Published March 5, 2021

When complaining about “cancel culture,” conservatives tend to lament its most obvious problem: its aim of censuring, ostracizing, or otherwise punishing people or perspectives that progressives deem unacceptable.

Though many on the left insist that cancel culture is purely an invention of angry right-wingers, examples abound. This calendar year alone, we’ve seen a Disney star fired for a social-media post, a New York Times journalist asked to resign after having responded to a question about a racial slur by invoking the slur itself, and a television host who recused himself from his post after suggesting that, just maybe, we should hesitate before excommunicating from polite society anyone who has attended a gathering with a theme now found objectionable.

In the world of cancel culture, irony is dead.

Over the last few weeks, meanwhile, the issue du jour has been problematic books. Without a word of warning or explanation, Amazon removed from its digital shelves When Harry Became Sally, a sober and scholarly book by Ryan T. Anderson that critiques the Left’s radical approach to sex, gender identity, and sex-reassignment procedures. Despite weeks of complaints, the book remains unavailable, apparently rendered permanently anathema by the world’s largest online bookseller.

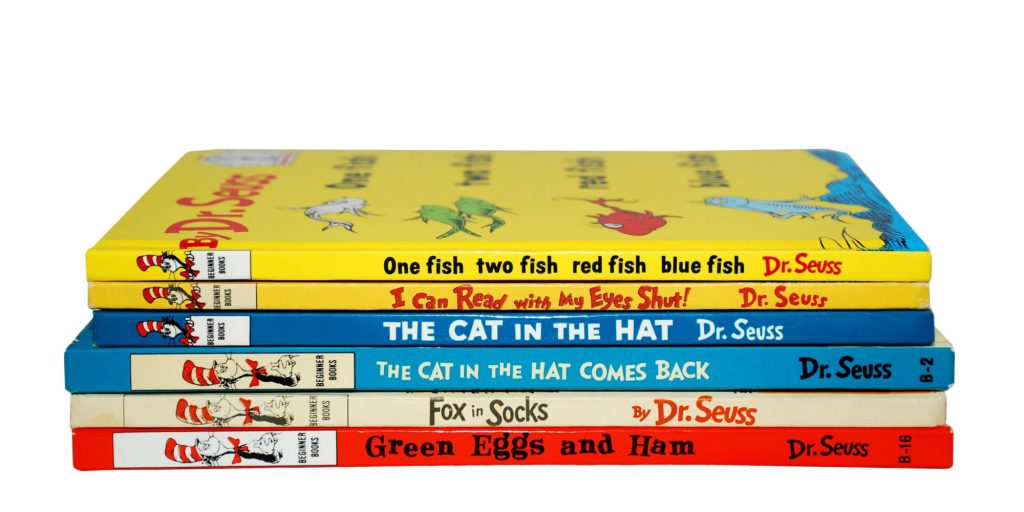

More recently, the debate over unacceptable literature has turned to the work of Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as children’s author Dr. Seuss. In a Virginia school district, several of Seuss’s books were removed from the list for national Read Across America Day, having been deemed inappropriate for children due to alleged racially insensitive content. One library chain announced that a number of Seuss’s titles would remain available but would be relocated from the children’s section to the adult, lest a child stumble across this literary contraband.

It’s troubling enough that those who wield cultural power have such a strong instinct to silence opponents and anathematize views with which they disagree — and that they so often get away with doing so rather forcibly.

But even more concerning is that, at root, this approach demonstrates deep disrespect for human freedom and resilience, as well as for each individual’s ability to choose how he wishes to encounter other views and decide his beliefs for himself.

Cancel culture isn’t just the mentality of bullies and tattle-tales. It’s a mentality adopted by culture-war obsessives who believe it’s their responsibility to protect foolish people from themselves. It’s an outgrowth of the belief that articulating certain views or phrases can cause literal harm — speech redefined as “violence” — and that therefore those views must be silenced for the sake of those who might suffer such harm. This way of thinking can end only in state-policed speech and systematic punishment of wrongthink.

While this attitude tramples on the natural right of every human person to speak freely and defend his views, it also disrespects the freedom and competence of those it seeks to protect.

This mindset seeks, in part, to shield ideological, racial, or other minorities from speech that some find offensive. Though some people within those minority groups might agree with the decision to shut down harmful speech, the impulse to do so demonstrates inherent condescension toward the supposed beneficiaries of such a policy.

This notion treats members of minority groups as if they can’t bear to hear offensive comments or can’t manage to articulate their own competing views unless authorities assist them by removing problematic content from the public square.

Do members of racial minorities, for instance, really need the local library system to step in and remove or re-shelve children’s books so as not to hurt their feelings? Must television stations memory-hole Gone with the Wind and a dozen more movies in case their “backwards” treatment of slavery offends the modern ear?

Perhaps we can trust thinking adults to avoid content they find offensive or troubling — and leave the librarians and television networks out of it.

Meanwhile, as they attempt to protect supposedly victimized groups, purveyors of cancel culture turn their condescension on the rest of us, behaving as though it’s their job to save the rubes around them from falling victim to Bad Ideas.

It is antithetical to human freedom to insist that some wise subset of the elite — or, eventually, the state — must instruct the rest of us in what we ought to read, buy, watch, and say. And yet we increasingly live in a society where a vocal minority erases TV episodes or censures celebrities on the grounds that their wrongspeak might infect the brains of the common individual.

In the end, the most important question is the same one at stake in every debate over how to govern society: Who decides? Which governing body shall we put in charge of determining which jokes or books or TV episodes are too harmful to let people access?

Perhaps we can trust in the capacity of each person to decide for himself what he’ll consume and what he believes — and leave cancel culture’s hall monitors out of it.

Alexandra DeSanctis is a staff writer for National Review and a visiting fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.