Published April 21, 2021

George Weigel’s weekly column The Catholic Difference

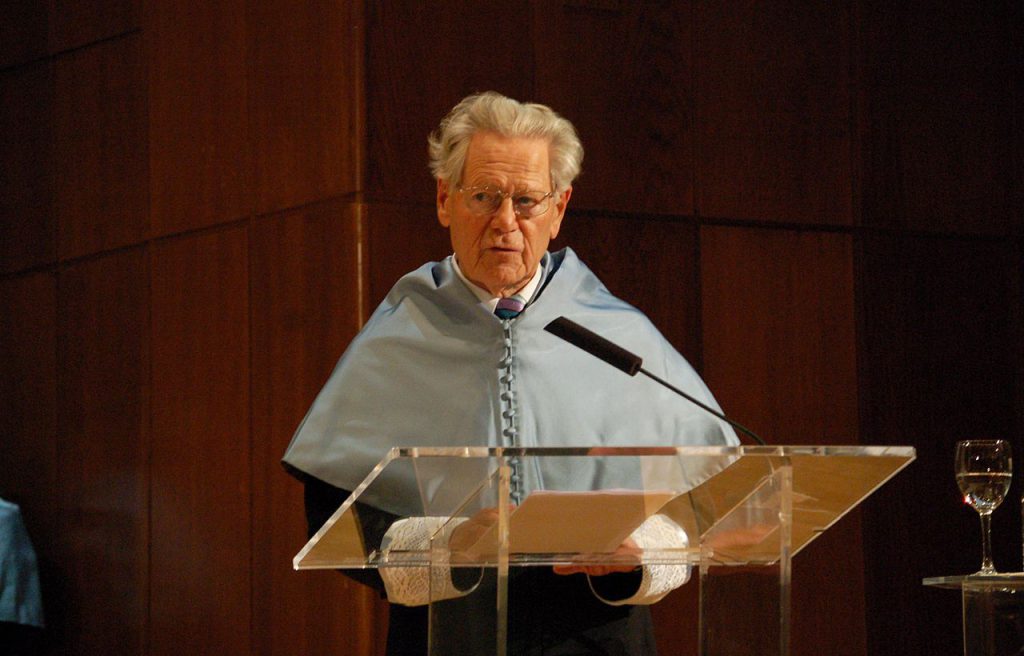

During his 1977 rookie year with the Baltimore Orioles, future Hall of Famer Eddie Murray got a piece of advice from veteran Lee May: If you’ve got talent, May told the 21-year-old slugger, fame can’t help you, but the odds are it’ll ruin you. Murray followed May’s sage counsel and avoided the limelight. Father Hans Küng, the mediagenic Swiss Catholic writer who died at age 93 on April 6, didn’t. Therein lies a sad tale.

Hans Küng certainly had talent. His doctoral dissertation on Karl Barth, arguably the greatest of 20th-century Protestant theologians, became a pioneering book in ecumenical theology. His small tract, The Council: Reform and Reunion, helped frame the discussion at Vatican II’s critical first session. Küng could also recognize and promote talent; he personally engineered Joseph Ratzinger’s appointment to a professorial chair in the prestigious theology department at the University of Tübingen.

Yet, mythologies notwithstanding, Hans Küng had virtually no impact on the great documents of the Second Vatican Council. During the council years, he spent more of his time in Rome with the world press and with the “Off Broadway” council of public lectures and debates than doing the harder work of developing Vatican II’s texts. Ratzinger, by contrast, made critically important contributions to several conciliar documents. So did Belgian theologian Gérard Philips, who got (at best) .0001 percent of the media attention Küng received, but who was so influential in developing what the Council actually taught that another important Vatican II theologian, French Dominican Yves Congar, joked that “Vatican II” should be renamed “Louvain I,” after Philips’s university.

During and after the Vatican II years, Hans Küng invented and then exploited a new personality type: the dissident Catholic theologian as international media star. Handsome, articulate, and a reliable spokesman for the progressive cause of the moment, Küng was one of the first Catholic intellectuals to figure out that the world press couldn’t resist the man-bites-dog storyline in which a Catholic thinker challenges Church doctrine—and does so in ways that confirm progressive cultural biases. Thus the man who once wrote a truly bold book (Justification: The Doctrine of Karl Barth and a Catholic Reflection) became more of a media personality than a serious Catholic theologian. And with the 1971 book Infallible?: An Inquiry, Küng declared himself in sharp dissent from a defined dogma of the apostolic faith.

Thus whatever his influence among the Davos elites—and one must hope that this man who never left the priesthood had some spiritual impact within that ultramundane world—it’s arguable that Hans Küng’s most serious contribution to theology after his book on Barth was an accident of the academic sabbatical system. For as he was about to go on leave from the university one year, Küng asked Joseph Ratzinger to take over one of his Tübingen courses—and Ratzinger’s lectures in that course became the international bestseller, Introduction to Christianity.

Hans Küng was admirably clear about his position: He did not believe to be true, nor would he teach as the truth, what the Catholic Church definitively taught to be true. Thus it should have come as no surprise to anyone when, on December 15, 1979, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith agreed with Father Küng, declared that he “could not be considered a Catholic theologian,” and withdrew his mandate to teach as a “Professor of Catholic Theology.” The German episcopate agreed with CDF’s decision, which reflected the bottom-line Catholic conviction that, thanks to the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, the Church abides in a truth it can articulate authoritatively, even as its understanding of that truth develops. (Things have, obviously, changed among the German bishops.)

The last decades of Hans Küng’s life were marked by bitter attacks on Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI—although the latter, always the Christian gentleman, invited his old Tübingen colleague to share an afternoon with him at Castel Gandolfo, shortly after his election. At certain points, as I noted in a 2010 open letter to Father Küng, those anti-papal polemics descended into the toxic waste dump of calumny, not least because of Küng’s inability to liberate himself from liberal shibboleths on everything from abortion to AIDS to Catholic-Islamic relations to stem cell research—a sorry record for an intelligent man.

Lee May’s warning to Eddie Murray was spot-on: Fame is dangerous. Which is why, to paraphrase F. R. Leavis on the literary Sitwells, Hans Küng belongs more to the history of publicity than the history of theology. Requiescat in pace.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington, D.C.’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.