Published February 10, 2024

Hollywood has lost the plot, and is bricking what should be cinematic layups. The once can’t-miss Marvel franchise is serving up duds. In the hands of Disney, the Star Wars universe is losing whatever fan goodwill and interest it had left. And after a mediocre (at best) debut, Amazon is set to release Season 2 of The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power later this year, and no one really seems to care, let alone be excited about it.

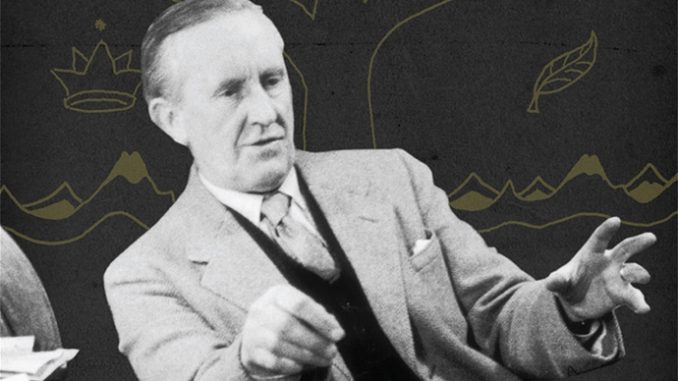

The source material for the last of these franchises provides lessons that the current cultural bunglers could learn from, if they had the humility. Examining how Tolkien wrote and revised his tales reveals why his final results were so much better than Amazon’s. There is special value in seeing how he recognized when he was making a mistake, and how he went about fixing it.

An excellent example of this is seen in the evolution of “The Scouring of the Shire,” a chapter from the end of The Return of the King. This part of the story, which was left out of Peter Jackson’s film adaptation, tells how the hobbits return home and save the Shire from the human brigands who had taken it over. This was a crucial chapter. Tolkien took his time wrapping up all the loose threads of his epic, and“The Scouring of the Shire” not only provides the last action of the story, it largely completes the character arcs of the hobbits, as well as Saruman.

Even though he had long foreseen this part of the story, and foreshadowed it at several points, Tolkien still got it wrong at first. In writing it out, he struggled with both the plot and the characters far more than in the preceding chapters of The Return of the King, including the epic climax of “Mount Doom.” As Christopher Tolkien observed in Sauron Defeated, the volume in which the various drafts were published: “It is very striking that here, virtually at the end of The Lord of the Rings and in an element in the whole that my father had long meditated, the story when he first wrote it down should have been so different from its final form.”

Thanks to Christopher, who as his father’s literary executor organized and published a great deal of additional material, we can see how Tolkien’s work developed from draft to draft. Observing how he revised the story provides valuable lessons in storytelling for today’s scriptwriters, showrunners and directors.

The most obvious of the first draft’s problems were its significant plot issues. Tolkien still had Gandalf with Frodo, Pippin, Sam and Merry when they reached the Shire, but there could be neither drama nor character development for the hobbits if they had the most powerful person in Middle-Earth with them. Tolkien immediately realized this mistake and noted that Gandalf must be left behind.

In contrast, it was not until the second draft that Tolkien realized that it was also a mistake for the returning hobbits to take refuge at Farmer Cotton’s farm, only rousing the Shire after fighting off a band of ruffians. This isolated fight at the farm was not only a tactical blunder by his heroes, it was also a distraction from the hobbits of the Shire standing up for themselves, which, though a small battle, was the final clash of arms of the entire epic.

Tolkien was also initially unclear as to his villain. In the first draft, Saruman had been left dangling as a beggar in the wilderness and Sharkey was no more than a brigand leader, whom Frodo killed in single combat. This illustrates the characterization problems that plagued Tolkien’s first efforts at this chapter: the villain was a meaningless bandit, and Frodo had returned from his ordeals as an energetic warrior and leader, not the wounded, reclusive hobbit who could find no rest or healing in Middle-Earth.

Reintroducing Saruman forced Tolkien to revise his superficial portrayal of Frodo in this chapter. Instead of an eager war-leader, Frodo is restrained. He has learned mercy from his ordeals, and his wounds have given him wisdom. He has grown to a point where he stands above the fallen wizard, who hates him for it. Tolkien undoubtedly liked the image he initially cast of Frodo, facing Sharkey by himself, as “a small gallant figure clad in mithril like an elf-prince.” But it was all wrong, and Tolkien was well-repaid for his willingness to abandon it, for the picture of Frodo as a combatant is not nearly as compelling as that of Frodo showing mercy to Saruman, and the fallen wizard’s bitter acknowledgment of it.

“No, Sam!” said Frodo. “Do not kill him even now. For he had not hurt me. And in any case I do not wish him to be slain in this evil mood. He was great once, of a noble kind that we should not dare to raise our hands against. He is fallen, and his cure is beyond us, but I would still spare him, in the hope that he may find it.”

Saruman rose to his feet and starred at Frodo. There was a strange look in his eyes of mingled wonder and respect and hatred. “You have grown, Halfling,” he said. “Yes, you have grown very much. You are wise and cruel. You have robbed my revenge of sweetness, and now I must go hence in bitterness, in debt to your mercy. I hate it and you!”

That is a far more dramatic scene than Frodo killing a brigand. The encounter ends with the spared Saruman taking his malice out on Wormtongue, who finally turns on him. The contrast with Frodo is clear yet not forced. It is a natural, if unexpected, resolution. Frodo’s mercy had been saved him from his weakness at the end of the quest to destroy the Ring, whereas Saruman is killed because of his persistent spite and cruelty, indulged one time too many.

Tolkien’s revisions took the chapter from an unsatisfying appendage in an extended denouement to an essential and cathartic part of the conclusions. It is not just that we see Saruman get his and the hobbits rising up with Merry, Pippin, and Sam, taking their places as leaders. That is part of it, as is the chapter bringing the reader back to the relatable hobbits we began the story with, away from the lofty style and epic scenes that concluded the main quest.

But even as it does this, there is still loss and wounds that cannot be healed. The Lord of the Rings is not an easy, happily-ever-after tale in which victory is cheap. Indeed, Tolkien wrote so that even the well-deserved death of a villain was a loss, for he had been great and noble once, and might still have been redeemed, had he chosen to be.

Other writers may learn many lessons from observing how Tolkien reworked this material, from the importance of not writing oneself into corners to that of making sure that the obstacles are suited to the stature of the heroes—something that would have been impossible had Tolkien kept Gandalf with the hobbits. They may recognize that themes resonate most when they are supported by the characterization, for consistent and convincing character development is at the heart of great storytelling. And as Tolkien’s abandonment of Frodo fighting the brigand leader in single combat shows, characters must drive images, not the other way around. These are essential skills that would do much to elevate the tales being pushed out by the likes of Amazon, Disney, and Marvel.

But creating true classics requires aspects of Tolkien that modern creators cannot easily emulate: such as his devout Christianity and his rich scholarship, with its immersion in the myths of Northern Europe. Tolkien had a strong faith and culture of his own and was therefore also able to deeply understand and appreciate other cultures. This is far more than can be said of the current enthusiasm for “diversity” and “multiculturalism,” which is often literally only skin deep.

Writing convincing characters requires understanding human (or hobbit) nature. Developing compelling themes requires knowing something compelling. And today’s writers, directors, and showrunners usually have a shallow understanding of human nature and know nothing more compelling than a few buzzwords (diversity! strong female lead!) and a desire to get paid. Thus, having burned through the cultural capital of the past, along with any remaining fan goodwill, they are frantically button-mashing in an attempt to find a winning combo—Geriatric Indiana Jones! Galadriel: Warrior Princess! Marvel Heroes in the Multiverse of Blandness! No wonder audiences are walking away; eventually even the most unquenchable fans lose their enthusiasm for yet another CGI set-piece featuring incoherent characters we don’t care about.

Studying how Tolkien revised his stories can teach many lessons about the mechanics of storytelling. But his full greatness came from knowing what made for a good story, which requires knowing something about the truth of what it is to be human, and what matters in life.

Nathanael Blake, Ph.D. is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His primary research interests are American political theory, Christian political thought, and the intersection of natural law and philosophical hermeneutics. His published scholarship has included work on Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Alasdair MacIntyre, Russell Kirk and J.R.R. Tolkien. He is currently working on a study of Kierkegaard and labor. As a cultural observer and commentator, he is also fascinated at how our secularizing culture develops substitutes for the loss of religious symbols, meaning and order.