Published October 23, 2023

I visited Sheikh Yassin, the founder of Hamas, one desolate rainy morning during the first Intifada. I was a writer for Time, and on that day, Jamil Hamad, Time’s Palestinian stringer, drove me down to Gaza from my hotel in East Jerusalem.

On the Nablus Road, we passed the shell of a burnt-out Israeli school bus. Jamil’s car had blue Palestinian license plates and a big sign in the windshield that said PRESS. He spread a checkered black-and-white Palestinian kaffiyeh on the dashboard, just to make sure, but the shebab (young Palestinians) threw stones at us anyway. They did it satirically—their rough little joke. We ducked and flinched and laughed at them and waved. The boys had good arms. I told Jamil the Yankees could recruit pitchers here.

A few Israeli checkpoints detained us on the way. The IDF soldiers didn’t like the blue plates or the kaffiyeh, so their manner with Jamil (a gifted and impartial reporter) was hard and overbearing. But they were courteous enough to me, a journalist from the outside world.

We picked our way among side roads on the edge of Gaza City, and at length arrived at an unprepossessing, one-story house. Jamil had called ahead to arrange our visit. The guards outside vetted us and presently we joined a throng of Palestinians—retainers, pilgrims, petitioners—assembled in the reverent hush of a big, bare reception room.

The half-blind, paraplegic imam Yassin had started Hamas a year earlier, in 1987. Its founding charter called for the extinction of Israel. Born in Ashkelon in the old British Mandate of Palestine, Ahmed Yassin came to Gaza with his family as a refugee. He was paralyzed in a wrestling accident with a friend when he was 12. Though half-blind, he was widely read in philosophy, religion, and economics before he turned to the politics of nationalism and exile. He worked at setting up a Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood and founded an Islamic charity in Gaza. In 1984, he was jailed, briefly, because his charity’s work apparently included the secret stockpiling of weapons.

Standing in a corner of the reception room, Jamil and I waited for half an hour . . . an hour. At last, there arose a stir among the faithful—the rustling of suddenly agitated birds—and the Sheikh, pushed in a wheelchair, emerged from shadows on the far side of the room.

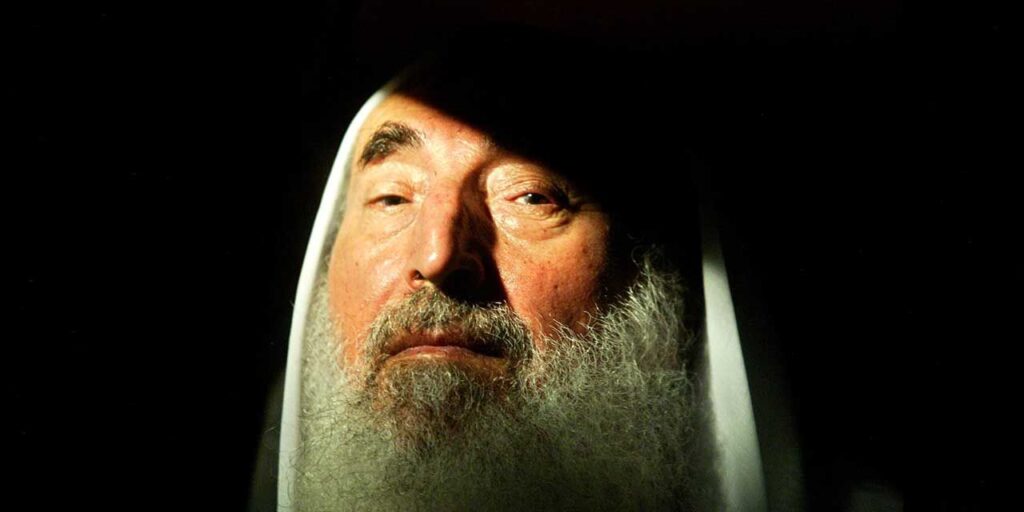

He was a memorable apparition—long-bearded, with a head too large for his body and the face of a stylized religious icon. He might have been painted by El Greco: the white-robed saint and prophet, come to visit the earth, as it were, from another world. He moved among his damp and hopeful followers as a sort of radiance. He received their obeisance with eyes sightless and mystic, peering past them into the space beyond. But when he came to face Jamil and me, and was told who we were, his expression became suddenly shrewd: evasive. He’ll toy with us, I thought. He is laughing a little.

And why not? I was a jerk from an American newsmagazine. He cocked his head in my direction, as though in amusement, as though indulging a child. I took out my notebook and began to ask him very ordinary questions, and though Jamil, in translating, tidied up my thoughts, so that I would not sound more naïve than necessary, the Sheikh, who lived in a universe of sophisticated danger, understood that I was no threat. The American journalist would depart Gaza as ignorant as when he came. The imam amused himself by replying to my questions (about Hamas’s attitude toward political violence, for example, or about its stated ambition to wipe Israel from the map) in Delphic riddles, open to interpretation in two or three different ways. Cat and mouse. Sleight of hand. His unseeing eyes looked at once fanatical and innocent.

But even with a naïve American, the Sheikh had to be careful. Mossad and Shin Bet were everywhere. He knew that what he said, no matter how skillful his abstractions, would probably get him killed one of these days.

We talked on. The interview was a ritual, a game that he knew well. It had a sort of murmurous ecclesiastical sound (a little like the Catholics’ old Latin mass, heard indistinctly from the back of a church). My English and his Arabic were call and response.

Of that morning with Sheikh Yassin in his house that smelled of mildew, I remember the yearning pilgrims who kissed his hand (their religion and politics indistinguishable and obliteratingly fervent). And I remember, in contrast, the Sheikh’s sly and (it seemed to me) demonic air. I thought of the scene in the 1966 movie Khartoum, in which the British general “Chinese” Gordon (a missionary and a bit of a nut, played by Charlton Heston) and the Mahdi (Lawrence Olivier) meet in person in the Mahdi’s camp. The Mahdi asks (Olivier gleefully overacting): “Is it because you are an Infidel that I smell Evil?” On perhaps the same grounds, I thought that I smelled Evil in the Sheikh, while he—if he bothered to react to me at all—sniffed out an American Evil, which had to do with U.S. support of the Jews.

A year after my encounter with the Sheikh, the Israelis nailed him. They sentenced him to life imprisonment for ordering the killing of alleged Palestinian collaborators. He served eight years in prison but was released, in 1997, in exchange for two Mossad agents held by the Jordanians. He took up the Hamas leadership again. Prison had, if anything, disambiguated his ideas and endowed them with new candor. He advocated—and implemented—suicide bombings, mass killings of Israeli civilians.

And so it was that one morning in 2004, the Sheikh, as he was wheeled from his home to the nearby mosque where he prayed, was blown to bits by a Hellfire missile fired from an Israeli helicopter. As news of the assassination spread, riots and demonstrations raged across the Middle East.

A familiar drama, of course. But this year’s iteration—starting with Hamas’s October 7 terror assault on southern Israel, which unleashed the Israeli retaliation—has become much more violent and dire: it may indeed represent the fulfillment of the Sheikh’s dreams.

Lance Morrow is the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His work focuses on the moral and ethical dimensions of public events, including developments in regard to freedom of speech, freedom of thought, and political correctness on American campuses, with a view to the future consequences of such suppressions.