Published April 19, 2019

During a Christmas break while I was a student at the University of Washington, I tuned in to a show that influenced the trajectory of my faith, quite by accident. It was a broadcast of an hourlong “Firing Line” interview in 1980 between William F. Buckley Jr. and Malcolm Muggeridge, the British journalist who late in life converted to Christianity.

In the course of the interview, Mr. Muggeridge used a parable. Imagine that the Apostle Paul, after his Damascus Road conversion, starts off on his journey, Mr. Muggeridge said, and consults with an eminent public relations man. “I’ve got this campaign and I want to promote this gospel,” Paul tells this individual, who responds, “Well, you’ve got to have some sort of symbol.” To which Paul would reply: “Well, I have got one. I’ve got this cross.”

“The public relations man would have laughed his head off,” Mr. Muggeridge said, with the P.R. man insisting: “You can’t popularize a thing like that. It’s absolutely mad.”

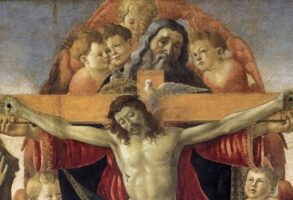

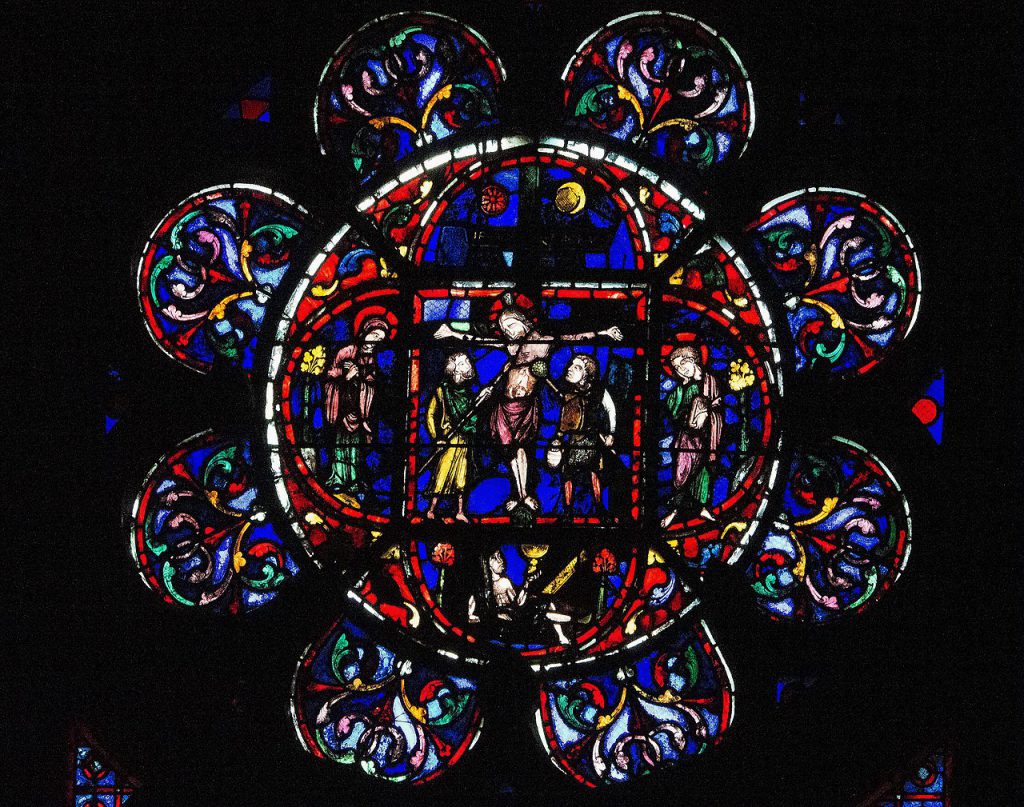

The reaction of Mr. Muggeridge’s imaginary P.R. person is understandable. The Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge has written that until the accounts of Jesus’ death burst upon the Mediterranean world, “no one in the history of human imagination had conceived of such a thing as the worship of a crucified man.” And yet the crucifixion — an emblem of agony and one of the cruelest methods of execution ever practiced — became a historical pivot point and eventually the most compelling symbol of the most popular faith on earth.

As a non-Christian friend of mine put it to me recently, the idea that people would worship a God who is compassionate toward us is one thing, but to worship a God who suffers and dies — as a condemned criminal, no less — is distinct to Christianity. In my friend’s understated words, “When you think about it, it is a little strange.”

Perhaps the aspect of the crucifixion that is easiest to understand is that according to Christian theology, atonement is the means through which human beings — broken, fallen, sinful — are reconciled to God. The ideal needed to be sacrificed for the non-ideal, the worthy for the unworthy.

But the cross is more than simply a gateway to the City of God. “I could never myself believe in God, if it were not for the cross,” John Stott, one of the most important Christian evangelists of the last century, wrote in “The Cross of Christ.” “The only God I believe in is the One Nietzsche ridiculed as ‘God on the cross.’ In the real world of pain, how could one worship a God who was immune to it?” From the perspective of Christianity, one can question why God allows suffering, but one cannot say God doesn’t understand it. He is not remote, indifferent, untouched or unscarred.

Scott Dudley, the senior pastor at Bellevue Presbyterian Church in Bellevue, Wash., and a lifelong friend, pointed out to me that on the cross God was reconciling the world to himself — but God was also, perhaps, reconciling himself to the world. The cross is not only God’s way of saying we are not alone in our suffering, but also that God has entered into our suffering through his own suffering.

Scott readily concedes that there’s no good answer to the question, “Why is there suffering?” Jesus never answers that question, and even if we had the theological answer, it would not ease our burdens in any significant way. What God offers instead is the promise that he is with us in our suffering; that he can bring good out of it (life out of death, forgiveness out of sin); and that one day he will put a stop to it and redeem it. God, Revelation tells us, will make “all things new.” For now, though, we are part of a drama unfolding in a broken world, one in which God chose to become a protagonist.

One other significant consequence the crucifixion had was to “introduce a new plot to history: The victim became a hero by offering himself as a willing victim,” in the words of the Christian author Philip Yancey. Citing the works of the French philosopher René Girard and Mr. Girard’s student Gil Bailie, Mr. Yancey argues that a radiating effect of the cross was to undermine abusive power and injustice; that care for the disenfranchised and those living in the shadows of society came about as a direct result of Jesus’ crucifixion.

Edward Shillito, a minister in England who watched waves of badly wounded soldiers return from World War I, wrote a poem, “Jesus of the Scars,” in which he said, “The heavens frighten us; they are too calm; In all the universe we have no place. Our wounds are hurting us; where is the balm? Lord Jesus, by thy scars we know thy grace.” Mr. Shillito ended his poem with this stanza, which beautifully captures what makes the cross unique:

The other gods were strong; but thou wast weak;

They rode, but thou didst stumble to a throne;

But to our wounds only God’s wounds can speak,

And not a god has wounds, but thou alone.

Worshiping a God of wounds is a little strange, as my friend said. For some, it is grotesque and contemptible, a bizarre myth, an offense. But for others of us, what happened to Jesus on the cross is profoundly moving and life-altering — not just a historical inflection point, but something that won and keeps winning our hearts. As individuals with wounds, flawed and fallen, we cannot help but return to the foot of the cross.

The most important moment in my faith pilgrimage was when the cross became my interpretive prism. What I mean by this is that I was and remain a person with a skeptical mind and countless questions. There are parts of the Bible I still find puzzling, difficult and troubling. (That is true of many more Christians than you might imagine, and of many more Christians than are willing to admit.)

But I did arrive at a settled belief that whatever the answer to those questions were — answers I’m unlikely to ever discover — I would understand them in the context of the cross, where God showed his enduring love for people in every circumstance and in every season of life. I came to treasure a line from an 18th-century hymn by Isaac Watts that I have replayed in my mind more often than I can count: “Did e’re such love and sorrow meet, Or thorns compose so rich a crown?”

In response to his fictional P.R. person’s claim that using the cross as a symbol for faith would be mad, Malcolm Muggeridge replied: “But it wasn’t mad. It worked for centuries and centuries, bringing out all the creativity in people, all the love and disinterestedness in people, this symbol of suffering. And I think that’s the heart of the thing.”

It is the heart of the thing. Where some see the cross as superstitious foolery or a stumbling block, others see grace and sublime love. For us, the glory and joy of Easter Sunday is only made possible by the anguish of Good Friday.

Peter Wehner, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, served in the previous three Republican administrations and is a contributing opinion writer, as well as the author of the forthcoming book, “The Death of Politics: How to Heal Our Frayed Republic After Trump.”