Published January 4, 2019

Imagine American politics as a system of binary stars, one Republican-conservative, the other Democratic-progressive. The stars are separate from each other, yet not independent. They are bound together by mutual gravity—orbiting around a common center of mass—and by their history of reciprocating opposition. Twin masses of flaming, superheated gas act to discipline one another: a system of checks and balances.

One star will be larger and dominant at any given time. But when America works as designed, the two stars are able to exchange roles, one of them shining brighter for now, then yielding to the other. From a distance, their combined light will appear to come from a single source.

Or you could think of the U.S. as a ship plunging along in stiff headwinds. It tacks back and forth, from left to right and back again, and so maintains over the years a middling course. The country goes from Democrats Roosevelt and Truman to Republican Eisenhower, back to Democrats Kennedy-Johnson, then to Republicans Nixon-Ford, to Democrat Carter, to Republicans Reagan-Bush. And so on.

Nature is full of such analogies. The farmer plants a field one year and lets it lie fallow the next. A democracy refreshes itself by alternating its political emphases. In this way, the American people remain approximately sane, and prevent themselves from becoming either totalitarian or bored. (Politics is among other things the pre-eminent form of American entertainment.)

But a binary system will break up if the two stars fly too far apart—if their mutual gravity (or, by analogy, their deeper community as a nation—Lincoln’s “mystic chords”) cannot hold them in tension. Then someone fires on Fort Sumter. That’s the tendency of things now: President Trump’s first two years have unfolded as a drama of cultural secession.

Dialogue fails. Leftist gospels of diversity and gender innovation cannot communicate with red America. An immense incompatibility—of language, sympathy and shared experience—precipitates the defiant nullifications and anarchy of Trumpism.

America once again feels like “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” You remember that the book—sequel to the freckle-faced, sun-shot frolics of the Tom Sawyer version—shows the darker side: alcoholism, child abuse, murder, race hatred, blood feud, fraud, rural moronism. Twain’s 19th-century masterpiece feels fairly contemporary in the 21st. Naturally, school boards keep banning it.

At the end of the story, Huck has a choice between the genteel oppressions of Aunt Sally (big government, in effect, and the suffocations and soul-killing pieties of cultural correctness: “sivilization”) and the bracing anarchy of the Territory. Huck lights out for the Territory. Progressives opt for Aunt Sally—for the schoolmarm’s coercive niceness and the Chinese finger trap of “diversity.”

Trumpism is the 21st century’s Territory, where anything can happen, some of it crooked and sordid, no doubt. This is where scams occur and masculinity is “toxic” and men mansplain and tell lies and fall into unmade beds with dance-hall girls but nonetheless enact a drama that feels, to them, like freedom.

Long ago, in the 1960s, the dissident young lit out for the Territory, telling themselves they were wild and free. By and by, they gained weight, turned gray and commenced to impose their cultural whims upon everyone else. The former Hucks converted U.S. universities, for example, entirely to the regime of Aunt Sally. They now preside over the worst of dogmatic petit-bourgeois correctness: hordes of diversity bureaucrats, invidious quotas, discretionary pronouns, safe spaces and other oppressions. If the Democrats do not purge Aunt Sally from their program—if they don’t manage to lure Huck, who is the real American energy, back from the Territory—then they are going to lose the 2020 election. (But we cannot look that far ahead, of course; Robert Mueller has yet to weigh in.)

Left and right, orbiting each other across talk shows and election campaigns, are imperfect variations on the common theme. The country works best when both sides are aware, at least a little, of their imperfections and acknowledge the larger civics of interdependence. America is a noisy, ever-evolving conversation about what it is and what it ought to be—questions that should remain creatively unsettled.

What worries me now is the progressives’ blindness to their own imperfections. Aunt Sally is always stiflingly right, and Huck, at his best a shrewd and deeply moral deplorable, won’t have her.

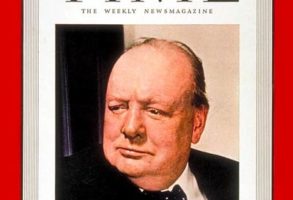

Mr. Morrow, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, is a former essayist for Time.