Published February 2, 2023

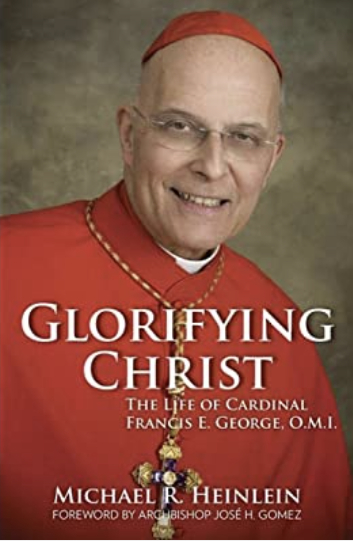

There are a couple of choices for Catholic reading connoisseurs this week. Option A, for those who prefer the high road in Church life, is the new book by Michael Heinlein. Reviewed here by Archbishop Charles Chaput, Heinlein’s Glorifying Christ is a well-researched, beautifully written, and deeply rewarding biography of Chicago’s late Cardinal Francis George. It’s a superior portrait of an exceptional man. More on that in a moment. Option B, for those with a taste for the low road and a leisurely roll in an oil slick of outrage, can be found at Commonweal, here.

One of the least edifying byproducts of the current pontificate is the nastiness of its most passionate boosters; the tendency to see any critic (like a Pell or Müller), any questioning, any serious argument or resistance on matters of substance as “disloyal.” And yet their own pattern of belligerence and refusal to listen creates the obligation to push back.

But enough of the dark side. Let’s focus on something healthier: Option A.

I had one or two friendly conversations with Cardinal George over the years – we had a mutual friend in Msgr. Dick Malone, my wife’s uncle; they’d worked together in Boston before George was ordained a bishop – but I didn’t know him well. His work, on the other hand, I knew very well. It was worth following closely. He was a man of extraordinary intellect and balance, and Heinlein captures both in absorbing detail.

Chicago-born, George contracted polio as a boy. He recovered, but suffered its painful aftereffects for the rest of his life. His experience with the disease barred him from consideration for Chicago’s diocesan clergy, so he turned to religious life instead. He rose to leadership and traveled globally for his order, the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, earned his doctorate in philosophy, and went on to serve as bishop of Yakima, Washington, and archbishop of Portland, Oregon, before his transfer to Chicago. He was the city’s first native-born archbishop.

In action, Francis George was memorable. In Denver, I saw him wing a brilliant 45-minute talk from notes scribbled on a single sheet of hotel notepad. In Chicago, at a Lumen Christi event a year or so before he died, I watched him from the audience as he sat on a panel through a complex, 30-minute presentation on economics. He was already ill with the cancer that would take his life. He looked sound asleep on the stage. The presentation ended. He opened his eyes. He then proceeded to critique and applaud the remarks in precise and articulate detail.

An astonishing mental acuity was routine for George. As many of his brother bishops have since noted, he was “the best and the brightest” of the American episcopate, a man of deep Catholic fidelity and character, honest humility, and one of the few truly great American bishops of the last century. And Heinlein does him justice throughout his excellent biography.

In George’s own words, he saw “promoting and safeguarding the faith” as one of his main duties. He regarded sexual issues, which touch so intimately on human purpose and meaning, as key to a healthy anthropology, but also – therefore – as the root of modern culture’s hostility to the Church. When ideas like freedom and dignity are reduced to sexual license, he wrote, Catholic “moral teaching becomes an object of disdain” and even hatred. He was accused of being a culture warrior, but he adamantly refused the tag. As George stressed, he was about engaging the culture as part of the Gospel’s missionary mandate, and “engagement is not warfare. . .calling it ‘war’ deforms what I’m about.” He also knew that we live in a conflictive time; a time when many people think it’s insulting “as soon as you say, ‘I disagree with you.’ There’s not much I can do about that.” In such a culture, he said

the Gospel’s call to receive freedom as a gift from God and to live its demands faithfully is regarded as oppressive, and the Church which voices those demands publicly is seen as an enemy of personal freedom and a cause of social violence. The public conversation in the United States is often an exercise in manipulation and always inadequate to the realities of both the country and the world, let alone the mysteries of faith. It fundamentally distorts Catholicism and any other institution regarded as “foreign” to the secular individualist ethos. Our freedom to preach the Gospel is diminished.

George worked hard to be what he called “simply Catholic;” a man of the ecclesial center. He was a vigorous proponent of Church teaching on the right to life, the dignity of the unborn, and the nature of marriage and family, but an equally strong advocate for the needs of the poor and the Christian duty to respect all persons, including those with same-sex attraction. As Heinlein recalls, George “often suggested that things would get worse [for the Church] before they got better” – not as an ironclad prophecy, but as a way to force people to think soberly about the health of their own faith and the future of their society. At his core, George was a man of hope and absolute confidence in Jesus Christ.

We live at a moment when we urgently need the witness of good Christian men and women. In the life of the Church, we need leaders of courage and Catholic fidelity; men who will accompany the poor and the broken. . .and also lead them authentically to God. Francis George was exactly such a man. Thus it’s both odd and disappointing that the Chicago Archdiocese has avoided celebrating his legacy since his 2015 death. And as a close reading of the text implies, and others have suggested, that resistance has also included Heinlein in his work. No matter. Michael Heinlein has written a great biography of an exceptional Christian leader. We need a lot more of the same.

Francis X. Maier is a senior fellow in Catholic studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Francis X. Maier is a Senior Fellow in the Catholic Studies Program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Mr. Maier’s work focuses on the intersection of Christian faith, culture, and public life, with special attention to lay formation and action.