Published April 6, 2017

The New Criterion - March 2017 issue

There’s labor trouble on the rails in Great Britain. Again. And on the Tube and among British Airways cabin crew and baggage handlers at Heathrow. In December, Steve Hedley, assistant general secretary of the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers Union, not-so-affectionately known as RMT, told Russia Today, that, “It’s very clear in our rule book. We’re in an antagonistic relationship with the managers and with the bosses. We want to overthrow capitalism and create a socialist form of society.” Mr Hedley, also known as Red Heds, would have been no more than four years old and so won’t remember, as I do, the dark days and darker nights of the three-day week in 1974 when the Conservative government led by Edward Heath took on the National Union of Mineworkers and lost, but he obviously has something similar in mind.

Back in 1974, the central issue in the February general election campaign was said to be “Who governs Britain?” — the implied alternative answers being the elected government or the trades unions. Though Mr Heath’s Conservative party won the popular vote (as we in America would say), it won fewer Parliamentary seats than Harold Wilson’s Labour party, which therefore formed a new government and gave the miners all they were asking for — though, in the end, neither the overthrow of capitalism nor a quite satisfyingly socialist government. A decade later, after the Conservatives under Margaret Thatcher had returned to power, there was a rematch with the miners which, this time, the Government won. But, to the extreme left apparently, the question of “Who governs Britain” still has not been decided — nor will it be until they can answer: “We do.”

It now seems a lot less likely than it did in 1974 that that day will ever come in a country long accustomed to boasting that “Britons never never never shall be slaves.” Yet even as some of the unions continue to act as if they expected the nation to rally to their cause, they must be dimly aware of how much they are hated by their fellow countrymen. I wish the same could be said of the unofficial power center on this side of the Atlantic with an implicit belief in its own entitlement to rule — by which, as readers will readily apprehend, I refer to the media. Accordingly, in the wake of the election of Donald J. Trump to the presidency, no day has been allowed to pass without our being asked, albeit in subtler fashion than the British were in 1974, who governs the country? This, I take it, is what the presidential adviser Steve Bannon meant when he said that the media, not the Democrats, were now the opposition party.

Writing in The Washington Post (all anti-Trump, all the time), Sanford J. Ungar, distinguished scholar in residence at Georgetown University, recommends that his fellow scribes “eagerly embrace” the description — though “Not the ‘party’ part, of course” — and proceeds irrelevantly to tick off numerous instances in American history in which the press have criticized in the severest terms the sitting presidents of their day. But “the ‘party’ part” is kind of important, isn’t it? It is certainly central to what Mr Bannon (later echoed by Mr Trump himself) was getting at. When the all-but unanimous voice of the media is indistinguishable from that of the ostensible opposition party, on what grounds can the media continue to claim, as Mr Ungar does on their behalf, to be “independent”?

Only, perhaps, in the same sense that they claim independence from the sometimes violent and always obnoxiously anti-democratic demonstrators who depend on them for the sympathetic coverage (as expressions of popular outrage matching their own) they invariably get. Meanwhile, the official opposition in Congress, while engaging in the rhetorical equivalence of riot and affray, trail along timidly behind the media mob, meekly doing their bidding, as the Labour party did that of the trades union bosses in the 1970s. At least the miners had the authority of Karl Marx (such as it was and still is) for thinking themselves entitled to rule by virtue of being the vanguard of the proletariat. For the media, in Britain as in America, the only appeal is to the ever more meretricious idea of the “meritocracy” — in which, of course, the “merit” part is assumed to refer to themselves and those of a like mind in the cognitive elite.

A few years ago I wrote a book called Media Madness which hardly anybody read but in which, if I were minded to boast, I could claim to have foreseen the manic behavior in which the journalistic community has engaged in response to the advent of the Trump presidency. Now Media Madness appears to have reached its acute stage. This new Media Mania should be seen as a sub-species of groupthink, or the tendency of those engaged in a common enterprise to impose on themselves a certain uniformity of opinion which often extends well beyond what is required for the success of the enterprise in question. In the media’s case, however, that enterprise is now, and now openly, the advancement of the progressive agenda, and this is so large a thing that there is almost nothing that cannot be seen as instrumental for its success.

Thus everything that Mr Trump does — everything, ipso facto, that hinders that success — has suddenly become a matter of the utmost urgency. It must be stopped with a new media feeding frenzy of denunciations, assisted wherever possible by noisy street demonstrations, legal action and instructions by the virtual mob on social media (and the actual one outside Chuck Schumer’s home) to the media’s congressional agents to obstruct it.

First (I think, there may have been one or two earlier in the year) there was the dodgy dossier from BuzzFeed and Mr Trump’s news conference blaming the media, especially BuzzFeed and CNN for reporting on the dossier’s existence, if not its content. That spent about a week as the most horrible, heinous thing Trump had ever done before being suddenly ousted by his charge of misreporting the size of the crowd at his Inauguration and the Alternative Fact that his crowd had been bigger than President Obama’s. Then that became the most wicked and unforgivable thing Trump had done. Then, having filed away “alternative facts” for re-use later, he and his media shadows moved on to — well, I forget what the next one was. Voter fraud? The travel “ban”? The “so-called judge”? It’s so hard to keep track, though I remember how definitively awful it was.

But by this time, definitively awful doesn’t seem like much of a story anymore, so often have we heard the same thing before. Mr Trump, in other words, has successfully overloaded the media’s scandal machine once again — as he did during the primary campaign and then the general election campaign — to the point where the thing doesn’t work anymore. And the media don’t seem to know it yet. Instead they keep doing the same thing and expecting a different result — the definition of madness. During the campaign I had my doubts that the future President was clever enough to have worked out how to do this and then to have adopted it as a deliberate strategy. But I’m now beginning to have doubts about my doubts.

In my book, I described Media Madness as a kind of folie de grandeur — a sense of entitlement and self-importance on an industrial scale. But back then, before the election of Barack Obama and except in such politically marginal fora as The New York Review of Books and Hollywood awards ceremonies, it was usually thought politic to keep this megalomaniacal conceit out of sight, as much as possible, while assuming the disguise of mild-mannered reporters for great metropolitan newspapers, or TV networks. Their triumph during the Obama presidency, about which they were as unanimously pro- as they are unanimously anti-Trump, must have emboldened them. Now they do not hesitate to present themselves to the public as the rightful government of the country and in news stories and editorials and opinion pieces alike to cast all the doubt they can on the legitimacy of Mr Trump and all who serve him. “News”, “fact”, “truth” have all become their property, to be decided by them alone, the inhabitants of “the realm of the true” as Jim Rutenberg of The New York Times described it on the day when even some Times readers must still celebrate the birth of the man who described himself as “the way, the truth and the life.”

His bosses at the Times must have been taken with the idea as, with the new year, they proceeded to discharge a blizzard of e-mails seeking new subscribers, all with tag-lines like: “Discover the truth with us” or “Searching out truth is what we do” or “The truth is what we do better” or “We’re passionate about truth. Are you?” When Mr Trump’s adviser Kellyanne Conway incautiously spoke about “alternative facts” in connection with latest media frenzy about comparative crowd sizes at the Trump and Obama inaugurations, they leapt into action with another tag: “Just facts. No alternatives.” The Chicago Tribune and Los Angeles Times got into the act with e-mail solicitations promising to “Tell fact from fiction.”

It all did rather seem, at least to anyone not himself infected with Media Mania, a case of protesting too much. If they have to keep telling us that they are truth-tellers it must be because, at some level, they are acknowledging we might have some reason to doubt it. As, of course, anyone not of their party knows we do. It only confirmed my long-time suspicion about the unwisdom of the tactic when, at the beginning of February, an Emerson College poll was reported to have shown that, after months of shouting about Mr Trump’s “lies,” more people saw him as truthful than saw the media that way. I also believe that more people looked at Ms Conway’s “alternative facts” the way I did than with the jeering spirit of the media. She clearly meant by the expression not fiction but facts that were alternative to the ones that the media were reporting while falsely insisting that there were no alternative facts.

And anyway, isn’t reporting alternative facts what they themselves do every time they announce some new study which overturns all our old assumptions about the world? The great thing about the information revolution, from the media’s point of view, is that suddenly it has produced a whole world of alternative facts to choose from in order to prove anything they like. There’s almost certain to be an alternative fact for that, to be dredged up by the media’s unrivaled trawling operation and presented to readers or watchers or listeners as being true but alternative to common knowledge or common sense. We have their word for it. And if it proves not to be true when someone finds an alternative fact of his own to refute it, who will remember? Who will report it? Who will pay attention if anyone does report it? “The new knowledge,” as Browning prophetically described it a century and a half and more ago, has got to be the property of the progressive left or else it isn’t knowledge.

This boundless confidence in their own righteousness is what lies behind the media’s “Truth”-trumpeting which is, in turn, a form of virtue-signaling, the fashion for which even among otherwise normal people in the age of Trump is, to my mind, the big story of the last month or two. Not that anyone is reporting it. There have always been tiresome sporters of politically correct bumper-stickers, of course, and those who think it will redound to their credit with the people they care about, even if it won’t persuade anyone else, when they put shouty yard signs out at election time. But now it’s not election time any more, and in my neighborhood (one heavily populated by elite types, it must be said) there are a rash of window signs in shops reading, “No vacancy for hate” or “Everyone welcome here.” In shops! they must be very confident that their clientele are all as anti-Trump as they are. As confident as Nordstrom’s (and there went another media wild-goose chase after a Trump tweet).

|

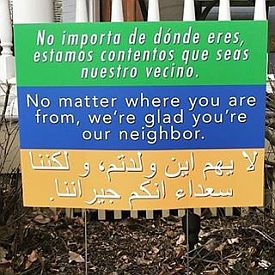

There are even new yard signs. One house in the next block to mine sports a folio-sized notice reading “No matter where you’re from, we’re glad you’re our neighbor” in Spanish, English and Arabic (in that order). That one, clearly, is self-refuting, as its target audience must be those neighbors (like me) they are obviously not glad of and whom they suppose to be in need of such a passive-aggressive anti-Trump rebuke. It is also clear that such gestures of support for the media orthodoxy, even more often encountered on social media than on a stroll around the neighborhood, are not intended to change anyone’s mind but only to advertise the fine feelings of those within, and their membership in good standing of the party of the righteous, the compassionate and the truthful. Not that the “party” part matters, of course.

A couple of years before Media Madness I also wrote a book about honor which could be said to have been prescient, since it was mostly about how we haven’t got any these days. But honor came into existence along with living in society as a way for powerful elites to impose some form of discipline and restraint upon themselves, since there was no one more powerful capable of doing it. When the honor culture broke down during the 20th century — to be replaced by the celebrity culture — so did that discipline and restraint. The media-centered elite and those who seek to join it, having been suddenly and unexpectedly cast into opposition with the election of Donald Trump, illustrate the point by assuming on social media their entitlement by virtue of virtue-signaling to rule.

For if there is anything beneath them in opposing the despised dictator, the hated hegemon, the triumphant Trump, there have been no voices raised, at least not that I have heard, to tell us what it is. Not that we would expect there to be in the post-honor era. The amusing thing is that it is always near the top of the bill of indictment brought against the President by the media and their political hangers on that he is scurrilous and vulgar and willing to say anything derogatory, on every possible occasion, about those who disagree with him or who seek to thwart him. But it’s not Mr Trump who first decided to make gentlemanliness in politics obsolete. He just lives in the world — as now, alas, we all do — where it is. And, whether by brains or instinct, he seems to have been the first Republican after the gentlemanly Bushes to see that and to find a way to turn it to account.

James Bowman is resident scholar at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.