Published July 28, 2022

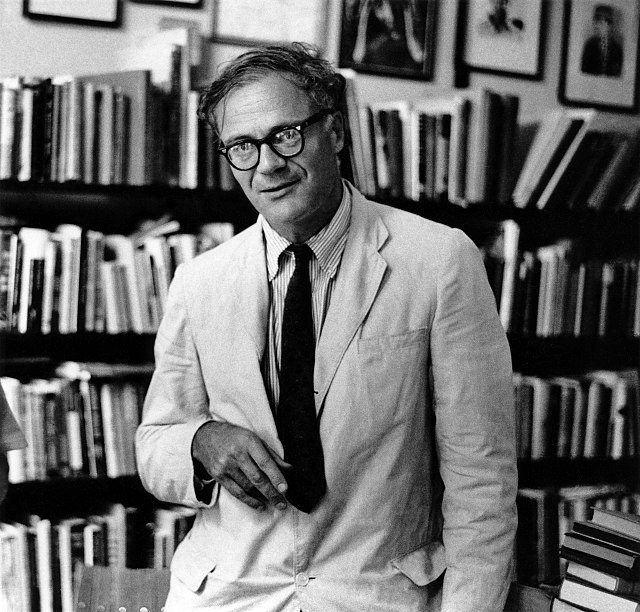

Robert Lowell (1917–1977), still widely considered the supreme American poet of the mid 20th century, was born for greatness and for great suffering — a double whammy quite common among eminent modern writers, and especially poets, for whom madness, drunkenness, and suicide are standard occupational hazards. The newly published Memoirs gathers his prose reminiscences of the family life of his boyhood and youth, the turmoil loosed by his severe manic-depressive illness, and the happiness he enjoyed in fellowship, and sometimes in blood-brother friendship, with his literary peers and superiors, the latter including masters such as Eliot, Pound, and Frost, whom he regarded as his peers. This collection presents new material excavated from typescripts among the Robert Lowell Papers at Harvard’s Houghton Library, and even some therapeutic exercises recovered from a psychiatrist’s files that are held at the University of Texas; there are also memorial essays for dead friends that were previously published in the New York Review of Books and in Lowell’s Collected Prose (1987). The editors, Steven Gould Axelrod and Grzegorz Kosc, justify this double-dipping in the name of textual perfection, having sorted through numerous variants in the foul papers and pieced together the choicest version of each of these essays. In any case one is grateful to have all these writings in a single volume.

Robert Lowell came of distinguished stock, the Lowells of Boston, who in the famous jingle speak only to Cabots, who in turn speak only to God: an all-American aristocracy of talent and a stew of psychic malignancies. Ancestors bearing the Lowell name included a dynamo entrepreneur (Francis Cabot) who had a city named for him; a president of Harvard (Abbott Lawrence); a visionary astronomer (Percival), whose initials are incorporated in the name of the sometime planet Pluto; one famous poet (James Russell), who helped found the Atlantic Monthly and served as ambassador to Spain and the Court of St. James’s; another famous poet (Amy), who won the Pulitzer prize and appeared on the cover of Time. Family records also show a wealth of mental and emotional pathologies down the generations, ranging from “high-strung delicacy” to “alarming excitation” to “nervous prostration” to “complete breakdown of the machine” to recurrent thoughts of “my razors and my throat.”

You salvage what you can from a family shipwreck, and if you are a writer you will likely find all sorts of useful materials for constructing your own seaworthy vessel. Although Robert Lowell did well enough as a poet, and made a meal of familial peculiarity and strife, he might have missed his calling as a comic novelist of manners; witness his quick sketch of his maternal grandmother, Mary Winslow (née Devereux), of Raleigh, N.C.:

Small, witty, untortured, she played bridge twice a week with two different groups and hated two Presidents of the United States: Lincoln, because of the pious tone taken by northerners; and Herbert Hoover, because once, as my grandfather’s superior, he had come to dinner with black fingernails. Nothing bored her more than American history, yet she read whatever French novels the Boston Athenaeum supplied and could name and date the kings of France. She found much to be glum about in my grandfather.

Every sentence detonates quietly and with deadly effect.

Like mother, like daughter: Charlotte Lowell (née Winslow) endured the chagrin of having a husband who lacked the deportment appropriate to his station. “‘I have always believed carving to be the gentlemanly art,’ Mother used to proclaim. Father, faced with this opinion, pored over his book of instructions or read the section on table carving in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.” When things started looking dire at Sunday dinner, he began taking lessons at a carving school — what can’t you learn in Boston? — and brought his shaky erudition to the dissection of roast or bird. “He liked to pretend that the carving master had stated that ‘No two cuts are identical,’ ergo: ‘each offers original problems for the executioner.’ Guests were appeased by Father’s saying, ‘I am just a plebe at this guillotine. Have a hunk of my roast beef hash.’” In this mostly amiable passage one has a taste of the blood that would be spilled when Mother got her own knives out. She nagged her too pliable husband ferociously into resigning his commission as a career naval officer and taking a more lucrative position as an executive of Lever Brothers soap — a job he would hate and ultimately fail at. Maternal dragon fire and paternal paper-doll combustibility form the backdrop for Robert Lowell’s more spectacular blaze of madness, which saw him shatter completely in the firestorm of mania and more or less put himself together again 16 times over some 30 years, and which had him thinking continually of suicide.

“I suffer from periodic wild manic explosions that are followed by long hangovers of formless self-pity.” So Lowell wrote in a prospectus of his hopes for psychotherapy, addressed to his Boston psychiatrist in the late 1950s, and an attempt to explain himself to himself, under the psychoanalytic dispensation. “I think both my depressed and manic periods are merely results of something else that is my real disease.” What really ailed him, he believed, was his compulsive and perverse solitariness, which had its origins in his antipathy toward his parents. He was an isolato, to borrow Herman Melville’s term, who cut himself off, quite willingly and even willfully, from the society of others, which he saw as the province of enviable normal living. Yet even as he envied the contentedly gregarious, he was bent on a discipline and an achievement superior to theirs. “When first married, I had some of the usual dreams: house, children, career, etc.; but mostly I thought of shutting myself to read and write works that would astonish. Society would be a little group of sympathizers and masters.”

Lowell understood his illness at this point as essentially a failing of character, with its matrix in the conflicts of childhood — the Freudian program to a fare-thee-well. Abetting his literary obsessions, he believed confidently at that time, was his Roman Catholic convert’s unfortunate spiritual pugnacity, which pitted his soul against the sinful uncomprehending world, in the Pauline sense of that word, and which led him to spend time in prison as a conscientious objector during the Second World War. Looking at his earlier religious enthusiasm from a new vantage of disenchanted unbelief made him see pathology where there was none.

He would discover later that he and his doctors had the etiology of his disease quite wrong. The irresistible creative impulse, the urge to make something beautiful and to achieve something great, was not a destructive character flaw but a heroic love of excellence, and the key to his extraordinary resilience in the aftermath of his devastating attacks of insanity. And anyhow the crazed lockstep of cyclical ecstasy and despair had little or nothing to do with how badly his parents raised him. Doctors initiated a course of treatment with lithium in 1967 that kept Lowell sane for the next eight years (with the exception of a single brief interlude of relatively mild mania in 1970), breaking the pattern of yearly hospitalization for mania followed by months of sepulchral darkness. The success of the new regimen bowled Lowell over: Incredulous but joyful, he would say, “You mean all that commotion was due to a salt insufficiency in my brain?”

Perhaps the most awful fact about his illness — the one inspiring awe as well as consternation — was that, as the mania was gaining strength and preparing to sweep him away, the poetry arrived in floods. Some of his best work owed itself to the approach of incapacity and horror, while the flagging energy and comparative blandness of his later poetry showed the inauspicious effects of sound mental health.

The vocation and the affliction that were both bred in the bone placed Lowell among the fateful company of “the extremist poets, as we are named in often prefunerary tributes,” the choice spirits cut out for a very hard life and an even harder death — Dylan Thomas, Theodore Roethke, Randall Jarrell, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, John Berryman; one accidental drowning in alcohol, a heart attack at 55 to finish off a manic-depressive lifetime, and four suicides. In the memorial essay “For John Berryman,” Lowell tries out the would-be consolation that most of these ruined colleagues “lived as long as Shakespeare . . . and long outlived the forever Romantics, those who really died young.” Yet this offers scant comfort, he concludes. “I feel the jagged gash with which my contemporaries died, with which we were to die.” That odd final phrase, with a touch of the uncanny, confounds past and future, makes his own awaited death an established and terrible fact, and suggests the governing hand of some inexorable power, an appointed, unavoidable, and unhappy destiny. And yet there is the paradoxical hint of some consolation rather better than Shakespearean length of days: We cursed poets are the chosen ones, our lives and our deaths irrevocably blighted but marked with singular honor, for we will be remembered by others of our kind for as long as men and women make poems from their suffering.

The suffering and the artistic gift were of a piece for Lowell, and he bore the suffering manfully for the sake of the poetic grace he was vouchsafed. The grace was bountiful, rapturous. Of Lowell’s second book, Lord Weary’s Castle, the notoriously hard-to-please Randall Jarrell observed, “One or two of these poems, I think, will be read as long as men remember English.” Some of Lowell’s best poems include “The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket,” “Mr. Edwards and the Spider,” “Skunk Hour,” “For the Union Dead,” “Night Sweat,” and “Waking Early Sunday Morning.” There will always be readers grateful to him for bearing witness to his fruitful agony, and perhaps it was never really up to Lowell himself to say once and for all whether the gift was worth the pain.

Algis Valiunas is a Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a contributing editor to The New Atlantis, a journal about the ethical, political, and social implications of modern science technology.

Elsa Dorfman on Wikimedia via Creative Commons 3.0

Algis Valiunas is a Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a contributing editor to The New Atlantis, a journal about the ethical, political, and social implications of modern science technology.