Published September 27, 2018

The Weekly Standard - October 1, 2018 issue

Who says there is no bipartisanship in the age of Trump? When it comes to federal deficits and debt, the parties have never been more aligned. For most of the last two decades, Republicans insisted they wanted to reform the federal entitlement programs to avert a painful fiscal crunch. In the George W. Bush years, they proposed Social Security reform. In the Obama years, they pushed for changes to Medicare. And all the while, Democrats insisted there was nothing to worry about except Republicans who wanted to deny seniors their benefits—or at least nothing that higher taxes on the wealthy couldn’t solve. But Donald Trump has put an end to the fighting by simply refusing to face the problem altogether, in effect denying that any solution is needed at all. He has taken the Democrats’ denial a step further, and Republicans have been all too willing to follow his lead.

President Trump didn’t create the fiscal mess our country now confronts, of course. But together with Congress, he is well on his way to making it much worse. During the 2016 campaign, Trump paid lip service to cutting deficits by trimming wasteful spending, but he presented no plausible plans for actual restraint. Moreover, he promised voters big tax cuts, no changes to entitlement spending, and a significant reinvestment in the military. With that combination of commitments, he signaled that restraining deficits and debt would not be a priority for his administration.

And sure enough, since his inauguration the government’s fiscal outlook has eroded substantially, mainly due to new legislation championed by Trump and a Republican Congress. The administration has yet to present a realistic budget plan that could reduce future deficits and actually pass, and congressional Republicans have given up any pretense of wanting entitlement reform. The Democrats, of course, only propose to spend more—and increasingly even suggest that the nation’s immense health-entitlement programs should serve as models for aggressive new spending.

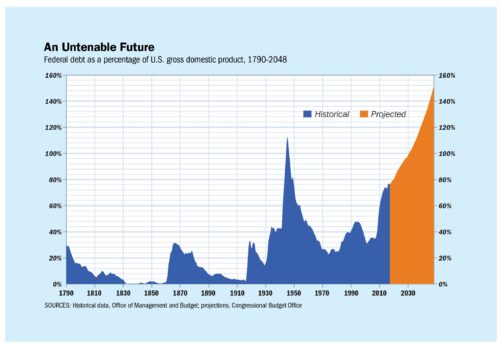

The consequence of this bipartisan determination to borrow and spend is a fiscal outlook that has never been more dire. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the federal government will begin running annual deficits exceeding $1 trillion in 2020 and run a cumulative 10-year deficit of $12.4 trillion from 2019 to 2028. These large deficits are on the order of those racked up immediately after the Great Recession, but they are now in the offing when the economy is strong, employment is high, inflation and interest rates are low, and the business cycle is likely near its peak. If we faced another recession today, we would be starting from a baseline of extremely high deficits and growing them further.

We also confront these projections just as the aging baby-boom generation begins to exert maximum pressure on entitlement spending. CBO projects that under plausible assumptions (such as permanent extension of the 2017 tax cuts), the government’s cumulative debt will grow from 78 percent of GDP this year to 148 percent in 2038 and to 210 percent of GDP in 2048. Debt at such high levels would be unprecedented in the nation’s history (let alone in peacetime), and if CBO’s assumption that we will face no major wars or severe economic crises in this period should prove too rosy, then the debt will only grow higher. In 2008, before the full effects of the financial crash had driven up federal spending and suppressed tax collection, federal debt stood at 39 percent of GDP.

There is a broad consensus among economists that large and persistent deficits slow economic growth by lowering savings and investment. Workers are less productive than they would be otherwise and have lower incomes. In fact, the recent run of stagnant wages is likely owed in part to inadequate investment in productivity growth due to high deficits, and thus low national savings rates, over many years.

Large and persistent deficits also raise somewhat the risk of a genuine economic crisis. It is easy to become complacent about this threat, given the size and strength of the U.S. economy. But there’s no way to predict what would happen if America’s public finances remain on their current course, which is far out of line with historical experience. Countries get into trouble when servicing their debts becomes near-impossible given the size of their governments’ other commitments and the upper limit on revenue imposed by citizens unwilling to tolerate confiscatory tax rates. The United States is likely to have more room for borrowing without facing these most dire consequences, but no one can know for sure just when its luck will run out. Once that invisible line is crossed, interest rates can spike, raising borrowing costs even more, which can quickly spark a serious crisis. It is one of the core responsibilities of public officials to avoid avoidable calamities and to refrain from creating risks of significant harm and disruption for citizens. Our leaders are failing miserably in this regard with respect to federal debt.

Even assuming the United States is fortunate enough to avert a rupture in its ability to readily borrow, the explosive growth of federal spending over the coming three decades will create enormous economic pressure that will lower growth and incomes. The usual justification for borrowing is that it enables investment in the future. But today’s federal budget is heavily biased toward supporting the current consumption of the mostly elderly beneficiaries of government programs, which leaves less and less room for investments in infrastructure or commitments to new basic scientific endeavors that might increase the standard of living of future generations.

The Weekly Standard

All of this is straightforward. Our elected officials all know it. They also know that taking steps to avert the danger will only get more difficult the nearer it is allowed to approach. But the very unpredictability of the consequences of such unprecedented peacetime deficits and debt, combined with a longstanding pattern of failure to think clearly about medium-term risks, has meant that the danger has been permitted to grow.

Politicians have long been in the habit of describing these problems as somewhere off in the distance, so that worrying about them is a matter of not burdening our children and grandchildren. That used to be true, but it isn’t anymore. The 2030s are as close to us now as the 2000s. It’s no longer about our distant descendants. Today’s younger and middle-aged workers will experience the fallout from the unprecedented deficits and debts the CBO projects. And some of the solutions that might have been adequate had we taken them up a decade or two ago will no longer suffice even if we suddenly find the will. Gradual, responsible, politically plausible solutions would need to be started soon. But Washington has proven less and less able to take the problem seriously.

Entitlements Are the Problem

To take the problem seriously would mean, first of all, understanding its causes. Democrats would like Americans to believe that the nation’s fiscal problems stem entirely from a Republican obsession with tax cuts. They are right that reducing federal revenue certainly makes deficits bigger. But tax revenue could never keep up with federal spending on its current course. The real problem is the unrelenting growth of entitlement spending, which has been underway for more than four decades and will continue uninterrupted in the current century if reforms are not put in place.

Historical data and CBO’s long-term projections tell the story. Over the 50-year period between 1968 and 2017, average annual federal tax collections equaled 17.4 percent of GDP. That hasn’t changed. CBO projects that if the 2017 tax cuts are extended, revenue would still be 17.4 percent of GDP in 2028 and 17.9 percent of GDP in 2038. Meanwhile, entitlement spending grew from 5.5 percent of GDP in 1968 to 10.4 percent in 2008. Today, it exceeds 13 percent. CBO projects that federal spending on just Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and Obamacare subsidies will amount to an additional 4.6 percentage points of GDP in 2048, compared with today.

The Trump administration and some Republicans in Congress would like to implement deep cuts in appropriated spending to help ease the budget crunch, but that is as inadequate a plan for fiscal discipline as the Democrats’ dream of balancing the budget by raising taxes on the wealthy. In 2017, discretionary federal spending (defense and nondefense combined) was just 6.3 percent of GDP, down from 7.7 percent in 2008. President Trump’s budget proposes to take that spending down to just 3.9 percent of GDP in 2028, including only 1.5 percent of GDP for nondefense discretionary spending. This is the category of the budget that funds everything from the National Institutes of Health to the FBI and the National Park Service. It is very unlikely that funding for these activities will fall anywhere near as low as the administration’s proposals suggest. And given the many security risks facing the country, it would be irresponsible in the extreme to plan for deep cuts in the nation’s military and national-security programs. But even if such unrealistic proposals could be enacted, growing entitlement spending would still eat up the savings and then some.

The inescapable conclusion from the historical budget data and all plausible projections is that entitlement spending will continue to be the primary cause of the federal government’s fiscal problems. Entitlement spending therefore needs to be the primary focus of any attempted solutions.

Entitlement spending growth is concentrated in three very large programs: Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. And all three are heavily influenced by the nation’s shifting demographic profile. In 1965, when Medicare was created, there were roughly five workers for each beneficiary of that program and of Social Security. Today there are about three, and as the baby boomers rapidly exit the workforce over the coming years the number will continue to decline. This aging of the population also affects Medicaid, as about a fifth of that program’s money is spent on seniors, particularly on long-term care.

For Social Security, this demographic transformation is the essence of the problem. It means that the payroll tax intended to fund the program has proven increasingly insufficient over time. The cost of the program has exceeded its income every year since 2010, but the difference has been made up by income earned from interest on the reserves built up in Social Security’s trust funds in better times. Last year’s report of the Social Security trustees estimated that this interest income would prove insufficient starting in 2022, when the program would have to start drawing on its reserves. But that quickly turned out to be overly optimistic, and in this year’s report the trustees note that the line has already been crossed, four years early. Social Security’s total cost will exceed its total income (including interest income) this year, and if the program is not reformed it will continue to do so every year from now on.

Social Security is living off its reserves, and the trustees expect those reserves to last until 2034. But even if they are right, this does not mean we have that long to address the problem. As former trustee Charles Blahous has noted, if we were to wait until 2034, even denying benefits entirely to newly retiring seniors at that point (which, needless to say, could never happen) would not be enough to enable the program to keep providing benefits to those already getting them. Some reforms must come well before that, and the longer we wait the harder they will be to enact. Social Security’s core old-age and survivor benefit program will spend $834 billion this year, according to CBO, and that number will rise to $1.5 trillion per year by 2028. Reforms will have to take place against the backdrop of enormous fiscal pressures.

Medicare is also an old-age benefit program and so is similarly exposed to the aging of our society, but it has other troubles besides. Medicare has never been fully funded by a payroll tax and has not built up reserves anywhere near those of Social Security. The one portion of Medicare that resembles Social Security’s structure is its hospital-insurance trust fund, which does draw its funding in part from a payroll tax. But that part of the program, just like Social Security, began to draw on its reserves this year, about five years sooner than the program’s trustees expected even a year ago. Its reserves are projected to be depleted well before Social Security’s, in 2026.

The other parts of Medicare (most notably its physician and outpatient services) are already funded largely by general tax revenue, so they don’t face an insolvency date, but they are a massive draw on federal resources and becoming more so all the time. The scope of this spending is underappreciated. Federal taxpayers will be providing an astonishing $4.4 trillion in subsidies for these parts of the program over the next 10 years. More than 15 percent of federal revenue is now spent on Medicare, and that figure is expected to balloon as more and more baby boomers retire—growing much faster than the economy, inflation, or any plausible increase in federal revenue.

This is not entirely because of demographics, of course. Social Security provides age-based cash benefits to a growing elderly population; Medicare provides health insurance, which means its costs are rising both because of a growing base of beneficiaries who live longer and because of health-care costs that have grown significantly faster than inflation for decades. CBO expects net federal spending on Medicare (after subtracting premiums paid by enrollees) to be $590 billion this year and to rise to $1.3 trillion per year over the coming decade.

The fiscal prospects of Medicaid, which provides health coverage to lower-income Americans, are similarly influenced by the rising cost of care and have been transformed over the past decade by a massive expansion of the program under the Affordable Care Act. The ACA increased Medicaid enrollment by nearly 30 percent, to roughly 70 million Americans. The federal portion of Medicaid will cost taxpayers $383 billion this year, according to CBO, and over the coming decade that number is projected to rise to more than $650 billion a year.

But Medicare and Medicaid are not simply victims of rapidly rising health-care costs. They contribute heavily to rising costs through their very design. Medicare in particular is a major reason why American health care is weighed down with rampant waste and inefficiency. It is the primary regulator of the American health-care system. Because it is the biggest payer in the system, its vast and arcane system of rules for paying hospitals, physicians, and other service providers heavily influences how care is delivered to all patients, not just the elderly. Above all, Medicare creates powerful incentives for excess service provision by paying providers on a fee-for-service basis while tightly capping prices per service. That means providers make more by providing more services rather then offering more value, which makes for a less efficient system. Medicare’s administrators have long understood this problem, but attempts to address it have mostly proven counterproductive. Value-driven Medicare reform is therefore essential both to the fiscal health of our government and to keeping health-care costs under control more generally while providing seniors with the care they need and want.

Medicaid is a smaller player in the system but still a massive one, and it also includes incentives that drive up costs. A fundamental problem is the split financial responsibility for the program. The federal government pays for about 60 percent of all state Medicaid spending, with no upper limit. This means states can give their residents a dollar in benefits while spending only about 40 cents themselves, which creates incentives for some kinds of over-spending even as the overall benefit is often inadequate. A web of federal rules imposed on the states has not solved this problem but has made the system even more complex. The sad irony of Medicaid is that its costs are so high that many states are struggling to finance their programs, even as the beneficiaries who rely on the program are too often underserved and provided with an unacceptably low quality of care.

In both cases, we find the federal government worsening the problem of rising health-care costs and then paying a heavy price for it. Health-entitlement reform is therefore imperative both for fiscal reasons and to enable the American health-care system to provide more people with access to affordable coverage and care.

All three of our major federal entitlements cry out for reform. Without it, a painful fiscal crunch will grow increasingly unavoidable. That doesn’t make the politics of improving these programs any more palatable. But it means there is no excuse for avoiding the problem or for exaggerating the difficulties involved in addressing it.

Paths Toward Reform

The debate over entitlement reform suffers from two kinds of hyperbole. Opponents of change, generally on the left, often charge that any modification to the benefit rules of the major entitlements would be the first step toward their elimination. But some proponents of reform, especially on the right, reinforce these scare tactics by claiming that their ideas will lead to a wholesale remaking of these programs (if not of American government more generally), when in fact realistic proposals would make gradual changes in incremental ways.

The truth is that the nation has built a vast and expensive social safety net supporting the income and health of retirees, and the goals of this safety net are deeply established on all sides of our political culture. They are not going anywhere. What is being debated is how to modify and adjust the entitlement system to ensure it continues to provide the protection taxpayers expect while being affordable and consistent with the economic dynamism and growth that pay for it. The challenge, which is a core challenge facing every liberal society, is how to balance dynamism, security, and social cohesion.

The focus of reform must necessarily be budgetary in part, to reduce the fiscal risks in the paths these programs are on today. But reform should also make the programs work better for the beneficiaries who rely on them. In each case, reform would have to begin by distinguishing means from ends and thinking about how to achieve the purpose of the program rather than how to preserve its current design.

Social Security serves two primary purposes. First, the program requires all workers to set aside a portion of their pay during their working years in return for its partially meeting their retirement-income needs when they grow older. In a modern and wealthy country, citizens do not want the elderly to live without sufficient means when they are no longer able to provide for themselves through their own earnings. Many people will set aside sufficient reserves to finance their own retirements, but some won’t, which means some workers will be asked to pay for the retirements of others as well as for themselves. To minimize this burden, Social Security compels all workers to participate in a system that provides a minimum level of retirement support. It’s a pay-as-you-go system, so the money isn’t actually invested and set aside until a worker retires. Instead it is used to pay for the benefits of current retirees, and the worker earns credits that he will draw on when he retires.

The second purpose of Social Security is to provide additional financial support in retirement to workers who earn low wages in their working years and are therefore unable to save enough for their retirements. The program’s benefit rules are weighted to provide a greater replacement rate for low wages than for high wages, which has the effect of boosting the retirement incomes of workers with low lifetime earnings.

Combining these two purposes with other social benefits (such as assistance for spouses, survivors, and dependent children) has made the current program impossibly opaque to workers. Very few Americans understand the rules sufficiently to know what to expect from the system when they retire.

Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute has developed a reform plan for Social Security that would better serve the two purposes of the current program, and in a way that is both more progressive and more supportive of work. He would address the two purposes by creating two distinct elements of Social Security. The first would provide a universal, flat retirement-income payment to all eligible retirees. This benefit would be tied to the poverty line and ensure that all retirees who contribute sufficiently into Social Security would be guaranteed an income that is at least equal to the poverty line. This provision would raise the benefits of approximately one-third of all Social Security beneficiaries who today get benefits that are below the measure of poverty—and by so doing it would put an end to poverty among retirees. In this way, the reform would be more progressive than current law.

The second part of Social Security would be a fully funded, earnings-related savings program, financed by the remainder of the payroll tax not needed to finance the universal flat benefit. All workers would set aside a portion of each paycheck in a personal savings account that would help finance their retirements. The more a worker earns, the more he would set aside in his retirement account.

Redesigning Social Security in this manner would allow for the elimination of several current rules that penalize work. The universal flat benefit would be available to all retirees above a certain eligibility age (based on the expected lifespans of beneficiaries). Past that age, workers would no longer be required to pay the payroll tax or be penalized with lower benefits if they continue to work. In fact, the more they work, the greater their benefit because they would continue to contribute to the second, earnings-related portion of the program.

This kind of reform, designed to take effect gradually and without creating major disruptions for older workers and retirees, would better align Social Security with the needs and dynamics of the modern economy and result in a program better suited to meeting its original goals while avoiding fiscal ruin, helping the neediest most, and encouraging growth.

Medicare also has two basic purposes, so a sensible reform of Medicare would be analogous in some ways to the one proposed for Social Security, but for slightly different reasons.

Medicare’s first goal is to provide a guaranteed insurance benefit for all retirees 65 and older at a premium that does not vary based on the health status of the beneficiary. This is a highly valued benefit of Medicare because in a fully deregulated private market retirees in poor health would find it hard—maybe impossible—to get insurance at an affordable premium. Older people are in poorer health as a general matter, so Medicare serves an important purpose (and even makes possible a competitive insurance market for younger Americans) by giving the elderly access to guaranteed coverage.

The second purpose of Medicare is redistribution from current taxpayers to retirees. Medicare beneficiaries pay premiums for their enrollment into coverage for physician services and outpatient prescription drugs, but these premiums cover only a small part of overall program costs. The very large balance is paid from the general fund of the Treasury, meaning it effectively comes out of income-tax payments from individuals and corporations.

Medicare reform should separate these purposes, to allow for better targeting of financial support to those beneficiaries who truly need the most assistance and to bring greater market discipline to the provision of medical services.

In a redesigned program, everyone who reaches the age of eligibility (also calibrated to reflect lifespans) would be eligible for enrollment in Medicare at the same premium. In addition, like Social Security, Medicare would provide a universal premium-support payment to all beneficiaries, financed from the payroll taxes individuals pay during their working years. This universal benefit would finance only a portion of the total premium. Workers who have sufficient lifetime earnings would be expected to pay the balance of the premiums out of their retirement incomes and savings. Workers with lower lifetime wages would get additional subsidies beyond the base level of support. As with the Social Security reform described above, the idea would be to provide a base benefit to all and additional help for those with lower incomes in a way that aligns the means with the program’s two distinct ends.

It is essential to the effectiveness of this reform that the premium support provided by Medicare be under the control of the beneficiaries. They would be given choices each year for enrolling in competing coverage options, including one administered by the federal government. Their premium-support payments would be calibrated based on a weighted average of the total premiums of the various competing options, including plans offered by private insurers and the traditional, government-administered fee-for-service program. Beneficiaries would have incentives to enroll in cost-effective plans because they would be required to pay added premiums for enrolling in the more expensive options. This design is crucial for bringing into Medicare a strong incentive for cost-cutting and value-seeking.

But this would not be an unprecedented innovation. It would work a lot like today’s Medicare Advantage program, which a third of seniors already choose over the fee-for-service program, but would enable competition among insurance providers and the traditional program to more directly restrain program spending. This kind of premium-support reform might by itself have gone a long way to addressing Medicare’s fiscal challenges if it had been enacted over the past decade. That window is likely behind us, but premium support must still be part of any effective reform of the program.

Reforms to Medicaid must be similarly geared to enabling a more competitive and consumer-driven health sector. The core structure of the program—in which states are reimbursed by the federal Treasury for the money they spend on behalf of beneficiaries—creates incentives for overspending and inefficiency. A more effective and sustainable Medicaid program would be divided into its two distinct beneficiary groups—able-bodied adults and their children on the one hand and the disabled and elderly on the other. The federal government would then make fixed, per-capita payments to the states based on historical spending patterns for the program’s two population groups.

States would be given a lot of room to manage the program within those bounds. Ideally, able-bodied adults and children who are eligible for Medicaid would receive their benefits as a credit for buying health insurance in the private insurance market. And states would be allowed to implement major changes in the structure of the program to address their distinct needs and priorities without requiring cumbersome prior federal approval. In essence, the federal government would act as the provider of a set, defined financial contribution while the states serve as program designers and regulators, and beneficiaries themselves are empowered to make more choices in coverage and care.

The common thread linking these approaches to the largest entitlement programs is a desire to distinguish means from ends so that the misguided designs of our entitlements today are not confused with their appropriate goals. By thinking through the goals while understanding the immense fiscal pressures these programs create, we might see our way to an entitlement system that could be made sustainable in 21st-century America, could particularly help those who need it most while providing a baseline of support for the elderly in general, and could avoid undermining the country’s capacity for growth and prosperity. That combination of goals, rather than a commitment to ignore enormous and obvious oncoming problems, ought to serve as a basis for some bipartisan consensus.

Taking Responsibility

These are, to be sure, only the outlines of reforms to our major entitlement programs. But they draw upon many years of work and scholarship, especially by right-leaning experts, and are available to policymakers in various forms that can be adjusted to meet fiscal, practical, and political necessities.

Attempting any such changes would involve expending political capital. And Republicans should also be willing to trade some such changes for modest tax increases that Democrats might demand in return for their assent—especially if these are tailored to minimize the obstacles they pose to growth. The spending side of the ledger is where the real problems are, but revenue matters too, and no particular tax rate is sacred.

What should be nearly sacred to policymakers is their obligation to avoid avoidable disasters and to reduce the risk of crisis. Such basic responsibility is essential to leadership, and there is no excuse for shirking it year after year. That such recklessness is now thoroughly bipartisan only makes it more dangerous to the country. And the fact that similar irresponsibility abounds at the state and local levels (where many pension plans are one market crash away from catastrophe) makes it all the more so.

The Trump era has distracted many politicians and citizens from these problems, as it has from many other perennial challenges of governing. On the right in particular, many people who seemed genuinely concerned about deficits and debt 10 years ago now pretend these challenges don’t exist. But ignoring them doesn’t make them disappear. In fact, it makes them worse. Viable, politically tolerable solutions are still possible, but they only grow more difficult as the years pass. It’s time to take deficits, debt, and entitlement reform seriously again.

Yuval Levin is the vice president and Hertog fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

James C. Capretta is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.