Published May 24, 2020

There’s something strange about leaving the Morgan Library and Museum’s Old New York study and entering its Thaw Gallery, where an exhibit on the biblical Book of Ruth brings you to a dusty field in Bethlehem. The first line of the Book provides an even starker contrast: “And it happened in the days when the judges judged, that there was a famine in the land, and a man went from Bethlehem in Judah to sojourn in the fields of Moab, he, his wife, and his two sons.” By the third verse, that man, Elimelech, has died. The story of hunger and flight continues; by the fifth verse, his sons have perished as well.

Three widows remain. Naomi, the wife of Elimelech, decides to return to Judah. Her sons’ Moabite wives, neither of whom have children, begin to accompany her, but Naomi insists that they remain. In an anguished moment, Orpah agrees to “return to her people and her gods.” Ruth, however, begs Naomi not to push her away:

Do not wound me by urging me to abandon you, to turn back from following you. Because where you go, I will go, and where you lodge, I will lodge. Your people are my people, and your G-d is my G-d. Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried.

A portion of this speech—“your nation is my nation and your G-d is my G-d”—is featured in the original Hebrew on the cover of the Joanna S. Rose Illuminated Book of Ruth, the centerpiece of the Morgan Library’s “Book of Ruth: Medieval to Modern” exhibit. The words are also paired with the best among New York artist Barbara Wolff’s many superb illustrations: a striking image of an embrace between Ruth and Naomi. The Rose Book includes no faces; Ruth and Naomi are hidden by vividly colored, swirling robes, so that we don’t know which woman is which, or even, almost, where one begins and the other ends. It is a merger of souls and destinies.

The Morgan has been temporarily shuttered due to the coronavirus, but the question the exhibit poses about Ruth remains timely: What does it have to offer a modern audience? To answer this, the Morgan presents the Rose Book—a contemporary work written and illustrated by two Jewish scholars—“in conversation with twelve manuscripts, drawn from the Morgan’s holdings, that unfold the Christian traditions for illustrating the story of Ruth during the Middle Ages.” The Morgan has served as a museum for over 100 years, and this is only the third time it has featured Hebraica. The second instance, in 2015, also featured work by Wolff—an illuminated Passover Haggadah and Psalm 104. All three pieces were commissioned and donated by Joanna S. Rose, who seems to want to elevate Judaic scribal art by blending historical interest with artistic merit. Wolff’s work offers something unique: a combination of medieval artistry, careful scholarship, and the sort of creativity enabled by contemporary technology. Perhaps most striking, there is nothing transgressive in her work; she maintains great respect for the original text and its traditional meaning. The pious attitude of the medieval illuminators is reflected in her own art.

Part of the Rose Book’s message seems baked into its form: 18 feet of accordion-folded pages zigzag through the square gallery, in stark contrast to the medieval works decorously lining the walls. Each side of the manuscript is illustrated in a markedly different style; one contains Hebrew text in gold leaf alongside brightly colored paintings, while the other provides an English translation with black-pen drawings. There’s a never-ending quality to this modernized scroll; it is something more than just a book. And the illustrations often seem to offer a meditation on time.

Following their abrupt fall from grace, Naomi and Ruth eventually make the treacherous journey from Moab to Bethlehem, where they have little to look forward to but more hunger and uncertainty. Naomi is greeted with shock by the Bethlehem locals, who can’t believe she is the same prosperous woman who left Judah a decade ago:

The whole city buzzed with excitement over them. The women said, “Can this be Naomi?”

“Do not call me Naomi [pleasant one],” she replied. “Call me Mara [bitter one], for God has made my lot very bitter. I went away full, and the Lord has brought me back empty. How can you call me Naomi!”

Wolff’s illustration of this scene is subtle, depicting only the transition of a field of wheat from colorful, flowering plants to dry, straw-colored stalks ready to be harvested. Among other things, the image evokes Shavuot, the Jewish holiday on which the Book of Ruth is read publicly. Shavuot also marks the wheat harvest in Israel as well as the day on which the Hebrew Bible was given at Mount Sinai. In this way, Wolff’s painting hints at the unlikely signs of maturation and renewal.

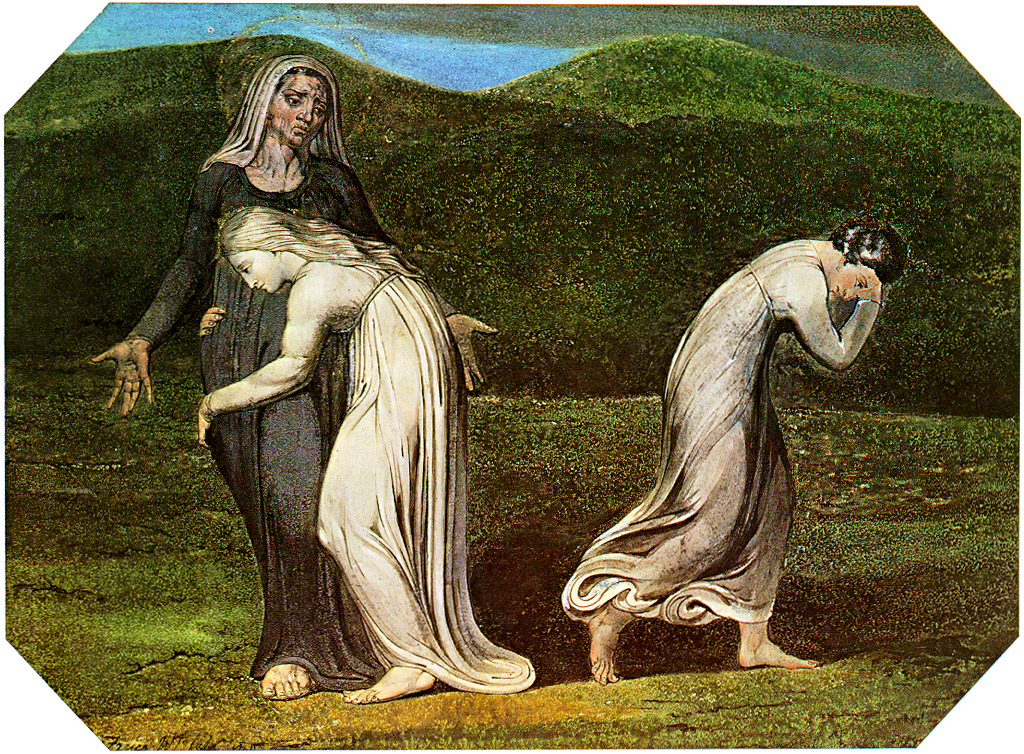

The featured medieval artists, by contrast, are more inclined to emphasize Naomi’s grief and Ruth’s foreignness. For example, the Mirror of Human Salvation, a popular tract from the mid-1400s, presents an image of Naomi mourning her two sons alongside one of Mary mourning Jesus. Two 13th-century Latin manuscripts from France feature Bethlehem locals peering curiously through their windows as Ruth carries grain home for Naomi. The museum’s commentary dwells on these images, noting that “Ruth is now the outsider. Suspicions run high.” It attempts to link Ruth’s journey to modern-day immigration concerns, an appeal that falls rather flat amid global lockdown policies. It also doesn’t reflect the text—Naomi and Ruth were surely impoverished and isolated, but there’s no indication they were treated with suspicion.

Ultimately, Ruth is welcomed by the Judeans. Boaz, a wealthy relative of Naomi’s late husband Elimelech, takes Ruth under his protection, encouraging her to glean exclusively in his fields and warning his workers not to bother her. Privately, he instructs his employees to deliberately scatter extra grain for her to collect. Naomi is heartened by the connection, and helps to arrange a marriage between Ruth and Boaz. They soon have a son, Obed, the grandfather of the messianic figure King David.

Wolff seeks to communicate the reality of Ruth’s life in these moments. Her marriage to Boaz is depicted through an ornate wedding belt based on the festive clothing of Bedouin and Yemenite women; the birth of her son is paired with a painting of a charming pull toy from the early Iron Age (which Wolff discovered in the Israel Museum). Wolff’s painstaking anthropological research is striking in all these drawings, which are often based upon layers of biblical and exegetical scholarship as well.

References to David, for example, appear throughout: in Wolff’s depictions of an ancient harp, a threshing floor modeled after David’s temple, and a sprig of myrtle. The latter is paired with the final few lines of Ruth, which contain a rundown of generations leading up to David. A fragrant evergreen that withstands drought and keeps its color long after it has been cut, myrtle grows wild in Israel and is linked to a number of religious traditions. To Wolff, it evokes “the continuity of life, strength, and vitality. . . . [T]he plant is a potent image of survival and renewal.” Ruth’s connection to David is also underscored by the Christian artists; a leaf from the 12th-century Eadwine Psalter, for example, is largely devoted to an illustrated genealogical tree linking Jesse (the father of David) and Jesus. Similarly, a large, folio-sized Bible from the 13th century concludes its illustrations of the book with the figure of Jesse.

Wolff emphasizes the redemptive arc in Ruth in another way: through a continuous landscape bordering the top of one side of her manuscript. A partial reproduction of the landscape encircles the walls of the gallery, so that viewers can closely follow the journey from famine in Bethlehem to security in the land of Moab and back to the bountiful fields of Judah. The painting ends “with an image of Jerusalem, set on a hilltop amid the forests of the Judean mountains.”

The landscape appears on the colorful “Hebrew side” of the manuscript, which tends to focus on Ruth’s inner life while invoking broader narratives of biblical history. The depiction of an embrace between Naomi and Ruth, described above, appears there. Curiously, none of the medieval manuscripts feature that scene, considered by many to be the heart of Ruth’s story. This seems unnecessary: The moment is beautifully illustrated in the Morgan-owned Crusader Bible from around 1250, for example. But the Morgan chose not to display the folio containing that image.

Wolff’s manuscript also places great emphasis on the relationship between Naomi and Ruth—they are the only two human figures to appear in her work. This is at least in part due to the feminist appeal of their bond; the final page of Wolff’s manuscript is dotted with the names of other women in the Hebrew Bible, from widely admired figures like the matriarchs to lesser-known personalities like Vashti (a somewhat controversial presence in the Book of Esther). While it might be easy to shrug off an attempt to shoehorn Ruth and Naomi’s story into a modern feminist narrative, their connection undeniably guides much of the book. It is the story of both women.

When Ruth has her child, Naomi is the first to be congratulated by the townspeople:

And the women said to Naomi, “Blessed be the LORD, who has not withheld a redeemer from you today! . . . He will renew your life and sustain your old age; for he is born of your daughter-in-law, who loves you and is better to you than seven sons.” Naomi took the child and held it to her bosom. She became its foster mother, and the women neighbors gave him a name, saying, “A son is born to Naomi!”

The story essentially concludes there, proceeding immediately to David’s genealogy. In a sense, the script has been flipped. Where Ruth once insisted to Naomi that “your people are my people,” the Bethlehem neighbors now insist that Ruth’s son is one of their own. Wolff’s image, in which Ruth and Naomi are virtually indistinguishable, seems to encapsulate this idea.

Throughout the manuscript, Wolff provides depictions of plants—dried-out weeds in a wasteland, a sturdy caper bush thriving among stones, palm trees and grapevines weighted down with fruit—to illustrate desolation, hope, abundance. The story that begins with tragedy and ends with the establishment of the Davidic dynasty is, in Wolff’s telling, shot through with reminders of place and the natural progression of time. But more than anything, it hinges on a moment of loyalty—the centerpiece of her work. Wolff’s art and that of the Crusader Bible, among others, serve as a reminder of Ruth’s choice, which echoes through the ages.

Devorah Goldman is a visiting fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a research analyst at the Tikvah Fund.