Published November 30, 2015

The Faith Angle Forum is a semi-annual conference which brings together a select group of 20 nationally respected journalists with 3-5 distinguished scholars on areas of religion, politics & public life.

“Forgiveness and the African American Church Experience”

South Beach Miami, Florida

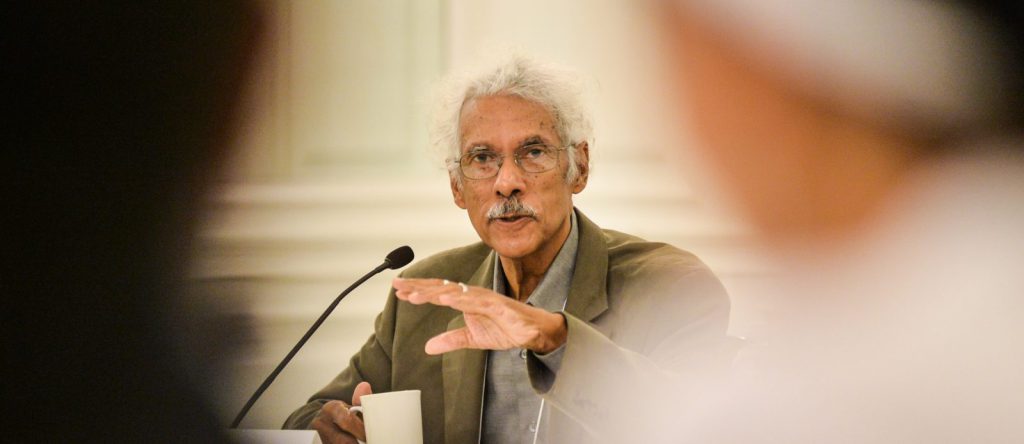

Speaker:

Dr. Albert J. Raboteau, Henry W. Putnam Professor Emeritus of Religion, Princeton University

List of participants found here

Presentation audio | Presentation video

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Thank you and welcome. Twice a year I have a lunch with several of you and we talk about what are the future topics for Faith Angle. For instance last May we could be doing right now a repeat session on one of our sessions. We had a session on the theology and ideology of ISIS. We try our best to make sure the topics we are talking about are something that are in the news now. At one of our luncheons our esteemed colleague Carl Cannon said I was so deeply moved by the response of the people in that church in Charleston; couldn’t we do something on that? And that is what we are doing this morning.

Professor Raboteau’s bio is extremely impressive as you know. He is one of the nation’s foremost scholars on African American religion, and the former Henry W. Putnam Professor of Religion at Princeton University. He is now professor emeritus at Princeton. I will just tell you this. I have spoken to two leading American historians who’ve said you’ve got the best person in the country to talk about this topic. And they will remain nameless but they are big fans of yours. Dr. Raboteau is the author of many books. Among his works are Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South and A Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African-American Religious History.

So Professor Raboteau thank you so much for coming. And we look forward to hearing from you. And then we’ll have a wonderfully robust Q and A. Thank you sir.

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Thank you very much, Michael, for inviting me to participate in this Faith Angle Forum. It was a delight to meet a number of you last night over dinner and to have already very robust discussions particularly about what is happening on campuses now in the wake of the Black Lives Matter phenomenon.

Today I’ll be speaking as you know on Forgiveness and the African American Church Experience.

“Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” (Matthew Chapter 6, Verse 12). “You have heard that it was said you shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy. But I say to you love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, and pray for those who spitefully use you and persecute you.” (Matthew Chapter 5, Verses 43-44) “Father forgive them for they know not what they do” (Luke Chapter 23 Verse 34).

The murder of nine black parishioners attending an evening Bible study class at the historic Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina has focused national attention upon racism already roiled by a succession of killings of unarmed black men and women and a child captured in some cases on cell phone videos and body cams. The pastor and state senator, Reverend Clementa C. Pickney, age 41, Cynthia Marie Graham Hurd, age 54, Susie Jackson, age 87, Ethel Lee Lance, age 70, Reverend Depayne Middleton-Doctor, age 49, Tywanza Sanders, age 26, Reverend Daniel Simmons, age 74, Reverend Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, age 45, and Reverend Myra Thompson, age 59 were shot to death by a 21 year old white supremacist Dylan Roof, who hoped to incite a race war. He had chosen the church after historical research informed him of its significant history. Some of its members were accused of plotting a slave rebellion led by a free black carpenter named Denmark Vesey who was a class leader in the black Methodist community in Charleston. After the plot was discovered and its leaders deported or executed in 1822 the church was burned to the ground. Its pastor Reverend Morris Brown fled to Philadelphia where he eventually succeeded Richard Allen as the second bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, one of the first black denominations in the country. Ironically after the Civil War the church was rebuilt according to the architectural plan of Vesey’s son, Robert Vesey.

At the bond hearing for Dylan Roof family members of some of the victims amazed many by expressing their forgiveness to the killer a gesture in imitation of the words of their crucified Savior.

The thoughts that follow are my attempt to locate their astonishing act of forgiveness in the history of the black church. I will describe precedents over an extended period of African-American religious life stretching back to slavery. In doing so I attempt to demonstrate that African-American Christians adapted from the Bible an alternative religious narrative, or script if you will, contradicting the dominant national myth of America as God’s New Israel or alternately as the Redeemer Nation. In other words they developed a radical criticism of the cultic piety of American exceptionalism. In their narrative Christianity and slavery were incompatible. The earliest printed example of such a critique dates from January 13, 1777, in the form of a Slave Petition for Freedom to the Massachusetts Legislature.

“The Petition of a great number of blacks detained in a state of slavery in the bowels of a free and Christian country humbly show that your petitioners apprehend that they have in common with all other men a natural and unalienable right to that freedom which the great parent of the universe hath bestowed equally on all mankind and which they have never forfeited by any compact or agreement whatever. But they were unjustly dragged by the hand of cruel power from their dearest friends and some of them even torn from the embraces of their tender parents from a populous pleasant and plentiful country and in violation of laws of nature and nature’s God and in defiance of all the tender feelings of humanity, brought here either to be sold like beasts of burden and like them condemned to slavery for life among a people professing the mild religion of Jesus, a people not insensible of the secrets of rational being nor without spirit to resent the unjust endeavors of others to reduce them to a state of bondage and subjection, your honor need not to be informed that a life of slavery like that of your petitioners deprived of every social privilege of everything requisite to render life tolerable is far worse than nonexistence.

“In imitation of the laudable example of the good people of these states your petitioners have long and patiently waited the event of petition after petition by them presented to the legislative body of this state and cannot but with grief reflect that their success hath been but too similar they cannot but express their astonishment that it has never been considered that every principle from which America has acted in the course of their unhappy difficulties with Great Britain pleads stronger than a thousand arguments in favor of your petitioners they, therefore, humbly beseech your honors to give this petition its due weight and consideration and cause an act of the legislature to be passed whereby they may be restored to the enjoyments of that which is the natural right of all men and their children who were born in this land of liberty may not be held as slaves after they arrive at the age of twenty one years so may the inhabitance of this state no longer chargeable with the inconsistency of acting themselves the part which they condemn and oppose in others be prospered in their present glorious struggle for liberty.”

Notice the combination of condemnation of the Christian religious principles of the nation combined with the condemnation of the violation of the civil religious principles of the nation.

This conflict between two versions of Christianity, one that accommodated slavery and the other which did not affected more than legal status. It bifurcated the meaning of the Christian gospel.

The division went deep; it extended to the fundamental interpretation of the Bible. The dichotomy between the faiths of black and white Christians was described by a white Methodist minister who pastored a black congregation in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1862: “Their service was always thronged … the preacher could not complain of any deadly space between himself and his congregation. He was … breast up to his people with no loss of rapport. Though ignorant of it at the time, he remembers now the cause of the enthusiasm under his deliverance about the law of liberty and freedom from Egyptian bondage. What was figurative they interpreted literally. He thought of but one ending of the war; they quite another … It is mortifying now to think that his comprehension was not equal to the African intellect. All he thought about was relief from the servitude of sin and freedom from the bondage of the devil. But they interpreted it literally in the good time coming…”

This preacher learned belatedly that the chasm was wide and deep between his interpretation of Christianity and theirs. As one freed man succinctly put it: “We couldn’t tell no preacher never how we suffer all des long years. He know’d nothin’ ’bout we.”

Moreover, the moral obligations of Christian life in the midst of a thoroughly immoral system created opportunities for slaves to assert their own virtue and personal dignity despite the reigning doctrine of black inferiority and white privilege and superiority. Nancy Ambrose who was the mother of Howard Thurman, a black humanist, mystic, poet and writer used to gather the children in Daytona Beach where Thurman was raised when she noticed that their self-esteem, their self-respect seemed to be threatened and she would tell them the story of an old slave preacher, she was born under slavery, who would preach Sundays on the plantation where she lived. And she said he would preach a long sermon beginning with Genesis and ending with Revelation. By the time he ended he was covered with sweat and tired out. But he’d always pause and look at each one of them in the face and he would say “remember you aren’t slaves, you aren’t niggers, you are children of God.”

In 1855, former slave William Grimes remembered that when his master punished him for something he had not done: “It grieved me very much to be blamed when I was innocent. I knew I had been faithful to him, perfectly so. At this time I was quite serious, and used constantly to pray to my God. I would not lie nor steal … When I considered him accusing me of stealing, when I was so innocent, and had endeavored to make him satisfied by every means in my power, that I was so, but he still persisted in disbelieving me, I then said to myself, if this thing is done in a green tree what must be done in a dry? I forgave my master in my own heart for all this, and prayed to God to forgive him and turn his heart.” Those of you who know the Bible know what passage he was alluding to. “If this thing is done in a green tree [to the innocent] what must be done in a dry [to the guilty]?” That quote aligns him to the sacrifice of Christ and identifies him with the archetypal “suffering Servant”, who spoke these words on his way to death on Calvary: “Daughters of Jerusalem weep not for me, but weep for yourselves, and for your children. For behold, the days are coming in which they shall say, ‘Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bare, and the paps which never gave suck. Then shall they begin to say to the mountains, fall on us and to the hills, cover us. For if they do these things in a green tree, what shall be done in the dry?'” This allusion reveals that it was from his morally superior vantage point that Grimes was able to forgive his master, who lived under threat as he saw it of devastating punishment. Simply put Grime’s view of himself, what it meant for him to forgive his master creates a moral leverage or an act of moral jujitsu if you will, which elevates him over his master. In short, if Jesus came as the suffering servant, who resembled him more, the master or the slave?

A similar attitude was revealed by Solomon Bayley who belonged to the same Methodist class meeting with the man who was attempting to sell Bayley’s wife and infant daughter. Bayley admitted that it was extremely difficult “to keep up true love and unity between him and me, in the sight of God. This was a cause of wrestling in my mind but that scripture abode with me, “He that loveth father or mother, wife or children, more than me, is not worthy of me’ then I saw it became me to hate the sin with all my heart, but still the sinner love; but I should have fainted, if I had not looked to Jesus, the author of my faith…” The attitude which Bayley struggled to achieve in imitation of Jesus seems incredible unless one perceives it as a way of holding onto meaning in the midst of the absurdity of unchecked white supremacy at its worst.

Mary Younger, a fugitive slave who escaped to Canada claimed in an interview “if those slaveholders were to come here, I would treat them well, just to shame them by showing that I had humanity.” The assertion of this humanity despite slavery’s denial is the meaning behind these “difficult sayings” by slaves. The black minister, ecumenist, mystic, and university chaplain, Howard Thurman to whom I just referred, captured the oppositional character of the slave’s Christianity when he claimed in his profound meditation on the spirituals, Deep River, published in 1945 “by some amazing but vastly creative spiritual insight the slave undertook the redemption of a religion that the master had profaned in his midst.” I am going to repeat that because it is a very significant statement. “By some amazing but vastly creative spiritual insight the slave undertook the redemption of a religion that the master has profaned in his midst.” The moral and spiritual dimensions of the slave experience gave rise to a tradition that stood in profound and prophetic challenge to American Christianity. While generations of white American preachers and politicians spoke of America (by which they meant the United States not the Americas) as a New Israel, the Promised Land. African-Americans maintained that on the contrary this nation was the Old Egypt, “Go Down Moses and Tell Old Pharaoh to Let My People Go” and would remain so until all of God’s children were free.

As the late historian Vincent Harding liked to point out it is an abiding and tragic irony that there are two Israels in this country.

Unfortunately when freedom came, it was not complete. The Promised Land still lay off in the distance. On Sunday June 4, 1899, three decades after slavery ended, the Reverend Francis J. Grimke mounted his pulpit to preach the first of a three part series of sermons in the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. On this Sunday, Grimke wanted to calm aroused emotions of dejection and despair at the racial situation in this country, his own dejection and despair as well as that of his congregation. His text that morning was Acts Chapter 7, Verse 57, the stoning of Stephen. “Then they cried out with a loud voice, and stopped their ears, and ran upon him with one accord, and cast him out of the city, and stoned him.” His topic was lynching. Between 1889 and 1899, 1,240 black men and women were lynched in the United States. In 1898 alone, white mobs seized and murdered 104 black people. Accounts of the death of one victim occasioned Grimke’s sermon series. Two months earlier Sam Hose, a black man accused of assault and murder, had been burned alive by a white mob in Newnan, just outside Atlanta, Georgia. According to the newspaper accounts local whites celebrated the atrocity as a festive occasion. Close to 2,000 citizens eager to get to the lynching on time purchased tickets for the short train ride from Atlanta to Newnan. Along the route women on porch steps waived handkerchiefs at the passing cars in celebration of the occasion. This was to be what’s come to be called “a spectacle lynching.” Hundreds arrived too late to watch Hose die, but pressed on to see the charred corpse and to collect some souvenir of the day’s outing. It was April 28, 1899, a Sunday.

Grimke was shocked less by the fact of the lynching than he was by the spectator’s enjoyment of it. How could people who claimed to be Christian go out and do such things? How could the American church “with 155,667 preachers and more than 2 million church members” permit “this awful record of murder and lawlessness?” How could it be that at this late date, a whole generation after slavery, blacks were still “a weak and defenseless race” at the mercy of a “Negro-hating nation?” Race relations on the eve of a new century were worsening, not improving. Disfranchisement eroded the small gains blacks had won during Reconstruction; unprotected by the federal government, southern blacks had no recourse under a system of Jim Crow laws violently enforced by local whites.

Grimke, like generations of black pastors before him, sought to find some meaning, some message of hope in all this misfortune, lest his people despair. “I know that things cannot go on as they are going on now,” he told them. “I place my hope not on government, not on political parties, but on faith in the power of the religion of Jesus Christ to conquer all prejudices, to break down all walls of separation, and to weld together men of all races in one great brotherhood.”

The facts of Grimke’s own life did not support an easy or simplistic belief in Christian progress. He learned at an early age the perversity and intransigence of white supremacy. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, where his mother was a slave, his father was his master. After his father’s death, Grimke’s white half-brother attempted to enslave him despite the provisions of their father’s will that he be set free. At the age of ten Francis Grimke was a runaway slave. Captured several years later, he almost died in the Charleston workhouse where his brother had him jailed as a fugitive. After release, his brother sold him to a Confederate army officer. So no, Grimke did not find it easy to regard whites as his brothers. Even in his own denomination, he had experienced the spirit of caste in overt acts of discrimination. If Christianity were to triumph it would be in spite of the American church, which he castigated in print as “an apostate church, utterly unworthy of the name which it bears.”

Yet Grimke did not despair. He kept faith in the power of Christianity to change the world because other events in his life validated this belief. After the Civil War, he had been assisted north and educated thanks to the generosity of whites. At Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and Princeton Seminary, he had been instructed and respected by white professors. Most surprising of all, he had met and formed close family ties with two of his aunts, his father’s sisters, Sarah and Angelina Grimke, whose antislavery views had forced them to leave Charleston as young women and to achieve antislavery fame in the north for their outspoken and well informed experience based attacks on the evils of slavery. Those of you who know the story of Sarah and Angelina Grimke know that Angelina married Theodore Dwight Weld, one of the major abolitionists of the time and along with him spoke out and preached against the evils of slavery.

From Charleston jail to Princeton Seminary, from betrayed brother to beloved nephew, from slave to prominent cleric, the trajectory of Grimke’s own life countered despair. He was hopeful that the racial situation would, in time, improve but his hope strained in tension with the reality of racism in nation and church. Hope and alienation echoed through his sermon series like a dissonant chord: “Christianity shall one day have sway even in Negro-hating America; the spirit which it inculcates is sure, sooner or later, to prevail. I have myself here and there seen its mighty transforming power. I have seen white men and women under its regenerating influence lose entirely the caste feeling. Jesus Christ is yet to reign in this land. I will not see it, you will not see it, but it is coming all the same. In the growth of Christianity, true, real, genuine Christianity in this land, I see the promise of better things for us as a race.” In reaffirming this belief, Grimke and his congregation were reaffirming the meaning and value of their lives.

Flash forward sixty-four years later on another Sunday morning, September 15, 1963, the congregation of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama was busy preparing for Youth Day, an annual occasion to honor the children of the congregation by giving them roles in conducting the service. Sixteenth Street Baptist had served as the rallying place for the Civil Rights demonstrations that drew national and international attention, thanks to the cattle prods, clubs, fire hoses, and police dogs used by police on demonstrators, many of them children, in the preceding months. It was a hopeful time for the movement. The March on Washington, one month earlier, had mobilized thousands of black and white demonstrators in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. signaling a national up swell of support for desegregation. In Birmingham, protest leaders and city officials had finally signed a desegregation agreement one week earlier. After Sunday school, five adolescent girls stood checking their appearances in front of a mirror in the ladies room in the church basement. One girl was fixing the sash on another’s dress. At 10:22 a.m., a tremendous blast shook the entire church. The bomb was so powerful that the outside brick and stone wall collapsed into the basement. Out of the rubble staggered 12-year-old Sarah Collins, calling the name of her sister Addie Mae. Partially blinded and riddled with 21 pieces of broken glass, she was the only one in the room to survive. Four others, her sister Addie Mae Collins age 14, Carole Roberson age 14, Cynthia Wesley age 14, and the youngest Denise McNair age 11 died. As news of the bombing spread across the nation and around the world, people of all races and nationalities were moved to outrage by the tragedy. Martin Luther King, Jr. later remembered his response: “I shall never forget the grief and bitterness I felt on that terrible September morning. I think of how a woman cried out crunching through broken glass, “My God, we’re not even safe in church!” Prophetic. “My God, we are not even safe in church.” I think of how that explosion blew the face of Jesus Christ from the stained glass window.” What a stunning symbol of the consequence of the bomber’s act. “I can remember thinking, was it all worth it? Was there any hope? Where was God in the middle of these bombs? Our tradition, our faith, our loyalty were taxed that day as we gazed upon the caskets which held the bodies of those children. Some of us could not understand why God permitted death and destruction to come to those who had done no man harm.’ One week later, King attempted to articulate the meaning of the deaths of the four girls as he delivered he funeral oration to the mourning congregation of blacks and whites and to a national television audience as well.

“These children,” he said, “unoffending, innocent and beautiful, are the martyred heroines of a holy crusade for freedom and human dignity. So they have something to say to us in their death. They have something to say to every minister of the gospel who has remained silent behind the safe security of the stained-glass windows. They have something to say to every politician who has fed his constituents the stale bread of hatred and the spoiled meat of racism. They have something to say to every Negro who passively accepts the evil system of segregation and stands on the sidelines in the midst of a mighty struggle for justice. They have something to say to each of us, black and white alike, that we must substitute courage for caution. They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, and the philosophy which produced the murderers. Their death says to us that we must work passionately and unrelentingly to make the American dream a reality. So they did not die in vain. God still has a way of wringing good out of evil. History has proven over and over again that unmerited suffering is redemptive. The innocent blood of these little girls may well serve as the redemptive force that will bring new light to this dark city. So in spite of the darkness of this hour we must not despair. We must not become bitter, nor must we harbor the desire to retaliate with violence. We must not lose faith in our white brothers. Somehow we must believe that the most misguided among them can learn to respect the dignity and worth of all human personality.”

King’s nonviolent philosophy insisted upon agape, an unstinting love that did not permit outward violence or the inner violence of anger, hatred or even resentment and was not conditioned on the goodness of the other. As it so happened, the Sunday school lesson at Sixteenth Street Baptist on that Sunday, the day of the bombing, was “The Love that Forgives.”

Three months earlier in June 1963, Fannie Lou Hamer and seven other Mississippi civil rights organizers attended a five-day workshop on citizenship schools, led by Septima Clark and Bernice Robinson, sponsored by SCLC, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Highlander Research Center and was held on Johns Island near Charleston in South Carolina. Hamer, one of twenty children of a dirt poor share cropping family had already established a reputation for leading attempts to register black voters in Sunflower County, Mississippi, home of Senator John Stennis and had lost her job, her house and almost her life as a result. She had already attended a similar training session led by Clark, Dorothy Cotton, Andrew Young, and Andrew Young’s wife, Jean. Returning home by bus on June 9th, they were stopped and six of their group including Hamer were arrested for trying to be served in the bus depot restaurant in violation of the Public Accommodations Act which the sheriff claimed had not reached Mississippi yet. Hamer and these six others were arrested and jailed in Winona, Mississippi which happened to be the headquarters of the White Citizens Council for the State of Mississippi. Hamer repeated the story of what happened next in interviews in public appearances around the country and significantly on nationwide television during the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Some of you like me are old enough to remember that convention. Where she testified before the credentials committee in a failed attempt to unseat the all-white regular democratic delegation from Mississippi. Those of you who are old enough to remember will remember that Lyndon Johnson was so angered by this that he called an impromptu news conference to get the cameras off of Fannie Lou Hamer. And when the press gathered to see what the conference was about, that he had hastily called, he said it was the seventh month anniversary of the shooting of John Connally in Texas. The journalists as you might imagine looked at one another in bewilderment about what was going on. But Johnson was so angry at this “ignorant woman” as he called her, who was threatening his convention that he wanted to get her off the media. Of course it backfired because all of the national networks showed her testimony in full that evening on the evening news.

This is what she said: “I was placed in a cell, and I began to hear some of the saddest and some of the loudest screams and sounds I’d ever heard in my life. And finally they passed my cell, with June Johnson, fifteen years old. Her clothes was torn off of her waist, and the blood was running from her head down in her bosom, and they put her in a cell. And then I began to hear somebody else when they would scream and I would hear a voice say, ‘Can’t you say ‘yes, sir, nigger? And I understood Miss Annelle Ponder, Southern Christian Leadership Conference worker, I would hear Ms. Annelle Ponder’s voice and she said ‘Yes, I can say “Yes, sir”. So why don’t you say it? And she said ‘I don’t know you well enough.'” Incredible. “And I don’ know how long they beat Ms. Ponder, but I would hear her body when it would hit the floor, and I would just hear the screams, and I will never forget something that Ms. Ponder said during the time that they were beating her. She asked God to have mercy on those people because they didn’t know what they were doing. And finally, they passed my cell, and her clothes were ripped from the shoulder down, one of her eyes looked like blood and her mouth was swollen almost like my hand. I was led out of that cell into another where they had two black prisoners. The state highway patrolman ordered me to lay down on the bunk bed on my face, and he ordered the first prisoner to beat me. The black prisoner said ‘Do you want me to beat this woman with this?’ It was a long leather blackjack with some kind of metal in it, and he, the patrolman, said, “if you don’t beat her you don’t know what we will do to you.’ The first prisoner began to beat me, and he beat me until he was exhausted. I was steady trying to hold my hands behind my back to try to protect myself from some of the terrible blows that I was getting in my back. And after the first prisoner was exhausted, I thought that was all. And the second prisoner began to beat and I couldn’t control the sobs then because I was screaming and couldn’t stop. And during the time the second was beating my dress worked up real high behind my body. And I had never been exposed to five men in one room in my life because one thing my parents taught me when I was a child was dignity and respect. And during the time my dress worked up and I smoothed my dress down, one of the white men pulled my dress up and one of the white men was trying to feel under my clothes. They beat me, they beat me, and I couldn’t hush. And then one of the men walked over and began to beat me in the head. I remember wrapping my face down in the pillow where I could muffle out the sounds. I don’t know how long this lasted, but I remember the same cop was standing there cussing, telling me to get up. At first it didn’t seem like I could get up because at this point my hands was navy blue and I couldn’t even bend my fingers. And he kept telling me to ‘get up bitch. You can walk, get up, fatso!’ They carried me back to my cell and just to bend my knees forward, you could hear me screaming I don’t know how far.” Hamer concluded her testimony to the Democratic Party credentials committee asking a question. “How can these things happen in America? Is this America, the home of the brave and the land of the free?” Flooded with phone calls and telegrams, the committee seriously considered the request to unseat the regular Mississippi Democratic Delegation. Hearing word of this Johnson sent Hubert Humphrey to try to negotiate a compromise. When Humphrey appeared before Hamer and some of the other leaders of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic party delegation, he mentioned that his job as the potential nominee for the party depended on the success of negotiating a settlement. Fannie Lou Hammer looked him in the face and said, “Mr. Humphrey I lost my job for just attempting to vote.” She said, “I’ll be praying for you. I’ll be praying that you do the right thing.” Not only did Humphrey attempt to convince them to compromise, Martin Luther King, Jr. attempted to get them to compromise. And so other black leaders attempted to get them to compromise, patronizing them by saying ‘look you don’t know how the system works.’ And their response was “we didn’t come this far to get two non-voting credentials, we didn’t come this far to not be able to vote on the convention floor.”

Hamer and the other badly injured prisoners were charged with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest and held in jail without medical attention from Sunday to Wednesday. She suffered permanent damage to her kidneys and a blood clot on a nerve in her left eye. During their imprisonment the group tried to sustain their spirits by singing spirituals and freedom songs based by Hamer’s powerful singing voice. Identifying with the persecution of the early Christians, they took solace from apt verses such as “Paul and Silas Bound in jail, Got no one to go their bail, keep your eyes on the prize, hold on.” The wife of the sheriff surreptitiously brought them water and ice and confessed to Hamer that she was trying to lead a good Christian life. Hamer responded to her by recommending that she write down two Bible passages and to read them when she got back to her house. First passage was from Proverbs Chapter 26, Verse 26 and it read “Though his hatred be covered with deception, his wickedness will be exposed in the assembly.” And the second passage was one of her favorites from Acts Chapter 17, Verse 26 “and He made from one blood every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth.” The white woman wrote down the references on a slip of paper but understandably she didn’t return to talk to Hamer about those passages. On Tuesday, the prisoners were hauled before court for a show trial without representation and with some of the very men who beat them acting as jurors they were found guilty of disturbing the peace and resisting arrest. On Wednesday, James Bevel, Andrew Young and Dorothy Cotton, finally got them released on bond. Their joy at being free, however, was quickly dashed by the news that Medgar Evers, the field secretary for the NAACP had just been shot in the back and killed outside his home in Jackson, Mississippi.

Hamer was taken first to a hospital close by in Greenwood and then to Atlanta for more extensive medical care paid for by the SCLC. Then she traveled to Washington, D.C. and New York City, staying away from home for a month. Refusing visits from her family, except for one sister, to shield them from seeing her condition and to recover emotionally from the physical and sexual violence she had endured. By the fall she was back in Mississippi, addressing a Freedom Vote Rally in Greenwood, grounding her rhetoric in the Bible, and Spirituals, and in the preaching style of her and their Black Church background: “The spirit of the Lord is upon me” she began, “because he has anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor. He has sent me to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captive and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty to them who are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord.” Luke Chapter 4, Verse 28 in which Jesus is citing Isaiah Chapter 61, Verse 1. Note that she has appropriated the role of Jesus the prophet appropriating the role of Isaiah, the prophet. The narrative lines of the scriptures both Old Testament and New live on.

I believe that Fannie Lou Hamer, Annelle Ponder, Martin Luther King, Jr., Francis Grimke, Mary Younger, Solomon Bayley and William Grimes would understand and appreciate the acts of forgiveness offered by the families in Charleston.

I’d like to close on a brief autobiographical note, if I may. I was born in 1943 in Bay St Louis, Mississippi, during the period of entrenched segregation and white supremacy. I was born three months after my father was shot and killed by another man, a white man, in Mississippi, in 1943. I grew up without knowing the full story of my father’s death, except that the man who shot him was never prosecuted. My mother and my stepfather decided not to tell me until I was 17 years old and about to begin college, because, as they explained: “We did not want you to grow up hating white people.” At the age of 50, going through a mid-life crisis, I felt that I needed to go back south and to research as a historian the death of my father. The story briefly was that there had been a fight between the manager of an ice house and a black woman from the town who wanted to get two blocks of ice, this was when ice was being rationed during the Second World War, and he wouldn’t give her a second one and they began to fight. And an elderly friend of my family stumbled on the scene and tried to stop the fight and was knocked down. My father heard about this and went to the home of the ice house owner to confront him about the behavior of his employee. He wasn’t home but his wife was there and my father told her that when your husband gets home, I want to talk to him. She told her husband that. And the next day, her husband went to the store where my father was a clerk and took a gun out and shot him to death and left the store telling them “I just killed your nigger.”

Now when I went south, I talked to my relatives many of whom didn’t want to talk about the incident; some of whom did. I went to the police department and I found an arrest record of the man who killed my father. And one of the policemen said I think the son of the man who killed your father lives in Biloxi, not far from Bay St. Louis. So I called him up on the phone, and I said “this is out of the blue, but I wanted to ask you something.” I said, ” your father shot and killed my father and I wonder what story you might have about it?” And he paused and he said “yes, I was nine years old when that happened. I remember it.” And he said “your father, I remember him. He was a big burly man and he and my father fought and he was beating my father up and my father pulled a gun in self-defense and killed him.”

I have a picture of my father standing between my two sisters. One of them was 13 years old, the other one was 11. My father was maybe two inches taller than my 13 year old sister. And I asked my relatives, what did my father look like? They said he looked like you. Your father was slender man. He was not burly. So his story had changed from my family’s story. We agreed that we would sometimes meet. It never happened. I went back to the south several times afterwards, but he was always busy in court so we never met. But it was good to at least talk with him. And I said “what happened to your father?” He said, “my father came down with terminal cancer and shot himself to death.”

I thought about it but didn’t ask him, did he use the same gun as he used to kill my father? The end of that trip, I went to my father’s grave and I had been there many times in the past on visits down south to my relatives. But for the first time I began to cry and then as if in my mind’s eye I saw my father, I saw him up on the ladder in the stockroom and I saw him being shot and I saw him falling. And it was as if he fell into my life. And for the first time a father and a son met and I cried for him, I cried for myself, I cried for my mother and my sisters. And I instinctively knelt down and picked up some grave dust from his grave and rubbed it on my forehead. And then I left.

That is the end of my remarks.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Thank you. Thank you very much. Wow. Will Saletan, you are up first, sir. And then I have Erica after Will, and Emma and Adelle, and Napp, Robert Draper and Karen. Okay. Go ahead Will?

WILL SALETAN, Slate: I’ve been to a lot of these, but I have to say of all the sessions I’ve ever been to this is the one to which the transcript will do the least justice. That was just profoundly moving. Thank you.

I have a question which feels kind of pale by comparison but I’ll ask it anyway. I was really struck by the sense of empowerment that you found in this tradition of forgiveness, in each of these cases. So I guess I want to know about what role forgiveness plays in change. I’ll oversimplify this. On the political right in this country, we hear a lot of “get over it.” Sometimes on the left, particularly in the academy, we hear about “structural obstacles” to change and how difficult if not impossible it is for an individual to transform society given conditions, some of them physical or economic, social, some of them psychological, the mind set of being oppressed. But you spoke of the transforming power of I think at one point of “moral jujitsu.” The key thing is that the oppressed is the initiator. It is almost, I don’t know how to describe it, a radical spiritual act to transport oneself from the position of the oppressed to the person who is capable of forgiveness, who is above. I guess I just want to understand how you think, what role does forgiveness play in that process of change? To what extent can it overcome these structural obstacles? To what extent are those people who say “get over it” right, but perhaps not in the way that they understand it?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: A good question and I’ll stumble around trying to answer it in several ways. Part of what I am referring to here is two scripts, two national myths if you want, two ways of viewing what it means to be — what America means. And what the slaves and their descendants down to the present day have been urging is there is something wrong with the script here. And we have a different script which comes from the same Bible. And we think you ought to pay attention to this other script when you talk about national identity and national purpose. And there have been times, most recently the civil right era, when people were moved to compassion to hear that script, that alternate script, that oppositional script. They were moved by seeing the suffering of black people, whether it was in Selma or Birmingham or Mississippi. And largely that other script became visible because of the press, because of people writing about what they saw of a New York paper that described the screams of people being beaten on the Pettus bridge or even before Selma itself, leading up to it, describe the sounds of black people being beaten in the black belt area around Selma for demonstrating and the demonstration in which Jimmy Lee Jackson was shot to death trying to protect his grandfather. The footage of what happened on the Edmund Pettis Bridge went national. Today we’d say it went viral. And it was ironically shown on television the same day in which Judgment at Nuremberg was being shown as a movie on television. So the press, whether that be broadcast media or printed press, has played a major role in broadcasting, making known to Americans generally the suffering of black Americans.

Now this is important, this may seem like a sidetrack but it is not. I am just about to publish a book with Princeton University Press called Sharing the Divine Pathos: Prophetic Voices in 20th Century United States. And the title comes from the first prophetic voice in the book. There are eight chapters; first person is Abraham Joshua Heschel. Heschel defines the prophet as one who experiences like a fire in the bones the divine pathos for humanity and feels compelled to share it. My argument in the book is that the eight people that I’m dealing with all shared the divine pathos and the premise of the prophetic voice is that people will listen. Indeed prophets tend to shout so loud and to be so in your face that it is hard not to listen. And so this is the mechanism for change. How does somebody answer Hamer’s question? Can this happen? Is this America? So when people saw that on TV and when they flooded the credentials committee with phone calls with — not with emails, but with telegrams, they took that question to heart. How could this happen in America? Once you’ve got people asking how could this happen in America. What can I do about it? Is change possible?

That is the mechanism that you’ve somehow got to get people in touch with what is going on, in terms of oppressing minorities, in terms of the inequality of wealth, in terms of the lousy schools on the Sea Islands outside of Charleston and the ongoing experience of black people with police forces. All of that has to come out with the hopes that Americans will be moved by seeing these things to ask questions. Is this consistent with American’s values, with our values, with my values? Is this consistent with what it means to be a free society? Is this consistent with both the civil gospel and the religious gospel in which we claim to believe?

So that is the way that it works. Now the empowerment is that it is not mandated that it is going to work. The prophets often were persecuted. I mean, I think it was Ezekiel who had to flea for his life from Jezebel. Prophets tend to be folks who get beaten and severely mistreated. But it’s that voice, that alternate script; there is another way of living than the way that we are living now. It doesn’t have to be this way. That is the hope that is kept alive by these examples that I’ve tried to demonstrate to you.

The temptation to despair is always there. But the loss of life feeds, as it were, the decision to go on that you know in their honor we need to go on, we need to persist, we need to keep the struggle going.

I’m not sure if that is a good answer to your question but it is the best I can do.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Will, I bet you have a follow up. But we have a lot of people on the list. Erica is next and then Emma.

ERICA GRIEDER, Texas Monthly: Thank you so much Professor. I was wondering, I have a historical question, and then related to that a ‘today’ question. As a historical matter in the antebellum era were there any theological defenses of slavery in the system, not the slaves rooted in scripture, I mean as opposed to just opportunistic? And then secondly when you were telling the story about Grimes and his reaction to being unjustly punished, his reasoning seemed very straight forward and intuitive to me, so I was wondering how the African-American church has shaped the white church? I mean does it seem so intuitive to me today being raised in a white church because of this tradition?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: On the first question of theological defense, there is huge literature on the pro-slavery versus anti-slavery defenses. And in some ways the pro-slavery defense, theologically, has more textual support than the anti-slavery position. And the slaves faced indoctrination. Charles Colcock Jones, Princeton graduate from Georgia but kind of vaguely uncomfortable about slavery but his wife inherited a whole bunch of slaves so there was no way he was going to be anti-slavery. He couldn’t go back south and be anti-slavery. So what he adopted was a “plantation mission movement.” We’ve got to convert these slaves because the abolitionists in the North are saying our justification for slavery better Christianize the slaves, well we are not Christianizing them. So let’s do it. So he writes catechism for slaves. And he then talks about a slave congregation that he preached to and he was preaching to them about how slaves need to be obedient to your masters, Ephesians, I can’t remember the verses. He says they got up and walked out. And he says as they walked out, they said he is a master, you know he’s got slaves like us or there is no such statement in the Bible or they just left disgusted with his preaching. Nancy Ambrose, the woman who I quoted, Howard Thurman’s grandmother, who I quoted getting the kids together and telling them about her slave preacher, she was illiterate so whenever Howard would read the Bible to her if he’d get to Paul, she’d say I don’t want to hear anything about Paul, don’t read him. So slaves were clear about which sections of the Bible they thought were valid in terms of their experience.

One mistress was talking to her slave one day and she said, Polly how do you keep up your spirits, you know, your life is so hard? Polly said when I heard about Exodus and God’s freeing his people I know it mean we poor Africans because if God will not be good to us someday, why were we born? So this accommodation of the Exodus narrative as being talking about us.

Now this wasn’t just theology in noetic sense, they actually reenacted the Exodus experience in their religious worship in a way of religious dance called the Shout which was quite prevalent on the Sea Islands as a matter of fact off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina.

Counterclockwise dance which has some Methodist backgrounds as well as African backgrounds in which the slaves would clap, counter clap, counter rhythms and shuffle around and on wooden floors you could actually hear the sound of the shuffles, a steady kind of beat. And they would sing snatches of spirituals and hymns over and over again and would lead into kind of a trance in which time and distance disappeared and in which they literally became the Israelites. You know, imaginatively, they became them and became alive in their worship experience. So this wasn’t just an academic debate, it was an experiential thing. They knew in their bodies that these biblical verses talked about them. When King says I’ve been to the mountaintop, Mount Pisgah, and I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the promised land and I know that we as a people, I may not get there with you but I know that we as a people will get to the promised land. He’s referencing a long tradition enacted by his slave forbearers in the plantations of the south. Slaves talk about well we listen to the masters preachers and they say the same thing all the time you know don’t take your master’s hog, don’t take your master’s turkey, be obedient to your masters. When we would want some real preaching, we’d go off into the hush harbors where we would preach over an overturned pot and we would talk about what God really wanted of us. So there is this constant struggle in which the slaves aren’t just passive, they are resisting in very active ways, sometimes at the risk of great punishment. In the hush harbor, it was illegal for them to go off the plantation to another or to hold a meeting on the plantation. There are cases of slaves being beaten and while they are being beaten praying for freedom. Interesting things where masters would say during the Civil War, what are you praying for? They’d say I’m praying for God’s will to be done. No, you mustn’t pray that, you must pray for the victory of the South.

Laughter

So there are all of these forces that can be leveraged which slaves used.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Let me interrupt just to get others in if that is — did we get both of them?

ERICA GRIEDER: We can go to somebody else if you want to get to someone else in and come back to that.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. We will come back to it then. Emma Green.

EMMA GREEN, TheAtlantic.com: Thank you so much for your comments. So a number of evangelical Protestant denominations have gone through a process, you know over a series of decades, but especially recently trying to confront racial tensions that still exist within their church communities. So for example the Southern Baptist Convention had a big meeting on this last spring, the Presbyterian Church in American is going to have one coming up this June, I think. And so I am curious, in those very powerful centers of church life in the United States, are those efforts fraught, is there a way to harness the kind of tradition that you are talking about from within the black church and actually bring that to what is effectively still the white church and denominations that have historical roots in slavery? Then I think moreover, as we are in a time where there is significant racial divide, a lot of hurt, especially around police violence and sort of what’s happening in black communities, urban communities all over the United States. I mean is the white church basically effectively still hobbled by the fact that it is still pretty much divided and hasn’t in a lot of ways reconciled itself with a history that is very much rooted in sort of slavery and racial division?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: I think the answer that I would give to that question is you know everything that can be done needs to be done, but let me frame this in another sense. We still live in a segregated society. Our schools are actually more segregated now than they were even during the civil rights movement. Residential segregation guarantees that. It would be an interesting question to ask you, you don’t have to answer it now, but how many of you have dinner regularly with people of another race? Is there commonality? Now the point that I’m trying to make is that, the issue of how do we desegregate on a micro level, is I think as important an issue and maybe even more important than the larger statements and apologies by denominations. That is fine. But it doesn’t necessarily affect the ongoing racial divide unless people are meeting in schools, in homes, in work places face-to-face and having contact in which their stories can be shared. What we are as a nation is a collection of disparate stories, an ever exfoliating set of separate stories and what we need to bind us together is to be able to hear the stories of others in face-to-face encounter. And that can be sponsored by churches; churches would be a natural place to sponsor that kind of face-to face contact. But it’s amazing when I ask the question of how many of you really meet regularly and experience the life stories of people who come from a different ethnicity than their own. And it is rarer than one might think.

Now Howard Thurman has a lot to say about this in a wonderful book that I would recommend called The Search for Common Ground, in which he argues that the basic thrust of all of life from the simplest cell to the most complex society is community. And that without community, we are unfulfilled but that community especially in a society as diverse as ours can’t be just a community of like. We can’t just see in others our faces. We have to be able to see other faces and people of other stories. And this could be a real function of churches that is to bring people together, not just on Martin Luther King Day but regularly.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Let me get, Professor, a couple of other people in before we take a break. Robert Draper and then Adelle Banks.

ROBERT DRAPER, New York Times Magazine: Thanks Professor. This is really a follow up to Will’s question regarding forgiveness and change. I’d like to get your thoughts on the reaction, the very moved reaction in what I’ll crassly refer to as the white community to the forgiveness that was offered by the families of the Charleston shooting victims particularly when juxtaposed against the reaction in the same community to the Blacks Lives Matter movement going on at the very same time. Not for the first time this sort of duality has taken place throughout the nineteenth century, throughout the Civil Rights Movement, but there has been the observation made that while forgiveness is divine it is not only a poor substitute, arguably no substitute, for justice but that it actually undercuts the emotional locomotion for justice. And so I wonder what your thoughts were about the Black Lives movement going on at the very same time and whether that sort of forgiving spiritual reflex of the families came in any way at the expense of the less forgiving more insistent demand for justice from Black Lives movement?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Yeah, I don’t know the statistics on this or how you would measure it but it would seem to me that the two don’t necessarily need to conflict at all. Indeed that the good will or the amazement of whites and others to their act of forgiveness might lead to an appreciation of that we need to do something about some of these other issues that are roiling the surface, including the Black Lives Matter Movement. I don’t see why they would need to conflict or why the forgiveness of some members, some family members not approved of by other family members, why that act of forgiveness would need to be seen as a distraction from. Indeed the whole televising of the funeral and Obama’s presence there and Obama’s beginning for perhaps the first time to actually address in a very direct way, to actually give a black talk, a black sermon on the racial situation in this country, shows that the two don’t need to be antithetical or one defeats the other. I mean he raised issues of poverty and lack of divergence of education and other major issues in his sermon for Pickney. I don’t see it really as a distraction or it need not be a distraction.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Adelle Banks.

ADELLE BANKS, Religion News Service: Thank you very much for your very moving comments. I actually was going to ask a question that relates to what you were just speaking of and that is the role of the sermon and whether it deals with forgiveness or next steps after these very tragic incidents. And I wondered about your comparison maybe of King speaking after the Sixteenth Street bombing and then Obama after the Emanuel AME bombing, shooting.

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Yeah, again and also going back to Grimke’s sermon after the lynching of Sam Hose. These are all attempts to link the feeling. You know, in Grimke’s case it is the feeling of despair, you know let’s not despair, you know we can’t despair. Even though this is the period that historians call the nadir, the pits, the absolute bottom of race relations in this country. So the sermon is a major way of communicating, of taking these moments of tragedy and communicating them in ways that both arouse pathos and therefore tends to tap into people in terms of activism. In King’s remarks, which come right out of his letter from a Birmingham jail to both white ministers and black ministers, get off your butts and do something about this. And indeed the funerals were the largest grouping ever of white and black ministers together in Birmingham.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. We are about to take a ten to 15 minute break. Karen Tumulty why don’t you get your question in before we take a break.

KAREN TUMULTY, Washington Post: And again can I just add my gratitude and amazement at everything that you’ve said today. I’d like to go back to a point you made early on though, which is that the black theological experience in America was sort of a repudiation of the idea of American exceptionalism which has always had a theological element that God granted this country a special place in human history. But now we see American exceptionalism sort of invoked in our politics constantly. Barak Obama had to spend what two years getting himself out of having suggested that maybe American isn’t that exceptional after all. Is there anyway ultimately of reconciling the black experience with American exceptionalism? Is that ultimately sort of where you go? Or is it just that these are two ideas that can never meet?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: No, I think the force of the oppositional narrative is to point out the flaws in the cultic, dominant, hegemonic, imperial narrative and to say this isn’t the way to go either in terms of civic piety or religious piety. The way to go is all those texts that we’ve been quoting. It is to care for the suffering. It is to help the poor. If you want to make America exceptional, you make it exceptional by how it cares for the least of these. That is how you make it exceptional. If it lives up to John Winthrop’s Charter of Charity, if you actually read Winthrop’s address on the Arabella and King’s Promised Land speech the night before he dies, there is nothing inconsistent there. What Winthrop says is we go into this land to possess it. And the qualities upon our keeping possession of it are caring for one another, community, taking care of the poor, treating each other with love — all the traditional biblical values and yet between those two documents the Charter of Charity speech as it has been called by Winthrop and King’s “I have a dream speech” on the steps of National Monument, the two have not coalesced but there is no reason that they can’t. Basically what that petition was saying, “hey, live up to what you say are your values.” We are enslaved in the bowels of a Christian nation. That is against the gentle religion of Jesus.

Number two is you guys are picking this battle with Great Britain over your freedoms. How can that be consistent with our being enslaved? Samuel Johnson says the worse cries for freedom are from people who are slaveholders. And so look at this inconsistency. You can’t have it both ways. You can become an exceptional nation, you can become the City on the Hill, you can become the new Israel if you live up to these values which you claim are yours.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Well, thank you. Ladies and gentlemen I have about six people on the list but we want to take about a ten minute break. Thank you professor.

Break

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Before we get into Q&A again, Professor Raboteau wanted to make a comment on the previous question.

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Actually, it was a comment on a comment that was made to me while I was having coffee.

The question he asked was what’s your father’s name, which I forgot to mention. My father’s name is my name. His name is Albert Jordy Raboteau. So I’m actually Albert Jordy Raboteau, Jr., or the II, as I prefer, and I have a son who’s name is Albert Jordy Raboteau III, and he has a son, who’s Albert Jordy Raboteau IV. So the line, such as it is, goes on.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. David Rennie, you’re first.

DAVID RENNIE, The Economist: Thank you very much. It’s the first talk I’ve been at that I wish my kids could be here to hear it. So for what that’s worth.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: We’ll invite them next time.

Laughter

DAVID RENNIE: Don’t do that. The question I wanted to ask slightly overlaps with some of my colleagues and it’s about how moral jujitsu and hegemonic, shaming of majority culture, how that works now?

I mean, clearly, in one kind of crude, political sense, Charleston worked because the extraordinary goodness of the Church got flagged down incredibly first. It just moved the logjam. But, in general, are there potential risks to a narrative about how the good response is forgiveness now because in the past, when you had either slavery or legal segregation, it was goodness as a response to a kind of system which denied that it was bad and so there was a kind of shaming– the moral jujitsu worked around shaming in that context. Now the dominant narrative from those who do not wish to hear about Black Lives Matter or black suffering “is that this country was bad.” “Sure, we accept that but now we’re color blind. We want to move on. We don’t want to hear about this anymore.”

So I wanted to ask you, possibly clumsily, how does — does that moral jujitsu work in exactly the same way now in this new context where there’s a risk that people just co-opt it and you say, yes, exactly? You’ve forgiven us because you accept that this was an isolated instant with no larger political significance, you know, that Dylan Roof was insane and their forgiveness has, you know, allowed us to park it. Is there a sense that the moral jujitsu works differently now that the struggle is to deny that the things are normal?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: That’s a very good question and I think my answer to it would go back to something I said at the end before the break. If there could be an opening made by horrendous incidents, like the one in Charleston, for which — you know, frankly, and as a religious person, you know, there is an irrationality to evil.

There is a sense in which there’s something inexplicable about something like that happening and forgiveness isn’t the only — it’s not an adequate answer to something like that. I mean, we’re also thrust back into the book of Job by events that occur, but if what comes out of it is what I referred to earlier as face-to-face talk, communication, that my hope for change lies in communication, and we’re talking about a micro level. Nothing against macro level either, but I think we need to not be strangers to each other and to each other’s experiences and the more that we can become less estranged, the more there’s a possibility of change.

It’s hard to hate somebody who you eat with regularly and it’s important to discover beyond the binary of racism. I mean, for us, what racism means is black and white. Well, racism can mean a lot of other things, too, as we know, as our variety of immigration continues. So there’s always continuing exfoliation of stories from different people from different backgrounds and if we can, on the smaller levels, begin to share those stories and see the suffering and triumph, the sadness, the joy of other people, we can begin to see them. I use some purposely religious language here. We begin to see them not as others but we can begin to see them as icons of God’s presence, as made in the likeness and image of God.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: David has a quick follow-up.

DAVID RENNIE: I wanted to just check if I understood correctly. Are you saying that sometimes the power of what happened in Charleston was that very extraordinary reaction, the whole of American soul actually not just of these other people who are very good, they realized that these people are more American than the killer, that they’re more like us than the killer is? The killer is the alien?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Yes.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Napp Nazworth and then Lauren Green.

NAPP NAZWORTH, Christian Post: You talked about the history and that the split within Christianity, you said, was deep and fundamental and you had two versions of Christianity, some who supported slavery, some who did not support slavery.

Then in response to Emma’s question about what this means for religious institutions, you said what we need to bind us together is to hear the stories of others and face-to-face contact and, we’ve recently seen a trend — we’ve seen a tremendous growth of multiracial/multiethnic churches in the United States and so I wonder what you think about what it means for the future of the Church if we are going to repair that split.

Will the Church become — does the Church need to become more multiracial/multiethnic and, if so, what does this mean for those historically black churches that grew out of the slave churches?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Future questions, I often use the ready excuse that I’m a historian and actually knowing history does not prepare you for knowing the future, but I’ll try to come up with some fuzzy answer to your — it’s a good question.

I mean, one of the questions is for Howard Thurman, who was a major ecumenical figure, who was a chaplain at Howard and was the co-pastor of the first interracial church in the country, the Church for the Unity of All People, founded in San Francisco with a white Presbyterian ministry. He was a black Baptist in background. And the question for Thurman became, well, logically, doesn’t your position mean the disappearance of the black church and he talks about this in a book called Footsteps of the Dream and basically he says, yes, theoretically, but we have a long way to go in terms of something like that happening. It doesn’t necessarily mean the disappearance of the church but the changing of how we think of churches; that is, is there something sacrosanct about denominational lines? Is there something sacrosanct about, for example, as the Church for All Peoples, you have a mixture not just of ethnicities but you actually have a mixture of faiths as an interfaith church, so what some future dimensions may be.

Right now, as far as all of this, as far as I can see as a functional possibility, is for churches to become places where these kinds of discussions, interfaith discussions and interracial and interethnic discussions, can go on, trying to stress basically what the Church believes, which is, at least if it’s Christian, is a universality Christianity.

That’s the answer I would give.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Lauren Green.

LAUREN GREEN, Fox News: I know you’re not a theologian but I think this is sort of a philosophical level. The beginning of your talk, you quoted Scripture, the Lord’s Prayer, which is, you know, forgive us our trespasses, forgive us our debts, forgive us our sins as we forgive others, and I see this sort of as sort of an intellectual level of forgiveness, but then you went on and really explained the reality of forgiveness that is on a visceral level. That’s not intellectual at all. How do you bring these two concepts of forgiveness together?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Yes. The rub of it is the question of how does one take, in this particular case, the Gospel sayings of Jesus. One is how do you pray? So He says, this is how you pray and that results in the Our Father. The crucial part of the Our Father is that particular “forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against others.” That is a prescription of how to live. It’s not just an intellectual formation. It’s a teaching about how you pray but your prayer should be your life. The second quote, which is –

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Matthew 5:43

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Which is, this is the Sermon on the Mount, and this is — He’s saying you — you’ve heard that it was said you shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy. This is the old law. I’m giving you a new law. So the Sermon the Mount is a new 10 Commandments. So this is — again, is not intellectual. This is a Commandment, you know. I’m sorry, folks, but loving your neighbor and hate your enemy isn’t going to work — isn’t going to do it anymore. That’s not sufficient. The new Commandment is if you’re going to be Christians, is you’ve got to love your enemies, etcetera, etcetera, bless those who curse you, you can do good to those who hate you. The last one is in a different category all together, which is, His, that is, Jesus’s enactment of these two Commandments. This is what I’ve said you shall do in your daily prayer and your daily life and this is what I’ve said you’re supposed to do generally. Here’s an example of me doing that. So this is an instruction manual that’s being presented here for living.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Julia, you’re up next.

JULIA IOFFE, New York Times Magazine: Thank you again for your talk. My question is kind of more historical about this dialogue around forgiveness and Christianity to the extent that it was imposed on black people when they were brought over as slaves and, to some extent, used as a tool of enslavement and the kind of — the backlash to Christianity, to this narrative of forgiveness that arose within the black community in the ’60s and ’70s, you know with Stokely Carmichael and the Nation of Islam, and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that and how you see that debate.

ALBERT RABOTEAU: The short answer is that, that debate caused me to go to graduate school at Yale and to write a dissertation on slaves in the book that resulted from that dissertation. It’s called Slave Religion. And the short answer is the last chapter of that book is called Religion, Rebellion, and Docility. And what I basically argue is that rebellion and docility were not the only two alternatives, that there’s another alternative, which involves symbolic resistance to know that you are morally superior, to know that you are not a nigger or a slave but a human being, not just a human being but a child of God, especially when linked to the Evangelical requirement of a conversion experience.

These are people who have experienced God’s total acceptance of them as His children, viscerally have had that experience, and that changes the whole way in which you see life. Let me go on a little bit longer here. Having experienced that, they talk about I felt new, my feet felt new, my hands felt new, I loved everybody and everything. I went out and hugged a tree. Now the thing about that conversion experience is that’s the grammar of faith for white Protestants in the South, as well. One quick note and we can move on.

Slave named Morte is out in the fields and he has a seizure. He has a conversion experience and he gets back to the barn where the owner’s waiting for him and says, “Where were you?” and he tells him his conversion experience. The master begins to cry and he says, “Morte, I see you’re a preacher. I want you to preach before my house on Sunday.” Morte stands up before the big house on a makeshift kind of platform and he preaches to the master and he says I reduced the master and the master’s family to tears and the rest of the people who were around. Now presumably the slaves are watching this. What does it mean to see a fellow slave reducing the master and his family and others to tears by preaching on their enslavement to sin?

JULIA IOFFE: But then, you know, at the end of the day, they’re still slaves.

ALBERT RABOTEAU: That’s right, but it’s not that that’s their only reality. They’re not only slaves. They are children of God with spiritual power and don’t forget Exodus. Their enslavement is not theirs, their children’s is going to end because God intervenes in human history to cast down the mighty and lift up the lowly.

JULIA IOFFE: Thank you.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Carl, you’re up next. Then Elizabeth.

CARL CANNON, RealClearPolitics.com: Professor, I wanted to talk about something you mentioned a couple times and you just were covering there when you said how often, you know, do people have meals with people of a different race on a regular basis and that got me back to thinking about Emmanuel Church in Charleston.

The Sunday after the shootings, the congregants at another church, Citadel Square Baptist Church, came to church there. The names, the nine names that you named were in their program. Those churches are right next to each other. This is a white church and this is a black church. And even before the shooting, the pastors had been talking about doing things. They had never quite gotten around to it with the two congregations and it was 10 years ago that the Southern Baptist Convention issued its Resolution on Racial Reconciliation, acknowledging the Southern Baptist Churches hand in Jim Crow and slavery and its past and said it would do more to support civil rights.

And having those names in the pew there and the people went over from one church, from the white church to the other church and brought flowers. It was a very touching scene. The networks were there. The New York Times wrote about it. There was a guy with a perfect Christian name, Willy Glee, who greeted the white parishioners and said you’ve been good neighbors, and it was a good feeling all the way around. But I’m wondering, hearing you talk, if it’s enough and I would ask if you — it’s a little out of the area but obviously you’ve thought about this. What could these churches do more to actually have real integration and would that help?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: Yes, I mean, and I think what they can do more is basically what the Gospel requires; that is, they could probably do more — I don’t know what they’re doing now. So that’s why I’m saying probably. They could probably do more about schooling in Charleston for poor children. They could possibly do more in their area for the homeless. They could possibly do more in their area for the environment. They could possibly do more — basically, I’ll just say they could do what Pope Francis says.

CARL CANNON: Is there a practical good to having them worship together is what I’m getting at? These two churches are right beside each other and really they’re segregated. There’s no — it’s not like you wrote in your first book. You can go in and get communion at one church. They’ll serve it to you. It’s not like it’s anything but people, they don’t.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Before you answer that question, Maya Rhodan spent a month in Charleston for Time Magazine. Do you want to comment on this point that Carl’s raising? Do you know about this part?

MAYA RHODAN, TIME: I wasn’t there immediately after but when I went down in August, we started by going to Bible Study on a Wednesday and there had become this new Emmanuel, I guess you could say. It’s not necessarily new, it’s just completely different than what it was like, from my understanding, prior to the shooting, because it’s a very diverse group of people, people from the Charleston community who had never worshiped in Emmanuel, people from all over who wanted to just simply pray with the parishioners there because, like you noted before, when people saw this moment of forgiveness, they begun to see people of that church, people of Charleston not as strangers but as, you know, children of God. They saw themselves in the community there and they wanted to pray with them. I think it goes back to this idea of this moment having greater power than we could really understand. It helped people see that though they’d been neighbors all along, they didn’t really know each other and they wanted to better understand and maybe had that happened before, maybe the shooting wouldn’t have happened. I mean, that’s a different topic. It’s just a different way of understanding how to foster communication and understanding within communities. So I don’t know if that answered it at all.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: That’s very helpful. Professor?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: In terms of worshiping together, yes, there are ways of doing that, in terms of having a service on alternate Sundays where you might do that or having a prayer service or having Bible Study in which you have both congregations, you know, welcomed to participate together. I would choose the Bible Study as the first way to go. The first thing I would suggest for them is to have mixed congregation Bible Study.

MICHAEL CROMARTIE: Okay. Elizabeth Dias is next.

ELIZABETH DIAS, TIME: Thank you so much, Professor. As a Princeton Seminary alumni, I know it’s not the university but the seminary, I appreciated you sharing the story of the Grimke family.

I’m curious. You mentioned the two national myths of what America means for the black community and the white community, specifically in churches. I’m curious as a third national myth has really been rising in past decades with the growth of the Latino community just demographically and the different Christian faith tradition that that brings. As a historian, how do you define or describe the Latino history about forgiveness and where do you see that intersect this conversation historically and, I’m just really curious what’s been fruitful about that, what’s been challenging?

ALBERT RABOTEAU: That’s a good question. I have taught courses, not in awhile, but have taught courses on Roman Catholicism in America and the Latino explosion in the population is extremely significant in terms of that. What I would say is that the wedge of Latinos and it comes after some attempts by black Catholics, which is a very small part of the population in Catholicism more among black people, it’s a minority within the minority, comes in the wake of trying to take advantage of what the Catholic Church has adopted as a pastoral policy.