Published September 25, 2023

In the first two summers of the Eisenhower administration (1953 and 1954), when I was 12 and 13 years old, I worked as a Senate pageboy. As I sat on the steps of the Senate chamber’s rostrum during long, somnolent hours of debate or roll calls or mere parliamentary idleness, I studied the senators. They were, to me, a dramatic, semi-mythological breed, famous and powerful and vivid men. (The Senate’s lone woman member was Margaret Chase Smith of Maine.) That they went about their business in the flesh, so close to me—that they now and then scratched themselves and yawned or snapped their fingers to summon me to run to the cloakroom and fetch them a chilled bottle of White Rock seltzer water—made them still more exotic: the Senate was an intimate, historic spectacle. I was a lucky boy.

I paid attention to the sound of the senators’ voices, to their regional accents (for they were politicians who raised up in an earlier time, pre-television, with livelier, more theatrical styles of speech than those appropriate to the small screen). I noticed the subtleties of how they dressed, perhaps because, in those days before network TV and interstate highways had homogenized the country, the differences might be sharp and telling. Even their faces had more regional style than now. Massachusetts’s Leverett Saltonstall, of Mayflower stock, stood ramrod straight, with neat, steel-gray hair and a pronounced Plantagenet jaw: he looked like an aristocratic lobsterman. Not far away sat Clyde Roark Hoey (pronounced HOO-ee) of North Carolina, an upcountry Confederate antique who wore a wing collar and a black string tie.

The Senate minority leader, Lyndon Johnson, was radiant with the vulgar opulence of Texas—expensively tailored in dark silk suits and wine-colored Countess Mara ties and shined cowboy boots. His shirts were monogrammed with his initials on each French cuff, something I had never seen before. Johnson would send me down to the Senate cafeteria to bring him dishes of vanilla ice cream, which he ate at his desk as he called up bills for consideration.

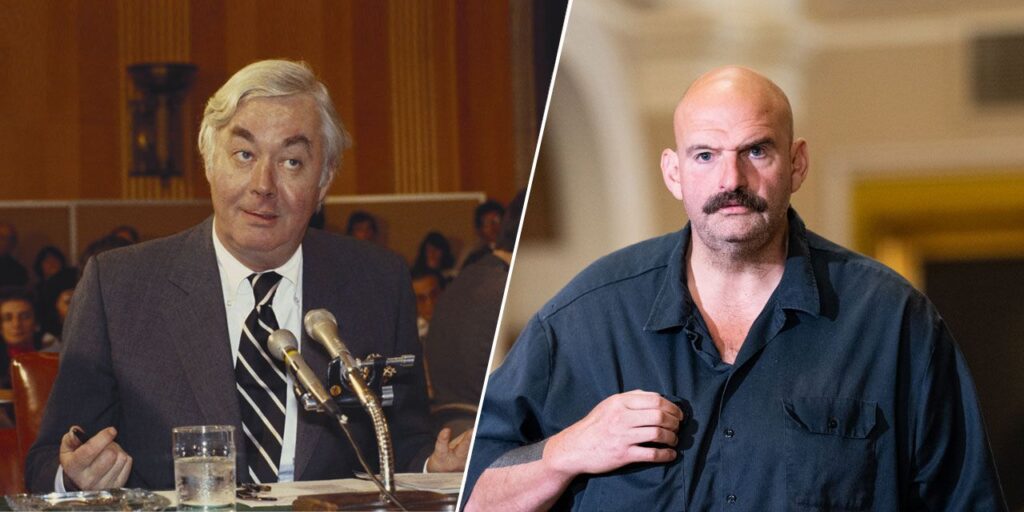

I loved the Senate. Those images from 70 years ago came back to me after I saw that the current Senate majority leader, Chuck Schumer of New York, has ruled that senators will no longer be expected to wear suits and ties in the chamber but may wear just about anything they please, a gesture intended to appease one highly peculiar man: John Fetterman, the six-foot, eight-inch freshman senator from Pennsylvania, who goes about his daily business wearing gym shorts and a hoodie. Pennsylvania’s electoral votes may be crucial in 2024. I know how Lyndon Johnson would have responded to the sight of 54-year-old John Fetterman skulking into the chamber dressed like a disturbed adolescent.

There were heroes and villains in the olden time, but they all wore suits and ties. Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin—in full cry just then—dressed invariably in cheap, rumpled, dark blue suits that he wore every day until the seats and elbows had grown shiny, whereupon he replaced them from the same rack at a local emporium. His ties were big Rotarian gravy-catchers. He smelled of alcohol. Some of his friends (Herman Welker of Idaho, for example) kept in their Senate desks a small pharmaceutical bottle of gin or vodka as a precaution against hangover. Pageboys knew such things.

John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts came to the chamber only rarely. He looked sickly and rail-thin, walking on crutches as he recovered from a dangerous back operation. He still dressed a little like a Mucker from Choate—the gray suit (from, say, J. Press) a little too big and the thin, regimental-striped tie knotted off-center and the Brooks Brothers button-down collar a little frayed. People, including fellow senators, stared at him in wonder, as if they had a premonition.

George Smathers of Florida—tall, dark, rakishly handsome—was Jack Kennedy’s pal and companion on nocturnal adventures. Smathers had thick black hair that he thickened further with Vitalis or some other bear grease. He wore dark suits and silk ties and round-collared shirts fastened at the Adam’s apple by a gold collar pin. The effect was an elegant, lock-up-your-daughters rogueishness. I wondered how he succeeded as a politician: he seemed the last man in the world an ordinary citizen would trust.

The high-minded and avocado-shaped Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois, an economist by trade, wore his trousers belted up above his belly, like an empire gown. The thick, triangular end of his flapping necktie was always shorter than the thin end. The thick end rested on his thorax like a bib.

Incomparably the best dressed man in the Senate, and perhaps in all of Washington, except for the lawyer Clark Clifford, was Stuart Symington of Missouri, whose tall, slim physique was perfectly proportioned to model men’s fashions. Like Smathers, he wore round-collared shirts with gold collar pin, and silk ties that even I (though colorblind) could tell were elaborately coordinated to match his suits and pocket handkerchief, which, in the summer, came in lighter shades of khaki or brown.

In hot, humid Washington, many senators, especially the southerners, wore off-white Palm Beach suits. The Democratic side of the aisle, where almost all the southerners sat, might look as if it had been outfitted by Sidney Greenstreet’s tailor.

The Senate of those days had its flawed characters but, despite all, a formality—an archaic dignity. Senators Schumer and Fetterman have invited their colleagues to turn the place into a smelly gym or a psychiatrist’s waiting room.

Lance Morrow is the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His work focuses on the moral and ethical dimensions of public events, including developments in regard to freedom of speech, freedom of thought, and political correctness on American campuses, with a view to the future consequences of such suppressions.