Published April 6, 2019

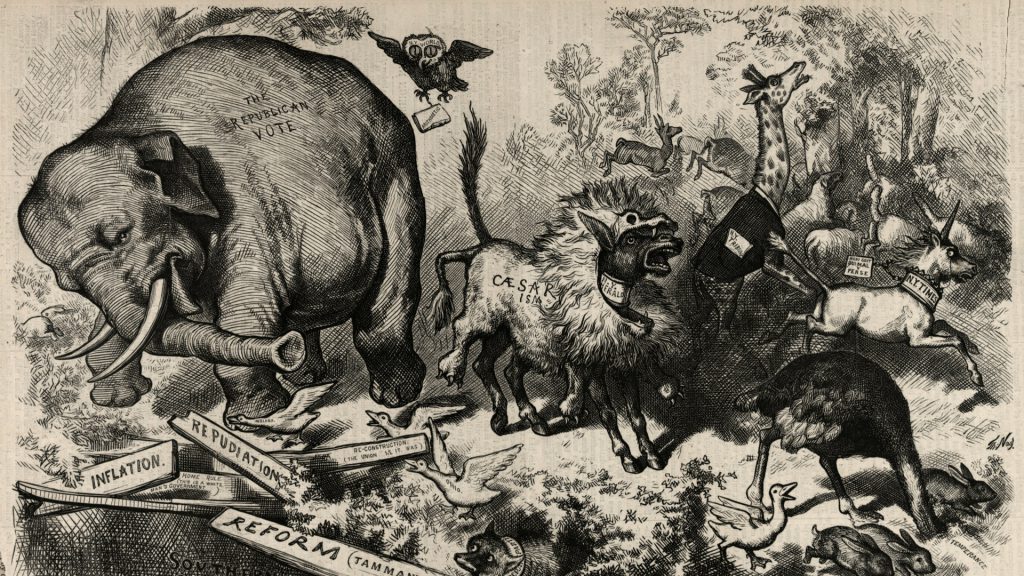

This is an age of cartoons—a time of intense exaggerations and exaggerated personalities. The president is a master cartoonist, with a gift for caricature and ridicule: “Crooked Hillary,” “Lyin’ Ted,” “Little Rocket Man,” and so on. His instincts are hyperbolic. Not long ago he lampooned the House Intelligence Committee chairman as “Little Pencil-Neck Adam Schiff.” His most interesting cartoon is himself, a work entirely of his own contriving, with a touch of the Tasmanian Devil.

The political landscape is alive with cartoons. With a former Nevada state legislator’s accusation that Joe Biden kissed her inappropriately on the back of her head five years ago, the former vice president was confirmed in his reputation as the Pepé Le Pew of American politics—or, if you like, the friendliest man on the planet.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez reminds me of Olive Oyl, Popeye’s girlfriend, whom Wikipedia describes as “foolish, full of energy, enthusiasm, and the joy of living.” When Robert Mueller was investigating, I had a stray vision of him as Elmer Fudd: “Be vewy, vewy quiet. I’m hunting wabbits!” Once you start seeing public figures as cartoons, the spectacle becomes more frolicsome and vivid and entertaining.

In a history of cartooning, you may learn that the 18th-century artist William Hogarth, a great allegorical caricaturist, had a favorite pug dog named Trump. Out of sheer affection, Hogarth painted the dog into some of his scenes. It’s fun to think that in a former life Donald Trump was Hogarth’s pug.

Understanding politicians as cartoons is a way to appreciate the surreal quality of 2019. No doubt the cartooning will become increasingly intense as the 2020 campaign unfolds. Candidates will be cartooned and will strive to cartoon themselves in order to attract attention and distinguish themselves. The logic of primaries, pushing opinions toward extremes, will call forth prodigies of cartooning: character assassinations directed at opponents, with concomitant orgies of preening and gestures of ideological extravagance. Already we see the Democrats’ utopian cartoon of a Green New Deal, accompanied by their revived enthusiasm for socialism—a passion that proves among other things that the 21st century learned nothing from the 20th.

Exaggeration is as American as cherry pie. Teddy Roosevelt was a cartoon. Cartooning has been the essence of the expansive American genius—in politics and patriotism, in humor and advertising. Today social media—the hectic democracy of smartphones, instantaneously responsive to any spurt of adrenaline—exaggerates the American tendency toward exaggeration. Cable television is organized as a smorgasbord of niche hyperbole. Diversity and identity politics produce yet another multiplier effect. Ideology is the most fantastic cartoonist of all.

Sometimes, cartooning is scurrilous and dangerously divisive. Prejudice expresses itself through the cartooning of the other—anti-Semitic and anti-black images, and recently caricatures of the prophet Muhammad. People may struggle all their lives to cease being cartoons in other people’s heads.

The old Road Runner cartoons might be studied to understand the metaphysics—the theodicy, you might say—involved in cartoons. The triumph of innocence is the outcome of the story in the cartoon world, though not necessarily in the real one.

First lesson: There are no lasting consequences. Wile E. Coyote falls 1,000 feet into a canyon, landing in a distant, muted “Poof!” Or he is crushed by a 3-ton boulder. Then the screen goes dark for a second and the coyote returns, good as new, to begin a new round. In the cartoon world, such miracles occur routinely, persuading children that the world is violent yet essentially harmless—a very American misconception.

A second principle: Each cartoon creature always acts in character. The coyote cannot be other than the coyote; he cannot deviate from his role. The basic situation is bleakly existential: A scrawny obsessive in the desert is bent on killing and eating the even scrawnier Road Runner. It is a plot from Samuel Becket or, better still, Cormac McCarthy. Yet the American genius of the animator Chuck Jones (who learned his art from Mark Twain) made it hilarious. The Road Runner is always himself, the trickster-Houdini of blithe evasion: “Beep beep.” Acme supplies the equipment and the earthquake pills. These are the principles of tragedy hijacked into farce for the amusement of kids: Aristotle’s hamartia played for laughs.

Donald Trump has a quality of the trickster-Houdini about him, one that has maddened his enemies. They did not conceive that he could, for example, survive his attack on John McCain as a loser, not a hero. Yet Mr. Trump sailed on, multiplying his affronts. Democrats on the earnest, Cromwellian left should consider that the American spirit may indulge a sneaking admiration for the brash and outrageous and fraudulent and irrepressible. You see the quality in Daffy Duck, in Bugs Bunny.

The 2020 campaign is going to be long and exhausting and epic—historically consequential, but humorless on the whole and filled with the usual dreary chicanery. It will help now and then to appreciate the show as a cartoon.

Mr. Morrow is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.