Published December 8, 2022

Washington Post columnist Ruth Marcus has written a nearly 5000-word critique of originalism titled “Originalism is bunk. Liberal lawyers shouldn’t fall for it.” From its unusual length, its confident pronouncements, and its over-the-top rhetoric (e.g., “insipid,” “rigged, dishonest bunk”), it would seem that Marcus imagines that she has penned a compelling takedown of originalism. But her critique is rife with confusions, straw men, and empty epithets.

At the outset, let me identify a problem that pervades Marcus’s essay. A primary function of any theory of constitutional interpretation is to demarcate the lines between the matters that the Constitution removes from the democratic processes (whether in Congress or in the states) and the matters that it leaves to them. But Marcus seems oblivious to this fundamental matter. She asserts, for example, that originalism “is skewed to a cramped reading of the document [the Constitution], unleavened by modern science and sensibilities.” But if what she means by a “cramped reading” is a reading that, rather than entrenching the rights that she favors, gives broad play to the democratic processes, then “modern science and sensibilities” have lots of room to operate. Marcus instead gives her readers the impression that the Court operates as some sort of monarchical institution that issues decrees that impose policy, one way or the other, on every matter.

Marcus alleges four flaws that originalism suffers from. I’ll address them in turn.

First, Marcus contends that originalism “offers the mere mirage of objectivity and therefore of constraint” and is a “fundamental[ly] futil[e]” enterprise. She quotes with approval the notion that “For most constitutional provisions, there is no ‘original meaning’ to be discovered.”

I have no quarrel with the proposition that there are many constitutional questions to which originalism cannot provide a clear answer. Nor, I think, do other originalists. But that is no reason to dismiss originalism when it can provide a clear answer. And on most of the hot-button questions of the past several decades (e.g., abortion), originalism clearly rejects the favored progressive position.

Originalists recognize the incompleteness of originalism as a judicial methodology, and they differ on important questions such as what level of certainty as to constitutional meaning is needed to decline to enforce a statute. I, for example, have defended a presumption of constitutionality, while many libertarians propose a presumption of unconstitutionality. There are also lots of methodological issues on which originalists hold various views. Marcus could fairly have cited this lack of consensus as a flaw in originalism.

Marcus spends seven paragraphs criticizing “one new weapon [that] has been added to the originalist arsenal,” corpus linguistics. I share Marcus’s skepticism about how much certainty corpus linguistics can provide. But that’s an argument for using corpus linguistics cautiously, not an argument against originalism.

Second, Marcus contends that originalism “is self-refuting: The Constitution itself was deliberately written with grand, magisterial phrases … meant to be interpreted by future generations.” Marcus invokes Chief Justice Marshall’s famous statements in McCulloch v. Maryland that “we must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding” and that the Constitution is “intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.”

Within broad bounds, the Constitution creates a system of representative government in which it is indeed up to successive generations of Americans to decide how we are to govern ourselves. The living-constitutionalist project that Marcus embraces instead contends that the Constitution delegates to “future generations” of judges the authority to invent rights that constrain that exercise in republican government. Insofar as the Constitution has “grand, magisterial phrases” that have no specific meaning, that just takes us back to the question (a few paragraphs above) what the Court should do when originalism cannot provide a clear answer.

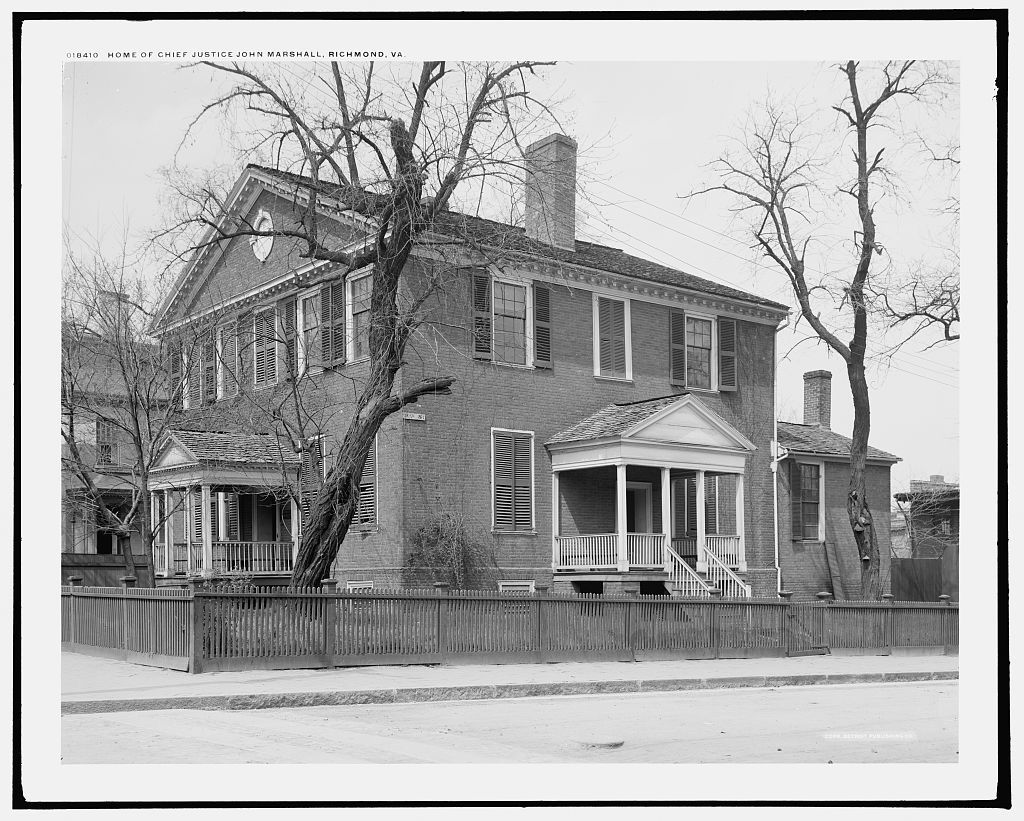

Properly understood, Chief Justice Marshall’s statements in McCulloch cut strongly against Marcus. (More than three decades ago, Justice Scalia condemned the common misuse of Marshall’s statements as one of his “most hated legal canards.”) Chief Justice Marshall was addressing whether Congress had power to establish the Bank of the United States. In the course of determining that Congress did have that power, Marshall states:

A Constitution, to contain an accurate detail of all the subdivisions of which its great powers will admit, and of all the means by which they may be carried into execution, would partake of the prolixity of a legal code, and could scarcely be embraced by the human mind. It would probably never be understood by the public. Its nature, therefore, requires that only its great outlines should be marked, its important objects designated, and the minor ingredients which compose those objects be deduced from the nature of the objects themselves. That this idea was entertained by the framers of the American Constitution is not only to be inferred from the nature of the instrument, but from the language.… It is also in some degree warranted by their having omitted to use any restrictive term which might prevent its receiving a fair and just interpretation. In considering this question, then, we must never forget that it is a Constitution we are expounding.

In the very next paragraph, after noting the “great powers” set forth “among the enumerated powers of Government,” Chief Justice Marshall observes:

[I]t may with great reason be contended that a Government intrusted with such ample powers, on the due execution of which the happiness and prosperity of the Nation so vitally depends, must also be intrusted with ample means for their execution. The power being given, it is the interest of the Nation to facilitate its execution. It can never be their interest, and cannot be presumed to have been their intention, to clog and embarrass its execution by withholding the most appropriate means.… Can we adopt that construction (unless the words imperiously require it) which would impute to the framers of that instrument, when granting these powers for the public good, the intention of impeding their exercise, by withholding a choice of means?

What these passages make clear is that Chief Justice Marshall believed that the powers of the national government that were set forth in the Constitution deserved “a fair and just interpretation” that would “facilitate” their “execution.” That is what he meant when he stated that in “considering this question”—a question of Congress’s power—“we must never forget that it is a constitution we are expounding.” Note also that Chief Justice Marshall’s invocation of what would “be understood by the public” comports with the tenets of originalism.

Chief Justice Marshall’s statement in McCulloch that the Constitution was “intended to endure for ages to come, and consequently to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs” also means something very different from what Marcus implies. In context, it’s clear that Chief Justice Marshall is stating that it is the Constitution’s conferral of broad powers on Congress that enables Congress to adapt those powers to the various crises of human affairs. In other words, this passage provides no support for a vision of the Court as a perpetual constitutional convention, sometimes construing Congress’s powers narrowly, at other times broadly, sometimes inventing new rights, sometimes restricting old ones, all depending on its own view of how constitutional principles should evolve as society changes.

Third, Marcus contends that originalism “is incapable of being strictly enforced without producing repugnant results.”

There is no question that originalism has allowed “repugnant results,” such as our grievous original sin of slavery. But it has not required them. Some of the repugnant results have come from the Court’s failure to apply originalism. Dred Scott is one prominent example. (The dissenters in Dred Scott properly applied originalist principles.) Other repugnant results are the product of a Constitution that leaves lots of important matters to the democratic processes for resolution. The problem, in short, is in us, the American people, not in originalism.

Fourth, Marcus contends that the originalist justices “are originalists of convenience: They apply the method when it suits their purposes and dispense with it when necessary.”

A stated commitment to originalism of course provides no guarantee that a justice will not instead indulge his or her policy preferences. That said, the charge that a justice has deviated from what originalism calls for is in serious tension with Marcus’s claim that most constitutional provisions do not have a discernible original meaning.

Marcus’s evidence that the originalist justices are inconsistent is laughably weak. She asserts that the Court’s rulings last June in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (overturning Roe) and in the New York gun case provide a “dramatic display” of the inconsistency:

In Dobbs, the majority reached back to the 13th century to find that the Constitution contained no protection for the right to abortion — even though, in the gun case decided just the day before, it declared that “historical evidence that long predates [ratification] may not illuminate the scope of the right” at issue.

Similarly, the majority announced in the gun case that “post-ratification adoption or acceptance of laws that are inconsistent with the original meaning of the constitutional text obviously cannot overcome or alter that text.” Then, in Dobbs, it eagerly cited the numerous state laws restricting abortion that were passed shortly after the 14th Amendment was ratified. [Emphasis in original.]

But in Dobbs the Court looked back to the common-law treatment of abortion in order to establish that a right to abortion was not deeply rooted in our nation’s history and tradition. That is a fundamentally different enterprise than determining what the text of the Second Amendment meant when it was adopted. (Plus, Dobbs was correcting Roe’s mistaken account of the common law.)

The proposition that post-ratification laws cannot overcome or alter the text of the Second Amendment is entirely compatible with the single sentence in Dobbs that refers to post-14th Amendment enactments on abortion as evidence that confirms that abortion was not deeply rooted in our nation’s history when the 14th Amendment was adopted. Marcus seems to miss that the Court put much heavier emphasis on the fact that “three-quarters of the States … had enacted statutes making abortion a crime” by 1868, “the year when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified.

Marcus also faults the originalist justices for not showing more interest in originalist arguments about the 14th Amendment at oral argument in the Harvard and UNC racial-preferences cases. But the briefing in the cases focused very heavily on the Court’s precedents, so it’s hardly surprising that the oral arguments did as well. Marcus would be on much stronger ground if she were to discuss the difficulty of implementing originalism in a system suffering from lots of non-originalist precedents.

To her credit, Marcus acknowledges in the closing part of her essay what she calls “the hardest question of all”: What is the alternative to originalism? But she fails to come up with a meaningful answer. Repeating her misconception that originalism somehow prevents the Constitution from applying to and accommodating circumstances that the Framers couldn’t foresee, she writes:

But in the end, judging inevitably involves judgment — one hopes, good-faith judgment based on the individual jurist’s interpretation of the values embedded in the Constitution and the development of those values over time. [Emphasis added.]

That is a very thinly disguised invitation to justices to indulge their policy preferences.

With six appointees of Republican presidents now on the Court, would Marcus really prefer that the originalist justices adopt her approach?

Edward Whelan is a Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center and holds EPPC’s Antonin Scalia Chair in Constitutional Studies. He is the longest-serving President in EPPC’s history, having held that position from March 2004 through January 2021.

Edward Whelan is a Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center and holds EPPC’s Antonin Scalia Chair in Constitutional Studies. He is the longest-serving President in EPPC’s history, having held that position from March 2004 through January 2021.