Published February 2022

When I used to teach English and what was then called “General Studies” to budding scientists, one of the essay questions I most often set for them ran more or less as follows: “Should a country’s science policy be determined by its politicians or by its scientists?” I liked it because it was the only one of the hundreds of essays I must have set over the years which had what I thought to be an indisputably right and wrong answer, though the right one was not usually the one my pupils argued for. Those young scientists would naturally tend to answer in favor, as they saw it, of their chosen profession, but the less narrowly focused among them could occasionally see all by themselves — or be brought to see — that those who exercised the public trust (namely, politicians) would betray that trust if they turned such a responsibility over to someone else, anyone else, who had not been chosen at the ballot box. Moreover, scientists are necessarily equipped to focus only on scientific problems and have no particular expertise in assessing the political, social and economic aspects of those problems, which can be and often are of more moment to a country than the merely scientific ones.

I suspect that neither Anthony Fauci of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases nor Francis Collins, recently resigned director of the National Institutes of Health, would have been among the cleverer or more far-seeing of those pupils if they had been in my class. Dr Fauci, who had the arrogance to put himself above criticism by identifying himself with “Science” (“It’s easy to criticize. But they are really criticizing science. Because I represent science and that’s dangerous.”) could only have reached such a pitch of absurdity after first coming to think of himself as the czar of the pandemic, answerable to no one but himself and certainly not to the American people, as his ostensible political masters are. He apparently sees it as his entitlement to determine not only the country’s science policy but, by insisting that the government make that policy take priority over everything else, its economic, legal, defense and educational policy as well. Likewise, we now know that Dr Collins took it upon himself to decide American foreign policy by unilaterally suppressing suspicions of the virus’s leak from a Chinese lab on the grounds of preserving “international harmony.”

Such men cannot have learned that kind of arrogance in medical school — though medical students of today may be learning it, along with a lot of other grievously mistaken political precepts once thought to have had nothing to do with the study of medicine, thanks in part to their example. No, they learned it where every other self-entitled jack-in-office learns it today, from the media. Their folie de grandeur is only a viral variant of the media’s, and of the media’s now apparently ineradicable assumption of their own political and moral authority. As in the case of the media, too, that putative authority is constantly encroaching on political authority, which is too often conceded to its claimants by politicians terrified of the potential scandal of a refusal.

Just look at how even so mild a dissent from “expert” opinion as Donald Trump’s self-described attempt to prevent panic by “playing down” the seriousness of the virus in the pandemic’s early days — he said that it might go away in warmer weather, like the seasonal ‘flu — was enough for Joe Biden during the election campaign, to blame him for every one of the 200,000 deaths then attributed to the virus. I don’t remember the media calling foul about such an outrageous accusation. Nor have they raised a similar one against Mr Biden, now that he has presided over an even greater number of deaths. As the previous three-and-a-half years of the Trump administration showed so clearly, moral denunciation of Republicans and moral preening by themselves is now the only language spoken by establishment media and establishment Democrats alike.

For that, as for the usurpation of political authority by “experts” — not, that is, by “science” but by politically motivated scientists — we therefore have to thank the media’s scandal culture. How nice it would be to think, now that we are approaching in June the golden jubilee of the storied Watergate break-in and subsequent purging of a president, that the public had finally had enough of the media’s childish conceit of themselves, born of that scandal, as virtuous heroes of the eternal struggle of the good against the Evil One — who, half a century ago, appears to have broken free of moribund theology and begun to walk among us in the guise of Republican presidents. The precipitous decline in trust of the media since those heady days would seem to suggest as much, and yet the scandal of Republican government continues to be their bread and butter — presumably for all time, and not without effect in the political life of the country.

For a short time in late 2016 and early 2017, after Mr Trump’s election in spite of the evils continually alleged against him during the campaign, it seemed as if we might dare to look forward to an ultimate release from the rhetorical prison of scandal politics. By that time, scandal culture had long since been reduced to self-parody as Keith Olbermann purported to identify on a nightly basis “The Worst Person in the World.” And then, with the election of Mr Trump it briefly appeared that scandal itself had lost its potency as a political weapon. He had seemed a joke candidate to the media partly because he was assumed to be uniquely vulnerable to the scandal-monger’s poison pen. But when the media pushed all the old familiar buttons, nothing much happened.

The people who hated Mr Trump still hated him, but those who liked him still liked him, and perhaps liked him all the more for the disingenuous attacks on him in the media. He himself, you will remember, joked about this when he said that “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters.” I believe that a big part of the reason for the Trump Derangement Syndrome that still afflicts the media and most of the Democratic party is the terror that this apparent superman initially inspired in them when their hitherto most effective political weapons bounced off him. Indeed, insofar as the sword of scandal was employed by the self-righteous elites whom the Trump campaign had been built around attacking, the media’s attacks on him only seemed to make him stronger.

His sixteen Republican rivals for the nomination must have felt the cold hand of failure grip their hearts when they heard the cheers of the first debate audience which greeted his denunciation of “political correctness.” That in itself should have been scandalous, in the view of the politically correct, but it quite clearly wasn’t. No more were the candidate’s sexual peccadillos or his disrespectful and, by the lights of the p.c. crowd, sexist remarks directed at women. Could it be, some of us were then beginning to wonder, that the public were simply fed up with the seemingly endless succession of scandals by which the media had for so long sought to persuade voters that the politically disfavored were bad men (or, occasionally, women) and unworthy of holding public office — like their great mythic prototype, Richard Nixon, vanquished victim of the ur-scandal of Watergate?

Indeed, it is still not clear that scandal has quite regained all its old effectiveness, as the faltering attempts by the media and their Democratic acolytes to turn January 6th into another September 11th may be thought to illustrate. But when the Attorney General of the United States announced in January that America’s Most Wanted were now the January 6th rioters of the previous year — since, in his own words, “there is no higher priority” for the U.S. Department of Justice than tracking down and prosecuting those who were “criminally responsible for the assault on our democracy” — you’d have to be a pretty extreme partisan yourself not to raise an eyebrow at such a blatant and unashamed example of the politicization of American law enforcement. At least during the “Russian collusion” fiasco of 2017-2019 the FBI and Justice Department holdovers from the Obama administration had attempted, not very effectually, to keep their political motives hidden. That they are now so far out in the open suggests that the progressive elite are confident of their own success in persuading people that Trump supporters are scandalous ipso facto: the Worst People in the World, as Keith Olbermann would put it.

They may or may not be right about this success. At least we can hope that those who are not fanatical partisans themselves will eventually see through the spin of those who are. But if, after the initial shock of the Trump election, the media have regained all (and then some) of their old confidence in the politics of scandal — and, with it, their assumed posture as respected moral arbiters for the nation — it must be because of their earlier success, during the pandemic, in identifying their own elite status with that of scientific expertise. “We believe that” (among other things) “science is real,” as some of my neighbors have lately taken to notifying the world by printed signs on their lawn.

They speak for the media as Doctors Fauci and Collins do for science. Insofar as this gnomic apothegm means anything at all, it must be that they pledge their faith in the good doctor and, with him, in the media who confirm him in his self-conceit that he represents “science.” It is a sort of unified field theory of the meritocracy — namely, that the scientific elite are as one with the media elite, who stand as guarantors of each other’s inerrancy in pronouncing on what they see as the salient moral and political issues of the day. Such true believers in “the Science” and its representative on earth cannot constitute anything like a majority of the American people. Indeed, since they see themselves as belonging to a privileged class by virtue of morality and intellect, disdain for the majority must go with the territory.

But the remaining faith of the majority in science cannot but be undermined by the evidence, every day clearer for all who are not parti pris to see, of science’s corruption by politics. In this it is no different from every other discipline of the mind and spirit which has been so corrupted to a greater or lesser extent by the intrusion of quasi-Marxist political thought into its understanding of itself and the world. Like Attorney General Garland, the professors of these disciplines now make no secret of the fact. Like him too, perhaps, they see “the new knowledge” (as Robert Browning once so memorably put it) not as corruption but as a needful correction of now-outdated modes of thought.

Yet “science” somehow retains much of its old prestige, or so I conclude from the willing submission of democratically elected governments across the world to the demands of a scientific establishment that the media tell them is tantamount to “science” itself. This is particularly apparent with respect to the twin problems of climate change and the Covid-19 pandemic. Even the apparently bullet-proof Donald Trump, after his initial misstep, dared not deviate except in minor matters from what his approved scientific advisers were telling him about the pandemic. Of course he was crucified anyway for the minor matters (remember hydroxychloroquine?), as he was for everything, real or imagined, that the media could find to allege against him. But then he caught the virus himself and, after being hospitalized for three days, shockingly announced: “Don’t be afraid of Covid. Don’t let it dominate your life.”

As it happened, this exhortation was made, whether the President knew it or not, the day after the Great Barrington Declaration had said essentially the same thing: that the fears of the scientific advisers to governments around the world had led, or were likely to lead, to worse consequences for public health than those of the disease itself. Here were eminent scientists — Sunetra Gupta of Oxford University, Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford and Martin Kulldorff of Harvard and then hundreds more who signed their Declaration — who dared to suggest that their scientific colleagues were making a huge mistake and, therefore, that “science” was not the same thing as the consensus of government- and media-approved experts.

Naturally, this could not be tolerated by the latter. Dr Collins, as we now know, corresponded with Dr Fauci with a view to suppressing the rival narrative of what they professed to regard as a “fringe” group of scientists. “There needs to be a quick and devastating published takedown of its premises,” wrote Dr Collins to Dr Fauci in an e-mail about the Declaration. “I don’t see anything like that online yet – is it underway?” In the end, such a “takedown” was hardly necessary, as the media were equally concerned about this deviation from the official narrative and denied the Great Barrington scientists — whose efforts were signed onto hundreds of thousands of ordinary people — the oxygen of publicity.

Such politico-scientific skullduggery is reminiscent of the hack in 2009 of e-mail correspondence at the Climatic Research Unit of the University of East Anglia in Britain (see “It’s only common sense,” in The New Criterion of January 2010). There, scientists were revealed — or appeared to have been revealed — as having fretted among themselves about the failure of then-recent data to conform to their climate models and then, instead of changing the models, to have suppressed or minimized the data. If today you read the Wikipedia entry under “Climatic Research Unit email controversy” you will be reassured that the only villains in the affair were the hackers of the East Anglian e-mail servers and the “climate change denialists” who subsequently tried to use the information thus obtained to discredit the blameless climate scientists — and, with them, the politically salient climate science which still informs the media’s understanding of climate change to the exclusion of every other consideration.

As a non-scientist myself, I have no way of knowing if this view of the matter is correct or not, but I do know that these scientists, like the good doctors Fauci and Collins, knew that their careers and research funding, not to mention their influence with governments across the world, were at stake for them in their vehement denials of wrong-doing. Can it be unduly cynical to harbor a doubt or two about their truth? Here, then, is another answer to the question of why scientists should never be allowed to wrest policy-making from the hands of politicians: because the assumption of political authority prevents them from admitting to error, as non-political scientists have always had to do before they could make any progress in science. Lacking a democratic mandate, the political scientists’ authority depends absolutely on their media-conferred reputation for infallibility — which is why the media continue to protect, through all his deceits and tergiversations, Dr Fauci’s self-identification with “science.”

The rest of us would do well to remain skeptical. Scientists turned politicians automatically become politicians first, scientists after. In yielding to the temptations of power, they must pay the price for it that the media demand: the price of participation in the media’s Manichaean division of the world between the forces of good and evil. That division is necessary both as an affirmation of the media’s chosen ones as leaders of the forces of good and as a corollary of the scandal culture which has become the chosen instrument of one party, at least, for gaining and keeping political power. Even when “the science” speaks with one voice — perhaps especially when it speaks with one voice (again, like the media) — it may be right but it can no longer be trusted to be right.

James Bowman is a Resident Scholar at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

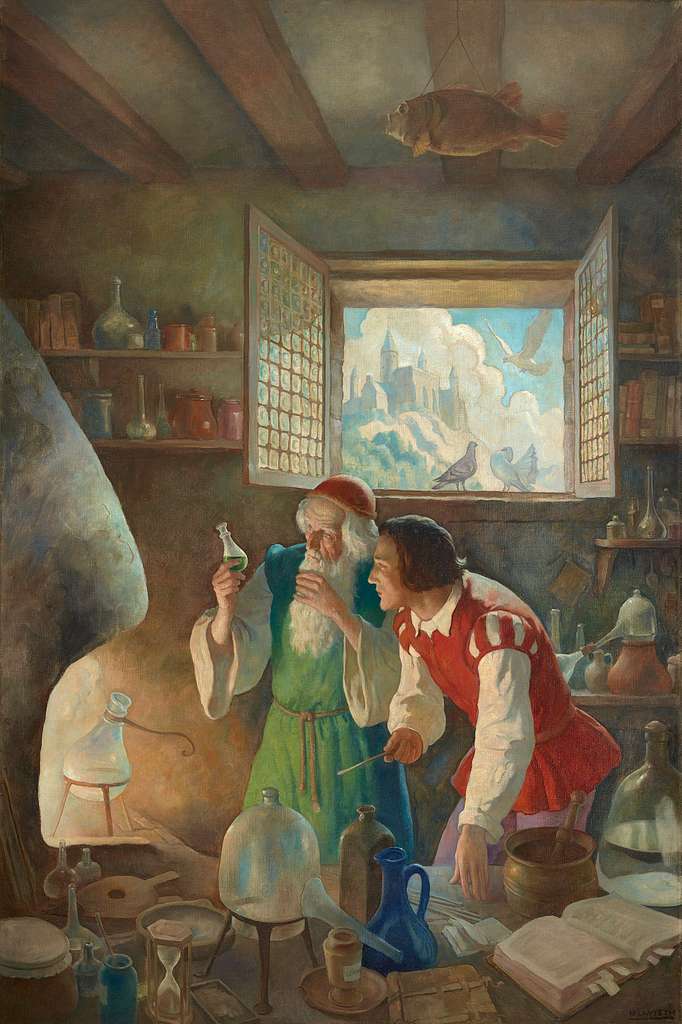

File:The Alchemist N.C. Wyeth 1937.jpeg – Wikimedia Commons

Mr. Bowman is well known for his writing on honor, including his book, Honor: A History and “Whatever Happened to Honor,” originally delivered as one of the prestigious Bradley Lectures at the American Enterprise Institute in 2002, and republished (under the title “The Lost Sense of Honor”) in The Public Interest.