Published November 9, 2022

In her recent speech for the ISI Gala for Western Civilization, Susan Hanssen observed that today we find ourselves, like Dante at the beginning of the Divine Comedy “in a dark forest” when it comes to patriotism, with the “straightforward path utterly smeared out.” By daring to anchor us to something much bigger and much older than ourselves, patriotism, she observes, has come under sustained attack from “ideologies [that] prey on uprooted and rootless moderns.”

And to be sure, patriotism has fallen on hard times. Still, it has been given something of a lease on life in recent years as a more moderate alternative to the bogeyman of a resurgent nationalism. Faced with the celebration of what they see as an unacceptably exclusive “nationalism,” many liberal thinkers have commended the celebration of “patriotism” in its stead. Patriotism seems more abstract and idealistic, nationalism too uncomfortably blood-and-soil in its overtones. The American patriot, liberal patriotism suggests, can take pride not in exclusive traditions like religion, language, or ethnicity, but in an inclusive commitment to freedom or the glories of our constitutional system, or perhaps to the abstract legal community contained within our current borders.

Etymologically, however, this distinction is hardly compelling. Whereas “national” comes from the Latin root natio, highlighting our allegiance to the people and place that gave us birth, “patriotic” comes from patria, the “fatherland,” emphasizing a blood lineage to our country, or at the very least the necessity of a filial piety to the land that either gave us birth or adopted us. So patriotism is inevitably linked to national character. Hanssen’s speech illustrates the confusion and emptiness that seizes a country when patriotism becomes hollow and unmoored from national specificity; but why has American patriotism gone down this path? What would it take to revive patriotism?

Our loss of piety, which is patriotism’s soul, can help explain our predicament. “Piety” is another word we rarely if ever use in its traditional context, the context not of faith but of family and nation. To the ancients, the pious man was one who recognized the reality of the unchosen bonds of obligation in which we are each embedded, and the duty to render honor and thanks to his ancestors or the institutions and customs they had bequeathed him. As Hanssen notes, such a spirit seems almost unimaginable in our day, in which it is only the chosen, not the given, that seems to command any allegiance, and in which the past is seen as an intolerable burden of guilt, rather than a gift to be gratefully received.

Piety and Gratitude

Patriotism and gratitude, after all, go hand in hand, a truth our Thanksgiving holiday attests but that we rarely pause to consider. We know that Thanksgiving is, somehow or other a national holiday, a time when we celebrate that it’s good to be an American and gesture vaguely toward our earliest founders. And it is a time when, of course, we’re supposed to give thanks for something or other. But what is the connection between these two? Well, if there is anything to give thanks for, it must be first and foremost our very existence—the fact that we were born, that we are still alive, and that we have a place to call home, however imperfectly. And aside from God himself, what have we to thank for this more than our patria?

Such gratitude, however, seems downright offensive in our current cultural climate. Gratitude, today’s deconstructive activists allege, is just an excuse for complacency; it leaves us in smug and arrogant self-satisfaction when we are surrounded by gross injustices that we need to repent and rectify. (Ironically, of course, deconstructionists seem much quicker to repent of someone else’s evils than their own, enjoying a sense of moral superiority over their benighted ancestors and anyone so retrograde as to cherish those ancestors.) Gratitude, they contend, is merely a pious whitewash, and an excuse for inaction.

To be sure, there are times when gratitude for past and present blessings must give way to repentance for past and present errors. Patriotic gratitude can indeed underwrite complacency, and every society needs a few irreverent gadflies prodding it to reform. But can anyone seriously contend that our society has too many self-satisfied patriots and too few angry gadflies at this moment? Can anyone look at a typical university course or elementary school curriculum on American history and complain with a straight face that it celebrates our national heroes too much?

Piety, after all, to return to the central patriotic virtue, need not entail blindness or forgetfulness. The pious man knows the sins and shame of his fathers, but modestly covers their nakedness, like Shem and Japheth, rather than exposing and mocking it, like Ham. This, as we were once catechized, was what it meant to “honor thy father and mother,” a command that encompassed the proper relationship to every kind of authority. In recent years I have frequently been brought back to the arresting words of the Westminster Larger Catechism, with a sheepish sense of my own failures to keep this commandment:

What is the honor that inferiors owe to their superiors?

Answer: The honor which inferiors owe to their superiors is, all due reverence in heart, word, and behavior; prayer and thanksgiving for them; imitation of their virtues and graces . . . bearing with their infirmities, and covering them in love, that so they may be an honor to them and to their government.

Of course, the very language of “inferiors” and “superiors” seems downright absurd to modern ears; and yet, inasmuch as it names a relationship of dependence, who can deny that we find ourselves dependent on and subordinate to our nation, its founders, and those who fought to sustain it over the centuries? In recognizing such dependence, we discover our duty to honor—not by pretending that our nation and the great men and women who forged it have no infirmities, but by refusing to fixate on these faults.

Pious Selectivity

The need for such modest and pious restraint is simple: institutions, however old and venerable (and sometimes oppressive) they may seem, are remarkably fragile things. A little mockery here, a dash of satire there, a bit of “long overdue accountability,” and suddenly we may find social structures that had seemed as solid as stone suddenly passing away as in a dream.

In a key passage of his 2021 book After Nationalism, Sam Goldman discusses Ernst Renan’s pioneering work on nationhood:

“A heroic past with great men and glory,” Renan writes, “is the social capital upon which the national idea rests.” But no nation has a past that is entirely glorious. The record always includes injustice, suffering, and defeat. In order to preserve our accumulated capital, we tend to ignore or minimize these episodes. Renan concludes that not only remembering but also “the act of forgetting” is “an essential factor in the creation of a nation.”

Such selectivity Goldman sees as “dubious.” But why need it be? Every historian knows that selectivity is unavoidable—not merely to reduce material to manageable size, but to cast it into some intelligible form. Every story must leave some things out in order to make sense of what it leaves in. This is all the more true when the stories concern ourselves and those close to us. Consider the role of a eulogy, which is above all an act of filial piety. The eulogist should not lie, to be sure, or indulge in implausible hagiography, but neither does the eulogist dwell on the faults of the deceased. If I believe my grandfather was fundamentally a good man, I will tell his story to my children by highlighting his virtues and his good deeds, rather than his failures or blind spots; I will see his life as a narrative arc disclosing a fundamental identity and core values, rather than an incoherent stumbling between contradictory goals. Is such an account less truthful than a blandly impassive enumeration of sins, successes, and contrasting character traits that fails to paint a real portrait of the man?

The kind of story-telling necessary to sustain any family, community, or nation, though idealistic and over-simplistic, should not resort to cynical fabrication or whitewash, but neither should it even more cynically dedicate itself to turning every imperfect hero into a villain. “For fifty years or more,” Hanssen observes, “we have sustained relentless attacks aimed at destroying the most fundamental bonds of society: the honor due to God, Father, and Country.” No wonder that we are now reaping the whirlwind, however much we continue to admonish each rising generation of the virtues of freedom and tolerance. As any good teacher knows, the repetition of a creed, however inspiring, rarely takes root in a student’s soul. Liturgies and practices are more effective in forming character for the long run, but even these accomplish less than certain recent zealots for the revival of “cultural liturgies” have suggested. What is it that really captures the heart of the young, and gives them a love of virtue and the sense of something worth fighting for? Each young boy or girl, like Bonnie Tyler, is “holding out for a hero”—someone worth emulating, whether for their wisdom, their moral fervor, or their courage. Without heroes to admire, every young soul will wither on the vine. No wonder that, having gleefully deconstructed every would-be American hero for a generation or more, we find ourselves now with a society of desiccated souls, angry and lost.

Capacious Patriotism

Still, what are we to say to the inevitable rejoinder, the fear that such piety and patriotism is just a call to whitewash the past, to bury the iniquities of our forefathers so that we can hide from enduring evils today? This is not an idle worry, and I do not wish to minimize it. The call to “cover the infirmities of our superiors in love,” after all, has been used to justify the grossest abuses in both church and state, and has been a convenient escape hatch to avoid the moral reckoning that God calls us to in every generation. The solution, though, lies not in hiding from our history, but going deeper into it.

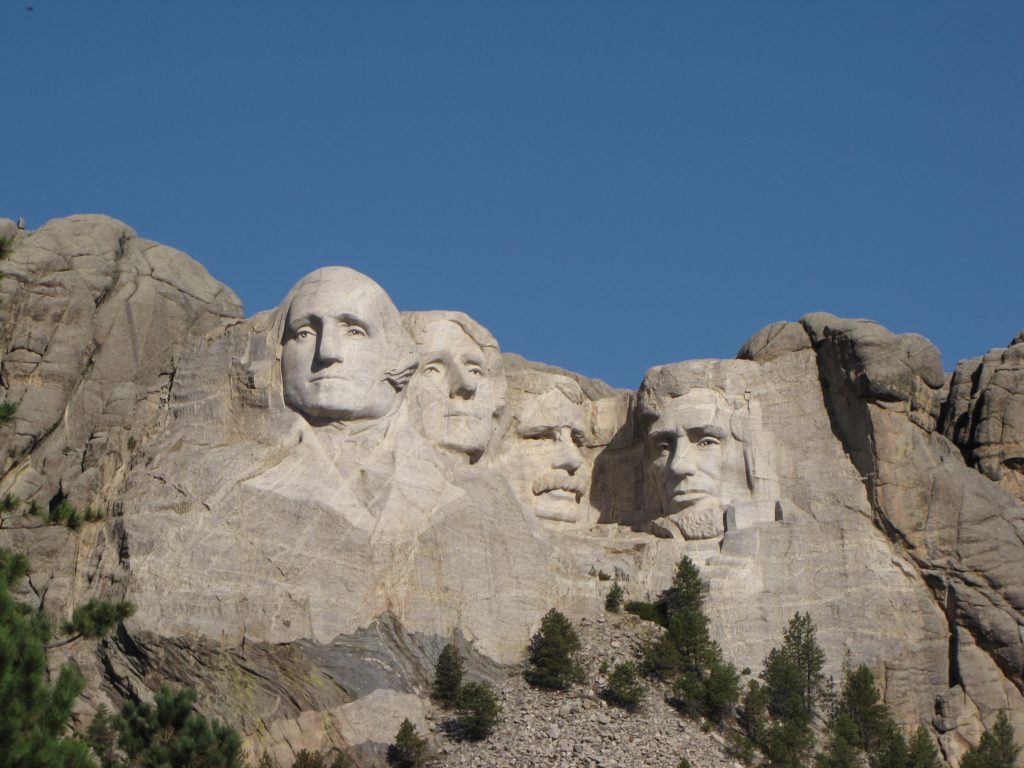

By recovering a richer and broader heritage, we will find ourselves with a pantheon of heroes who do not, it turns out, all speak with one voice, a pantheon of heroes whose very heroism lay in their ability to call one another to account. It is, after all, the mark of the small-minded to conflate goodness with greatness. The truly great man can discern the greatness of another without in any way denying his faults. Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln both belong in the pantheon of American heroes, despite the profound frustration each often felt regarding the other; John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were bitter political foes, but were great enough men to acknowledge one another’s virtues. Indeed, none of the men and women that made our nation great was complacent—anything but! Is there really such a danger that by learning again to honor their stories we will be lulled into moral stupor?

As the American story enters its fifth century, the list of those who have earned the right to be called fathers and mothers of our country grows ever longer. And though conservatives may be tempted sometimes to restrict their piety to a handful of canonical national saints, the true patriot will have the confidence to cultivate a more capacious vision. As we retell our national story to each generation, we will of course continue to argue about whether some of the characters were really heroes or villains—a debate that is part of every nation’s storytelling. But unless we can recover a certain generosity toward those who came before us, we will find ourselves with nothing to pass on to those who come after. Fearing lest the sins of our fathers should be visited on our children, we have committed the monstrous crime of depriving our children of any fathers at all.

In Virgil’s Aeneid, it is precisely by his characteristic piety toward his own father and fatherland that Aeneas displays his love toward those who come after him. As we flee the wreck of Western civilization as he fled the wreck of Troy, may we too remember the importance of remembering—and as we remember, to give thanks.

Brad Littlejohn, Ph.D., is a Fellow in EPPC’s Evangelicals in Civic Life Program, where his work focuses on helping public leaders understand the intellectual and historical foundations of our current breakdown of public trust, social cohesion, and sound governance. His research investigates shifting understandings of the nature of freedom and authority, and how a more full-orbed conception of freedom, rooted in the Christian tradition, can inform policy that respects both the dignity of the individual and the urgency of the common good. He also serves as President of the Davenant Institute.

Brad Littlejohn, Ph.D., is a Fellow in EPPC’s Evangelicals in Civic Life Program, where his work focuses on helping public leaders understand the intellectual and historical foundations of our current breakdown of public trust, social cohesion, and sound governance. His research investigates shifting understandings of the nature of freedom and authority, and how a more full-orbed conception of freedom, rooted in the Christian tradition, can inform policy that respects both the dignity of the individual and the urgency of the common good. He also serves as President of the Davenant Institute.