Published October 28, 2020

City Journal - Autumn 2020 issue

I sent an e-mail to a friend in war-torn Minneapolis: “If I were Trump, I would nominate Merrick Garland. Beau geste!”

A few days later, Trump picked Amy Coney Barrett, and I am pleased with the choice—delighted, in fact. But for a moment, the idea of his choosing Merrick Garland amused me for its chivalry. Chivalry has never counted for much in American politics, and certainly not today. But I enjoyed the idea that such a gesture would have a corny, archaic gallantry about it, like Errol Flynn picking up Basil Rathbone’s sword amid all the ferocious snicker-snack and handing it back to him, just at the moment when Flynn should have taken advantage and run the villain through.

Think what a moment it might have been: Trump flabbergasting the world by doing something so eccentrically sporting—so conciliatory, so disarming. The country could use some disarmament. We could use something, anything, that might encourage us to turn off the media stink machine for a moment and to reflect, before it is too late, that until the day before yesterday, this was a more or less functional country, centrist by instinct, whose citizens assumed that they had something in common with one another and that compromise was possible—that it was even a civic duty.

It’s in the nature of the beau geste—a gracious display by someone strong enough not to deal meanly and savagely with people just because he can deal meanly and savagely with them—to yield an advantage to the opponent, out of sheer panache and amplitude, and maybe out of a knightly sense of fairness: noblesse oblige. Noblesse oblige was a motivating ethic of America’s old establishment. It was the voice of the ghost of Endicott Peabody of Groton. (Franklin Roosevelt was a Grottie, you remember: the New Deal came from Groton.) Now, in a country entirely without noblesse—and without an establishment—there remains only the struggle for power—and with it, all the meanness and savagery you may wish.

Politics, dear diary, used to be fun. Elections were fun. What happened?

I count six factors converging:

1) The boomers got old, and they are no fun anymore. This election is their last stand.

2) The young aren’t any fun, either; they have grown fanatical and categorical and self-righteous and—knowing absolutely nothing about the history of terrible ideas—totalitarian-socialistic. Until now, it never occurred to us that it would be so easy to smash up the United States of America.

3) Race obsession has broken out everywhere among elites in media, academe, and corporate life, dividing America between “white supremacists” and black martyrs to 400 years of “systemic racism.” Tertium non datur.

4) A pandemic descended on the world and started killing a lot of people.

5) The economic consequences of the pandemic became dire and unhinging.

6) Donald Trump.

My Minneapolis friend e-mailed back: “This moment is biblical, and each of us is Job.” Is it that bad? Where is wisdom to be found, and where is the place of understanding?

Sometimes, vigorous disagreement stimulates people to think more intelligently. Not this year, when the country’s deep and centrifugal divisions, its blood-feud loathings, have caused Americans in the millions to abandon thinking altogether, even as they have given up on compromise. More and more of us have shut down the possibility that we might change our minds. In 2020, a mind open to the other side’s point of view—a mind capable of truly understanding that point of view—is rare.

In 1988–90, during the first Intifada, I spent months in Israel and Gaza and the West Bank, listening to Palestinians and their life stories, hour after hour, day after day, writing them down in my notebooks. And then, hour after hour, day after day, I listened to Israelis and their stories. I filled a hundred notebooks. And, except for a few lunatics, I understood what people, Israeli or Palestinian, were telling me, and I sympathized with them and with each of the two different universes.

America in the fall of 2020 is beginning to feel like that.

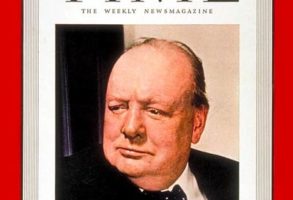

Lance Morrow, a contributing editor of City Journal and the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, was an essayist at Time for many years. His latest book is God and Mammon: Chronicles of American Money.