only one who can give that child care–it’s like this existential dependency. So even thinking through the problem with Lockean rights as your framework is a really false way of thinking it through. And hopefully by the time this airs, although maybe later, I have a piece coming out in the New York Times about kind of this exact framing that I think it’s been really kind of a false footing upon which a lot of us have been engaging in the the question of abortion.

Ryan T. Anderson:

That New York Times [article], at least the draft that I’ve read of it, it’s outstanding. So I encourage our listeners, depending on when it’s published and when this episode is published, do a Google search, find it, read it, share it it’s really a great encapsulation of how the Lockean personhood and autonomy debates have kind of corrupted much of our discourse about abortion. And I want to follow up on that because you had mentioned in the answer to one of your earlier questions one of our earlier questions was you cited Mary Ann Glendon’s book Rights Talk, and how you try to steer clear of rights talk. And yet the title of your book is The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision. And I commend that to listeners, and if you don’t have time to actually read the book, although you should, we did an event EPPC co-sponsored with the Catholic Information Center where Erika spoke and then Mary Eberstadt and Ashley McGuire gave responses, and then we had a Q&A with the panel and the audience, and that’s another thing that you could listen to learn more about Erika and her work. But the title was The Rights of Women. And I want to ask you: how do duties and virtues fit in with that? How did Wollstonecraft, how does someone like Glendon, how does someone like you think about the interrelationship of rights, duties, and virtues, and then how do you apply those three concepts to the abortion debate? How would enlarging our moral vocabulary beyond just rights to also include a sound understanding of rights, a sound understanding of duties, and a sound understanding of virtues? How does that then map onto some of the abortion debates?

Erika Bachiochi:

Yeah, the single line, if I can get it right, is that rights are necessary to virtuously carry out our duties. And so that’s a more classical understanding and I argue it’s the understanding that Wollstonecraft had in her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which also has rights in the title. But as many scholars before me have pointed out, it is far more about duties and virtue than it is about rights. So rights and freedom are really means for us to to live virtuously and thereby attain kind of personal and societal happiness. And if you look around at your life, rights don’t come first, rights again are necessary, but it’s really our obligations to one another in the family. Because we’re, as the ancients knew, parts of greater wholes, that we’re all deeply interdependent on one another. And so we have these obligations to one another, and that, as Wollstonecraft saw, that really what a society does properly is help individuals help persons carry out those obligations. That’s how a society functions well is when people are carrying out their obligations to one another. Why? Well, because those obligations are fulfilled and therefore then the people who are on the other side of the obligations have their needs met, but also because carrying out our obligations, especially with virtue…that helps us to flourish, right? It is not in a self-seeking way, but in a way that helps human beings to live according to reason. So, I think it’s Cicero who talks about how virtue is fully-formed reason that we need to be living according to the highest principle in us. And as these rational animals, or rational creatures as Wollstonecraft would call us, reason is that highest principle. To live according to reason is to not to have reason govern our appetites. Our appetites, our passions, our lower passions are good and they have their own ends, but they’re not the complete end of human beings. Our passions for sex and for food and our need for all those things, they have to be governed by higher principles. And and that’s what virtue is. The virtue of temperance, or self government, or sexual self-mastery, integrity, all of these things are really important for just living out human relations. One of the things Wollstonecraft was really good about was how the want of male chastity was this massive cause of women’s commiseration. But she would say when men aren’t governed by virtue, they really live as beasts. They live like the animals do. It’s something I ask my children frequently. Like, do you wanna live like an animal? And according to your each and every fleeting desire, or do you wanna live as a human being and live according to your reason, and for Christians, that reason, we hope, comes to full flowering and is enlightened by the light of faith and grace. So, yeah, with the abortion question, obviously women are pushed by the passions of fear or other people’s coercion and all that stuff. And I think sometimes we have to have those principles governing our understanding that there’s a human child here to whom we owe duties of care. There are other people who should be called to be helping me out in the community. And and so that’s a better way of framing this thing, that duties come first. And so fulfilling those are what’s going to bring happiness. The one thing I also want to respond to, Xan, when you were talking about this desire for control is that we have, I mentioned on the Ezra Klein Show that it’s so sad to me that so many, and I mean I felt this way too as a pro-choice feminist, that we have this ex ante fear or decision that we don’t wanna have children and we only want to have a couple. And it’s so sad because when those of us who have had children, each one of them, even though it’s hard, and even though it’s probably the hardest work we do, it opens up this totally unbidden world to us that we couldn’t have chosen, that we couldn’t have made ourselves. And so it opens up this horizon that is so much beyond like our stultifying, navel-gazing way of thinking about what our lives could be. And children really do that. They open up the future to us in a way that I think our own plans and desires and designs tend not to.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Yeah. I love that insight because when I heard Jill making this comment, I felt so sad for her that she felt that way because it was obviously a very sincere and deeply rooted feeling. And while I can relate to it, my first thought was most of the wonderful, beautiful things in my life were totally unpredictable, right? Who I was born to, the fact that I was raised Catholic, the fact that I met my husband when and where I met him and who he is, none of these things are something I produced or controlled or decided for myself, right? And I think most people would say most of their biggest blessings are things they never would’ve predicted or imagined for themselves. And so I think it’s this kind of false idea that we can be gods, that we can kind of take control of everything and produce the best possible lives for ourselves, and abortion kind of fits into that worldview. But you kind of mentioned this in your last point and earlier on in our conversation that the pro-abortion feminist reliance on abortion is really a response to the failures of men, or as they see it, the failures of men to be present, or the things that society ought to be doing for women that aren’t done that therefore make abortion, as they would put it, necessary. And I know you talk about this a bit in your book, but what should our society ask of men? What should men do that might make childbearing, childrearing easier for women, and therefore reducing the idea that women need abortion?

Erika Bachiochi:

Yeah. That’s like the $60,000 question as far as I’m concerned because it’s been this fascinating thing to watch, how people respond to my work. So, there’s this thinker on the right who says, “Erika just wants women to control men.” And then there’s people on the left who say, after the Ezra Klein thing, “she just wants women to be the ones responsible for sex. And what about men?” And I come out with this Wollstonecraft response, which is actually: we all ought to be responsible for ourselves in terms of our own kind of self-governance and really learning the virtues of self mastery, which I think can be and must be really taught as as children. And so that would be the first thing I would say is that the experience of fatherhood which, by the way, both of these men who were responding to me on either side have and relish, is really the single best response, as I say, to kind of reproductive asymmetry. Engaged fatherhood, Brad Wilcox has done so much good work on this, he’s shown that really engaged fatherhood where men are really not necessarily doing half of the chores or something like that, but are really engaged emotionally in the lives of their wives and children is really the place where you see women become happiest. Those are the happiest wives and you see all sorts of indicators that when fathers are engaged in the lives of their children, those children do so much better. So I think engaged fatherhood is the number one thing. And I think in our society where you see declines in real wages for working-class men, that we need to find ways to deal with that crisis of especially blue-collar men, kind of out of work. I think the push–this is getting into another issue–but the push for college education for everybody has really left a lot of men behind. And we have to be finding ways to help them economically so they can participate. But I also think that there’s a way in which restricting abortion and you see this, so Jonathan Klick–I think it’s Klick, K-L-I-C-K–has done work showing that when the costs of sex are increased people change their sexual behavior. And so I think there’s a misconception that when abortion is restricted, we’ll have SO many out-of-wedlock babies. And that’s not quite right, there is going to be a shift where people, at least that’s what economists show in pointing to other sorts of things, pointing to requirements of child support and enforcement of child support that you see men change their sexual behavior when they realize they’re gonna be on the hook for their whole lifetime. And so how do we do that? I think these are really big questions that a lot of us have to be working at. And that is where I see, and this is what I kind of argue for in my book, that we’ve always understood, conservatives and I think people on the left too, that motherhood is this kind of constitutive feature of women, but I think fatherhood really has to be understood as this constitutive feature of men. Whether or not they become [fathers]. It’s really, what is it to be a father? What is it to live out fatherhood in a way that is, and I can’t answer this myself, but I think it’s a noble quest at self-mastery for the good of others. Those are kind of the questions that I think we need to be working at, especially on the right.

Ryan T. Anderson:

I love everything you said about fatherhood. It rings true to me. I would say the greatest blessing in my life has been our three children–God willing, we’ll have more. And as Alexandra said, they’re not something that we could have ever planned or manufactured or produced. They’re received as gifts. And then they bring out the best in you. That’s not to say it’s easy. It’s not to say that there aren’t sleepless nights or frustrating days. But it’s to say that all those kind of sacrifices bring out what’s best in life, to a certain extent. And I wanted to mention another book, when you were talking about the sexual economics, a book by a friend of ours, Mark Regnerus, a professor of sociology at the University of Texas in Austin. His book Cheap Sex is also really good in doing a sociological, economic analysis of how sexual behaviors change based upon the costs of sex and how in our modern culture sex has become cheap, and what that therefore entails. But since we’re running out of time, I want to ask, we’re recording this before Dobbs has been officially released. But it could be released any day now. Especially in light of the individual who was arrested at 1:43 in the morning carrying a gun outside of Justice Kavanaugh’s house. So we don’t know if the Court’s going to accelerate their schedule for getting these opinions out, but on the assumption that something like the leaked draft becomes the majority opinion and that Roe is finally overturned, what’s your advice for the pro-life movement? What do we do now? Where do we go from here? You have a captive audience of listeners. What are the marching orders that you would give give to listeners?

Erika Bachiochi:

Yeah, so my view is that in addition to really pushing in, especially the blue states like mine in Massachusetts, to really push back on this crazy radical pro-abortion fanaticism in so many of these states, which in some states edges onto allowances of infanticide, I would say that the real singular thing that we need to be doing is working at family policy. And so both the left and the right have been talking about this for a while. But I think we’ve gotta get in the same room and hash things out. I think there’s all sorts of ways. Part of my book–it’s funny, on the Ezra Klein show, we talked so much about sex and contraception and abortion, we got at the end about family policy, but so much of my book is about kind of work and economic transitions and what it meant for women especially to move from the agrarian through industrialization and now into the kind of modern kind of workplace and what all of that means and what the kind of economic transitions that have taken place mean for the family today. I think the right tends to not see those kinds of economic transitions as important and kind of devastating to many people as they are. And so getting a hold on those and trying to see that it’s really difficult. There are some wealthy people–and some middle class but mainly wealthy people–who can really care for the needs of the family without any sorts of support. They can live in a libertarian atmosphere and it’ll be fine, but what are the ways in which families who have really been rent by by decline of manufacturing jobs, decline in men’s real wages, low-paying service industry jobs, all sorts of these kinds of things. The massive increases in the cost of housing, the cost of insurance, the cost of all these kinds of things. Plus the way in which assortative mating has made the income gap between the professional class and the working class, the way in which the wealth gap and the income gap can really be blamed in part on assortative mating as well as all these other economic transitions. How is it that we can help families, because without good families that aren’t akin to industrial-era families where both parents especially among the poor and working classes were sent off to work and children had to fend for themselves or now are sent into daycare two weeks after they’ve been born for hours and hours on end, we have to respond in kind of the same way. I’m not saying that we need a kind of New Deal, although a New Deal with different assumptions would be good, but I think there are responses that family policy can tend to while taking into consideration the unintended consequences that have come to pass with other kinds of growth in welfare. I wouldn’t see these as growth in welfare. I’d see this as a way to kind of share the economic cost of raising children which families do for everybody. And so how do we share those costs better across the society? Because if we’re not doing that, we have a lot of what economists call freeloaders, right? People who benefit from other parents–other adults raising children–they get all the benefits and then those parents have those economic costs. So how can we think about doing that? And that’s really where I think a lot of us need to be headed and I know EPPC is very much primed to be headed in that direction.

Ryan T. Anderson:

Yeah, thank you. I’ll just mention for listeners that I think our colleague Patrick Brown at EPPC, who’s in the Life and Family Initiative with you and Alexandra, he’s been doing a lot of really good work on family policy. I would suggest to listeners as a place to start, he had a New York Times op-ed, I think it was sometime either in late April or early May. I think it was probably early May, it was shortly after the Alito opinion was leaked and it was titled something like “The Pro-Family Agenda Republicans Should Adopt After Dobbs.” I’m sure the New York Times had a more concise headline than that, but that was the gist of the headline. And that was also the gist of the op-ed. He was giving advice to the Republican Party on a pro-family economic agenda that took seriously economic realities, took seriously market realities, but also took seriously duties that we owe to families, duties that we owe to women bearing children.

Ryan T. Anderson:

And that would be something I would commend to listeners to check out. And Patrick has a whole host of other essays that you can find on the EPPC website.

Erika Bachiochi:

And I would second Patrick’s work, absolutely. I’m very much a fan.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

All right. Well, on that note, we want to thank you, Erika, so much for joining us, for all your insights today. We really appreciate it.

Erika Bachiochi:

Thank you.

Alexandra DeSanctis:

Thanks for listening to Life After Dobbs. Ryan and I are co-authors of the new book, “Tearing Us Apart: How Abortion Harms Everything and Solves Nothing,” which you can order now. If you enjoyed our conversation, please subscribe, leave a review, and share it with a friend. This podcast has been sponsored by the Ethics and Public Policy Center. You can learn more about our work at eppc.org, including our Life and Family Initiative.