Published February 28, 2024

The answer might be buried deep in the Republican convention rules.

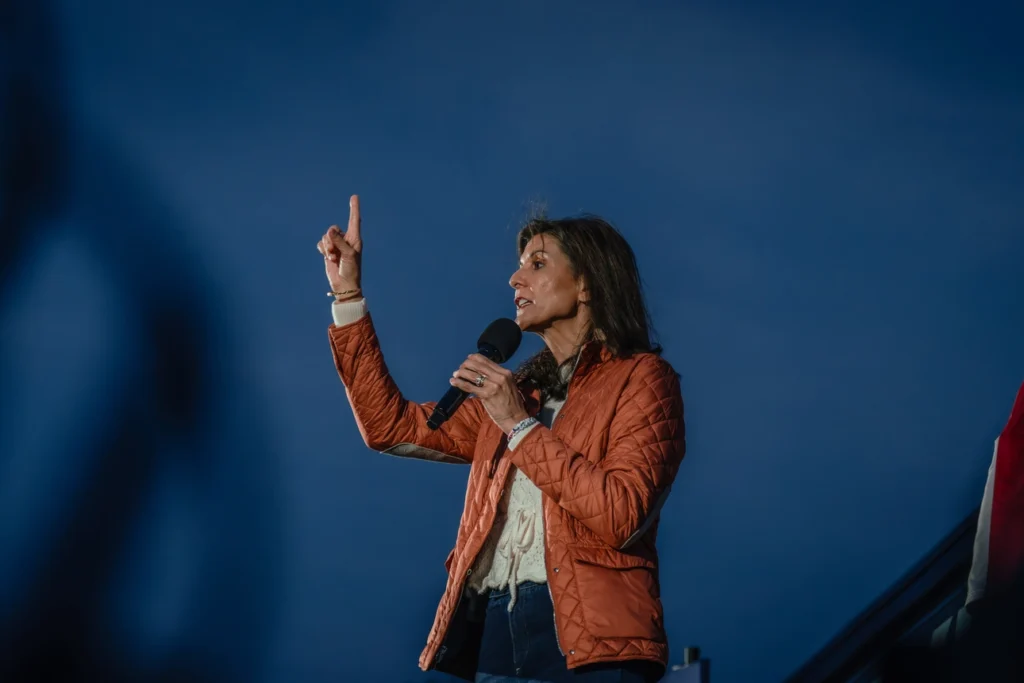

Nikki Haley’s presidential campaign started as an excellent adventure, but it now appears to many Republicans to be a bogus journey. Why is she still in the race after six consecutive stinging defeats?

I have a theory: The answer might be buried in the Republican National Committee’s rules and their potential effect on her voice at the July convention.

Haley will arrive in Milwaukee in possession of a cache of delegates — how many is unclear; at the moment, she has 20.

The rules don’t simply give power to a candidate based on the number of delegates they possess. Candidates cannot have their names placed into nomination, and thereby get television airtime at the convention, unless they have a plurality of delegates in at least five states.

That threshold makes a big difference for Haley in terms of her clout — if any — at the convention. Modern political conventions have morphed into four-day long infomercials for a nominee whose identity has long been known. Every winner wants to use that platform to broadcast a structured, convincing message. Do that right and you can give your candidacy a significant, and perhaps decisive, bounce in the polls.

But that requires ensuring that there are no fights, or alternative messages coming from the convention floor — something winners cannot fully control. Defeated candidates can still deploy their delegates to obstruct the winner’s will by posing contentious amendments to the party platform or by using their nominating speeches to criticize the nominee. That can become news, and prospective nominees will cut deals to prevent that from happening.

Against that backdrop, Haley’s continued campaign makes a great deal of sense. The more delegates she can acquire, the more power she can exert on the floor. And the more power she can exert on the floor, the stronger hand she has to deal from to get concessions from former President Donald Trump on things she cares about, such as U.S. support for NATO. Indeed, given that the party did not even write a platform in 2020, simply insisting that it draft a new one for this election might be a significant request.

Of course, winning at least five states will be hard, owing to her deep weakness with conservative Republicans. She almost certainly can’t win any state where the rules limit the electorate to registered Republicans. She’s also unlikely to win any caucus state because those events tend to draw the most committed — and ideological — party members.

Yet there are a number of states voting on or before Super Tuesday that suit her. How? Haley’s best chances will be in those that are both more moderate than Iowa or South Carolina and that are either open to all registered voters or which permit registered independents to vote in the GOP primary. And they need to have larger shares of college educated voters, Haley’s only consistently strong demographic thus far.

Her travel schedule until Super Tuesday seems perfectly aligned with this strategy. She first held two rallies in Michigan in advance of that state’s primary. She then headed to Minnesota for a Minneapolis event. Both upper Midwestern states are known for their relatively moderate politics and have no party registration, allowing independents and stray Democrats to cast Republican ballots. The fact that Marco Rubio won Minnesota’s 2016 caucuses surely adds credence to Haley’s thought that it might be in play.

Haley jetted to Colorado this week, another moderate state with a high level of educational attainment that allows registered independents to cast Republican ballots. Her rally’s location — Centennial, in the Denver suburbs — speaks volumes about her target audience. Centennial has a median household income of nearly $125,000, according to the Census Bureau, with over 61 percent of adults 25 and older having at least a four-year college degree.

A best case scenario there would be to replicate Joe O’Dea’s nine-point win over a MAGA opponent in the GOP’s 2022 Senate primary. O’Dea won large margins in the Denver metro area and the state’s liberal college and ski counties to drown out his foe’s rural strength.

Then Haley streaks to Utah, which holds a caucus on Super Tuesday. That appears to be a strange choice until one recalls that Mormons strongly opposed Trump in 2016. He finished third in that year’s GOP contest, garnering only 14 percent. He’ll do much better than that this year, but there’s enough lingering discontent among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to give her an outside shot.

After that, she’s back to the East Coast where she holds rallies in North Carolina, Virginia, and the nation’s capital. D.C. is probably her best bet to win because it’s the headquarters of the anti-Trump GOP elite. Rubio and John Kasich combined to get nearly 73 percent here in 2016. If Haley can’t win here, she can’t win anywhere.

Virginia and North Carolina offer more longshot chances at victory. Trump barely beat Ted Cruz in North Carolina’s 2016 contest, with Cruz winning many of the state’s urban areas. Haley’s rallies will be in Charlotte and Raleigh, the state’s two biggest cities that have seen an influx of newcomers, and the fact independents can vote also works to her favor.

The Old Dominion is on the target list for two reasons: there’s no partisan registration and a lot of anti-Trump Republicans. Haley will rally in Richmond and Falls Church, another upper income, high education place that broadly mirrors the broader D.C. suburbs. Marco Rubio handily won metro Richmond and D.C.’s Virginia suburbs in 2016 and nearly carried the state. She clearly hopes Rubio and Kasich voters — and perhaps more than a few non-Republicans — can deliver an upset win.

Her final scheduled events are in especially telling locations. One will unfold in Needham, Massachusetts. Needham makes Centennial look like a slum from the wrong side of the tracks. Its median household income exceeds $200,000 and over 80 percent of adults have a four-year degree or better. Then comes a rally in Vermont, where moderate Phil Scott is one of the few Republican governors to have endorsed her.

Massachusetts, neighboring Vermont and Maine all allow independents to vote in their Super Tuesday contests and typically prefer more moderate Republicans. Haley will be betting they will make a final stand despite the odds against her.

Winning five of these states is a huge stretch, but it’s not impossible. Pull it off and she has the strength she needs to negotiate the terms of her departure with Trump. She won’t get much, but anything tangible gives her something to crow about — and perhaps a springboard for future elections?

Perhaps Haley has no grand strategy, just a desire to keep going and hope for the best. But win or lose, Haley will soon have to end her guerrilla struggle. Whatever her intent, it’s much better for her to exit with a negotiated peace than an unconditional surrender. Soon we’ll see whether she has the leverage to get something from the master of the deal.

Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, studies and provides commentary on American politics. His work focuses on how America’s political order is being upended by populist challenges, from the left and the right. He also studies populism’s impact in other democracies in the developed world.