Published February 7, 2019

Donald Trump’s State of the Union address was a masterpiece—for his purposes. Two chaotic years into his term, Mr. Trump appeared presidential for seemingly the first time and dramatically advanced his chances for re-election in 2020.

I am speaking of perceptions—of how the unusual Mr. Trump plays in the public mind. To call the speech a masterpiece will strike his enemies as preposterous. On the other hand, progressives are sometimes unreliable judges of the country’s moods. Think of November 2016.

On Tuesday Mr. Trump enlarged the public’s idea of himself and his presidency, and in proportion diminished his enemies. That was his most effective stroke on Tuesday night: to make the left seem to be lost in irrelevant obsessions and guilty of misinterpreting—falsifying—America and its values.

He redrew the battleground, leading the discussion abruptly away from progressives’ preoccupations with race and sex. He redefined himself in a more civilized light and sought to lend credibility and bipartisanship to his “Make America Great Again” theme by evoking American history and summoning the better angels. He fetched back to the 20th century’s binary moral perspectives, to the victorious fight against Nazi Germany and to the Cold War against communism.

The speech sought to annul, or at least soften, the left’s radical critique of American history, which has been the theme of elites since the 1960s, and to define Mr. Trump not as a chief of yahoos but a leader of a thoughtful, broadly respectable patriotism. It’s wishful thinking to hope that the speech might help to break the cycle of mutual contempt that has so demoralized the country.

The web has teemed for the past few years with comparisons of Mr. Trump to Hitler, warnings that Trumpism was the start of a new Reich. Mr. Trump installed two Jewish guests in the House gallery—Herman Zeitchik, who went ashore at Normandy in 1944, and Joshua Kaufman, whom Mr. Zeitchik helped liberate from Dachau the following year. The television picture of those two old Jewish men might have come from the epilogue to “Schindler’s List.” Mr. Trump beamed upon them from the podium as if, like Prospero, he had conjured this sweet denouement out of thin air.

The president twice mentioned the mass shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and he proudly took credit for moving the U.S. Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. If Hitler was history’s supreme anti-Semite, Mr. Trump did a fair job of presenting himself as the opposite.

The president played a sly game of trapping his antagonists into applauding when they would have wished to sit on their hands or jeer. The white-clad vestal brigade of new Democratic congresswomen, including that one from Michigan who’d proclaimed her intention to “impeach the m—f—,” were seen turning to one another in confusion and trying to decide whether they would look worse applauding or sitting still.

Mr. Trump manipulated the theatrics inherent in the State of the Union, including the TV cameras’ restless and vigilant reaction shots, to his advantage. As he promised that America would never become a socialist country, the camera focused on the glowering self-described socialist Sen. Bernie Sanders, who looked like a grumpy old man out of Dostoevsky.

Mr. Trump turned things upside down. Portrayed by the left as a lawless president, he insisted on the rule of law, especially regarding immigration. Condemned as a racist, he defused the issue, to a degree, by embracing prisoners’ rights and condemning discrimination in the justice system.

The speech was an eccentric symphony of interwoven themes by which Mr. Trump moved to relegitimize his presidency, associating it with the grand sweep of American history and American values.

He appealed for a closer reading of the country’s terms and conditions, as if to insist that this is not exactly “a nation of immigrants,” and still less a nation of illegal immigrants. It is a nation of citizens who are former aliens or descendants of immigrants—who came to America legally and learned the language of the country, in which the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, Gettysburg Address and Emancipation Proclamation are written. It is a nation of immigrants who have been expected to embrace American civic responsibility as a condition of American freedom.

Metaphysically, the American language is money—the shared idiom, the common denominator, the national theme and genius that overrides all others. Mr. Trump, a man of money, advanced his strongest argument early on in his speech, when he conjured the flourishing state of the economy, a revival (a religious term as well as an economic one) that carries with it the most reliable possibilities of American hope, unity and inclusion. Immigrants are drawn, first of all, by the promise of American money—that is, the freedom to seek it. Freedom and money are the keys to everything.

Mr. Trump said as much. It was his premise. He may be a spectacular oddity in American politics, but he was entirely traditional as he made the essential, paradoxical connection between American money and American virtue—the linkage of opportunity, freedom and possibility.

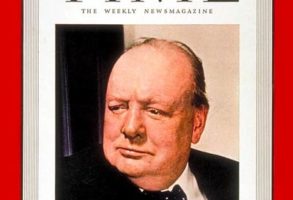

Mr. Morrow, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, is a former essayist for Time.