Published September 19, 2016

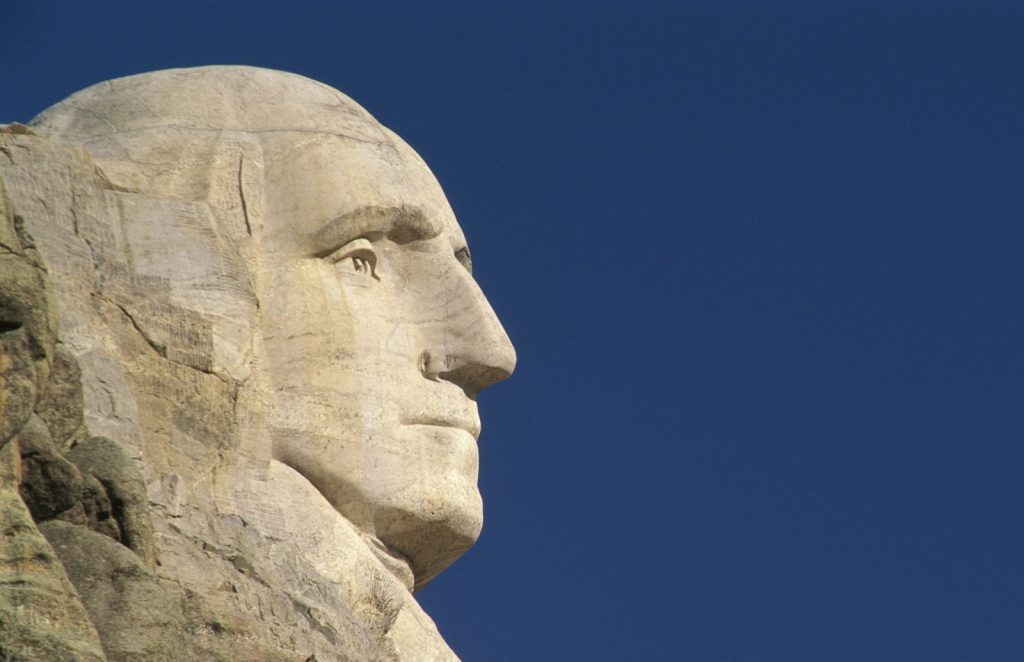

Over on the [National Review Online] homepage, Arthur Milikh has a superb piece commemorating the 220th anniversary of George Washington’s Farewell Address. The Address remains for us an extraordinary store of wisdom and good sense—and a remarkably relevant one this year.

Milikh wonderfully brings out the key strands of Washington’s reflections on the dangers of the spirit of faction and the importance of the moral and religious foundations of American republicanism. And among those I’d highlight two elements of Washington’s Address in particular that might be even more relevant to our peculiar time than the rest. They both have to do with the ways in which our intentionally convoluted constitutional structure, especially if combined with powerful partisanship, can yield great frustration that can threaten the system. We are living in a period defined by a variety of different responses to some very real and powerful political frustrations, and Washington’s cautionary wisdom could hardly be more applicable.

The first danger, Washington warns, can result from the frustration created by the sheer fact of alternating party power, as one group and then another sees itself elevated by the public. This “alternate domination of one faction over another,” Washington argues, “sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension,” distorts republican politics. But it can lead to even worse effects in time:

The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

The frustration of alternating partisanship, which can leave all parties feeling like they are accomplishing little of lasting effect, thus can make some partisans amenable to a strongman who will break the system out of its rut, supposedly in the service of his party’s ambitions but in fact only in the service of his own—if that.

The second danger of frustration, Washington suggests, is that it will inspire a frustrated party to break the bounds of the constitutional system itself in the service of a substantive end held to be more important than the system’s checks on power. He warns:

It is important, likewise, that the habits of thinking in a free country should inspire caution in those entrusted with its administration, to confine themselves within their respective constitutional spheres, avoiding in the exercise of the powers of one department to encroach upon another. The spirit of encroachment tends to consolidate the powers of all the departments in one, and thus to create, whatever the form of government, a real despotism.

Such encroachment, Washington suggests, will surely at first be advanced as serving some positive interest. But that is no excuse:

If, in the opinion of the people, the distribution or modification of the constitutional powers be in any particular wrong, let it be corrected by an amendment in the way which the Constitution designates. But let there be no change by usurpation; for though this, in one instance, may be the instrument of good, it is the customary weapon by which free governments are destroyed. The precedent must always greatly overbalance in permanent evil any partial or transient benefit, which the use can at any time yield.

In both cases, Washington, having served as the first chief executive under the new constitutional system, exhibits a keen awareness of the tendency of the system to induce deep frustration in the champions of various courses of policy. The Constitution is rooted in a healthy fear of the abuse of power and in a sophisticated grasp of the limits of our knowledge and so is designed to frustrate everyone. And such frustration can yield in a sense of false urgency and righteous anger—and in a pressing desire to act beyond the limits placed on action by the Constitution.

These twin dangers—of recourse to an individual who might explode a frustrating status quo and of the encroachment by one branch of government on the powers of the others to break the constraints on swift and forceful action—are by no means only theoretical, or only a thing of the past. In fact, they bear a striking resemblance to the cases made by some (not all, to be sure) of the champions of the two candidates now competing for Washington’s old job.

Let’s hope we always remember the first president’s prudence and wisdom—and not let his successors tempt us away from it.

Yuval Levin is the Hertog Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.