Published January 17, 2024

I’ve written about an old and very close friend, Joe Mahoney, in this space before. Joe died in an automobile accident on Christmas Eve. He was 80. He left behind a treasured wife of 58 years, eight children, and 24 grandchildren. Most people have many friendships over a lifetime. But real friends, the intimate kind, tend to be few.

This makes sense. The word “friend” comes from the Old English freund, with an Indo-European root that means “to love.” Love is an overused expression in our culture, and overuse cheapens a word’s reality. We can like and admire dozens of other people. But the love of a true friend, like the love of a spouse and family, comes with obligations and strong feelings, including the pain of loss, because it involves giving away part of ourselves.

Most of us have limited room for that kind of generosity. The reason is simple. It involves a high degree of risk. And everything about the nation we’ve created over the past half-century encourages the opposite.

Fidelity is intrusive. It’s a drag on our appetites; a cramp on our ambitions. But it was never that way for Joe. He was an exceptional Catholic man in every sense. A former Marine – he’d argue that there are no “ex-Marines” – he lived the motto of the Corps, Semper Fidelis, in his daily life. In a world of alibis and excuses for infidelity, he was “always faithful” – to his family, his Church, his duties, and his friends.

He was buried with full military honors on January 9, the first day of ordinary time on this year’s Church calendar, at Dallas-Fort Worth National Cemetery. The morning was cold and the wind bitter. From a distance, we watched the casket lowered into the ground. His coffin fit the empty grave perfectly. It left a commensurate hole in the lives of those who loved him.

So much for personal memories. Here’s the point.

Death is an ordinary part of everyone’s “ordinary time.” No one escapes it. And nearly all of us will be forgotten, sooner or later, by everyone but God. The result is predictable.

For the unbeliever, death is an obscenity. It’s an outrage to be evaded as long as possible and eventually somehow wiped away by human ingenuity. That’s a hopeless project, a project literally without hope in something above and beyond time as we know it. But even if such a project could succeed, life in this world would simply mean more of the same, here and now, without end. . .and not for just any child who happened to be conceived.

Immortality would have strings. The planet, so the argument goes, can barely support those of us already here. Fertility is already seen as an ambivalent blessing needing rational control, if not by willing individuals, then by more competent “experts.” This is already implied in our relentless “reproductive choice” propaganda. It drives our international population control policies. In effect, the future is something to be feared unless carefully manufactured and controlled by the more (seemingly) intelligent among us.

Put simply: Nothing proves the foresight of C.S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength more forcefully than the social conditions we see emerging now. Infertility is made a virtue. Big families are vulgar, if not a vice. And empty nurseries are good for business, at least in the short run, because they free women from the burdens of child-rearing, weaken messy and inefficient bonds like marriage and family, and amplify the workforce.

The fewer with human “skin in the game,” the more there is for the flesh and blood lucky few who remain. Or so the assumptions go, and that’s clearly where they lead. The fact that populations age and cultures die in the process is a problem for study at a later date.

Thus our current leadership class is – ironically and blindly – very religious; “religious” in the word’s minimal sense. In our case, the cult’s creedal content is simply another variant of the ideologies that savaged Germany and Russia in the last century. The object of worship is neither working-class revolution nor racial purity, but materialist science and the technologies that flow from it. The result for the human spirit is the same: desecration.

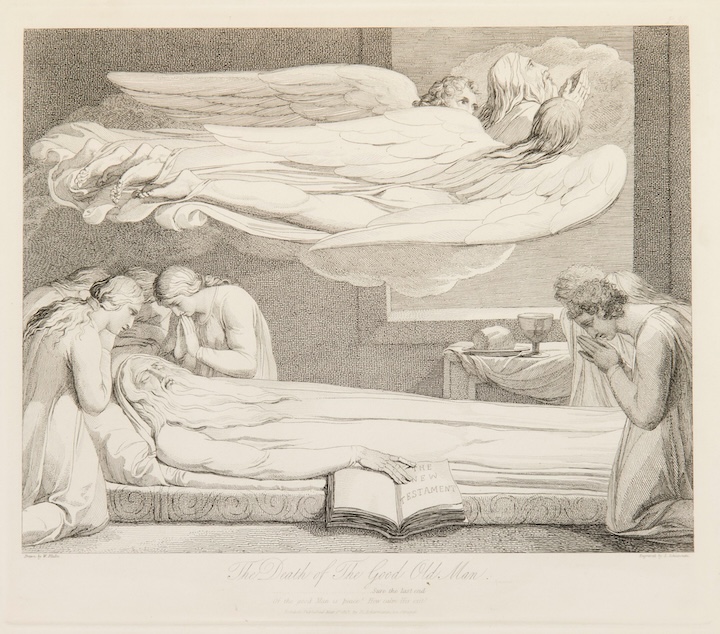

Christians see the world differently. The sadness of loss is the same. The pain of those left behind is just as bitter. And death is surely an end, yes. . .but only the end of a stage. As J.R.R. Tolkien, himself a committed Catholic, wrote in his private letters, the theme of his great novel The Lord of the Rings is not man’s struggle against evil, but rather the gift of death and immortality given to him by a loving God.

In the end, death is not a punishment but a blessing; a “freedom from the circles of the world” and a liberation for something higher and better. Death is a catastrophe, a “sudden turning” in the original Greek sense of katastrophe. But for the believer in Jesus Christ, the turning is a “eucatastrophe,” a deliverance to eternal life and a turning toward joy – forever.

Which brings us back to a cold morning, a bitter wind, and the grave of a best friend.

We headed back from the cemetery, and the tears of Joe’s family flowed freely. But in the end, so did the laughter. A life well lived has purpose and no room for permanent sorrow; so many weirdly funny moments; so much nobility and beauty to remember. God told us to be fruitful and multiply, and to sanctify the world with our lives.

And Joe was a good listener. He leaves a legacy of abundant life in his children and grandchildren, and colleagues and friends, too many to count, that he made better by the witness of his Christian faith. He had skin in the game.

At the end of the day, may the same be said of us.

Francis X. Maier is a Senior Fellow in the Catholic Studies Program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Mr. Maier’s work focuses on the intersection of Christian faith, culture, and public life, with special attention to lay formation and action.