Published February 12, 2024

The Utah state legislature is about to consider a bill that would transform public higher education, beginning at the University of Utah, and quite possibly spreading from there across the country. The bill, S.B. 226, would restore the kind of Great Books curriculum centered on Western civilization, American history, and civics that was central to American higher education until the past few decades.

Should S.B. 226 become law, Utah will surely be regarded as a national model. And as we’ll see, Utah is more than up to the challenge. (I co-authored the model General Education Act that inspired S.B. 226 along with Jenna Robinson of the Martin Center for Academic Renewal and David Randall of the National Association of Scholars.)

The new bill, S.B. 226, is called the “School of General Education Act” because it establishes an independent school of general education charged with designing and teaching a set of courses that all students must take in order to graduate. Instead of the usual smorgasbord of hundreds of hyper-specialized courses that students choose from in order to fulfill their general-education requirements, UU students will take classes that cover the basics of Western and American history — and that introduce them to non-Western cultures as well. Students won’t have more required courses than students at other schools. But courses that satisfy requirements will be fewer in number and taken in common.

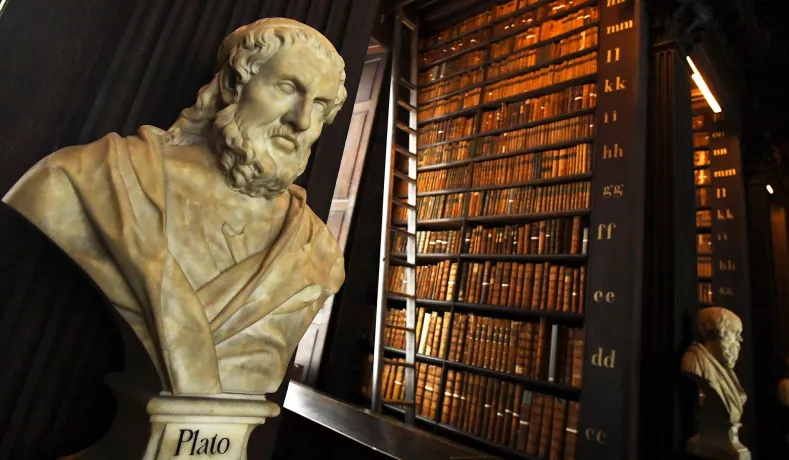

All students will read Homer, ancient Greek philosophy, Greek tragedy, and substantial selections from the Old and New Testaments. Students will encounter the Renaissance, the Reformation, parliamentary democracy in Britain, the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise and fall of the Soviet state and Nazi Germany, not to mention similarly broad survey courses on American history, civics, literature, and much else besides. The likes of Plato, Augustine, Luther, Shakespeare, Montaigne, Austen, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Frederick Douglass will be on the menu. This is classic general education of the kind once made famous by schools like Columbia University (which has never abandoned the approach), the University of Chicago, and Harvard.

S.B. 226 goes further by setting up an independent school of general education, run by a dean who can hire substantial numbers of new faculty members capable in, and committed to, traditional general education. The bill also empowers UU’s board of trustees to reduce current programs and faculty by a number equivalent to the new hires in the school of general education.

No one political party or ideology has a monopoly on classic general education. No doubt plenty of traditional liberals as well as conservatives will be hired to teach the core curriculum. And while some current faculty will be let go, plenty of adherents of today’s postmodern orthodoxies will surely remain. In other words, no professorial point of view will be excluded from the university. Thus, a happy by-product of the return to traditional general education will likely be greater overall intellectual diversity at UU.

Students, for example, might take the new, required American history survey, focused on more traditional topics, in freshman year, followed if they choose by an elective race/ethnicity/sexuality-focused upper-level U.S. history course in their junior year. In other words, over four years, students will experience a mixture of the new, required classic general-education courses and the older postmodern-style courses already on offer. Students will be able to compare and decide which approach, or combination of approaches, they prefer. The marketplace of ideas will return.

The Utah legislature just passed a comprehensive ban on DEI training programs and required faculty DEI statements at public universities. Well done, Utah. Sadly, however, prohibiting administrative adoption of DEI does not, by itself, address the core failings of the modern university. Part of the unsolved problem is that professors have abandoned the traditional concept of academic freedom according to which they should avoid imposing an ideological orthodoxy on students. Professors once thought they owed students an honest accounting of competing positions so that students could develop a worldview for themselves. For too many professors, that ethic of intellectual tolerance is no longer operative.

Another often-overlooked part of the problem is hyper-specialization. Instead of giving students the sort of knowledge that all informed American citizens need, professors teach their narrow (and often thoroughly ideological) specialized research. Between the ideological slant and the hyper-specialized subject matter, students never get the big picture.

Classic general education addresses these problems with broad survey courses conveying fundamental knowledge. Traditional general education also sets up conversations or debates between great thinkers across time — say, Adam Smith versus Karl Marx, or an ancient, like Aristotle, versus a modern, like John Locke, or a founding conservative like Edmund Burke, versus a founding liberal, like Tom Paine. Classic general education doesn’t “deconstruct” or dismiss these great thinkers as outdated. It takes them seriously as at least potentially having something to teach us today, even if sometimes by their failings. When all students share some familiarity with these thinkers, because a subset of all courses are taken in common, they spontaneously put the great books into debate outside of class. This is what has been lost, and it yields not only knowledge and intellectual excitement, but civility and tolerance.

But does a legislature have the power to mandate this sort of required curriculum without violating academic freedom? You bet it does. In fact, general-education requirements are mandated by elected or appointed political officials all the time. We just don’t notice it. Typically, general-education requirements at public universities must be approved by boards of trustees (sometimes called “regents” or “governors”). Public-university trustees are either appointed by political officials, like governors and state legislators, or directly elected by voters. In other words, trustees represent the public, and the decision as to what sort of knowledge to require at university is ultimately a public responsibility.

Trustees must select or approve general-education requirements because the kind of knowledge that a university chooses to mandate reflects a set of values. Those values are a matter of public choice, not professorial expertise. Academic freedom guarantees that a professor’s individually designed course should be largely under his own control. But academic freedom does nothing to guarantee that such a course be declared a graduation requirement. That is a matter for the public to decide, through its representatives (trustees and legislators).

The real problem with higher education is that trustees and legislators have ceded their control over the general-education curriculum to a faculty driven by political motives. Typically, trustees simply rubber-stamp whatever general-education curriculum the faculty proposes. And increasingly, the faculty chooses general-education courses based on its political leanings, not on academic expertise. That is why so many schools now adopt general-education requirements that inculcate DEI, critical theory, sustainability, global citizenship, and any number of other ideological positions, rather than components of knowledge designated as necessary based on specialized academic expertise. (Only the latter is the basis of academic freedom.)

If legislators and trustees abandon their responsibility to steer the broad educational mission and strategy of public universities — an inevitably values-laden task — then the faculty will insert its own political values in their place, something in no way justified by academic freedom. The choice between a DEI-based general-education requirement and a Western civilization general-education requirement is a choice of values, not academic expertise. And here is where trustees and legislatures have not only a right, but an obligation, to step in.

But is general education really a matter for state legislatures and not just trustees? It absolutely is. It’s true that legislators often leave the issue of general-education requirements to trustees (who in turn simply rubber-stamp faculty decisions). Nonetheless, at numerous points in our history, legislatures have intervened to establish general-education requirements. Last year, when Florida governor Ron DeSantis supported legislation imposing general-education requirements on Florida, I defended that bill by recounting Thomas Jefferson’s legislative moves to revamp the departmental structure and curriculum of the College of William and Mary, and to establish the instructional objectives of the University of Virginia, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

In the 1920s, 23 states (nearly half of the then-48 states), either required public universities to offer courses in the U.S. Constitution or established such courses as graduation requirements. This movement was successful in large part because it had the support of university presidents across the country. The American Political Science Association — the most important national organization of political-science professors — actually published a model bill designed to render such laws more uniform by converting Constitution courses into full-blown graduation requirements, rather than simply legislatively mandated elective offerings. One of the main powers behind this state legislative movement was the American Bar Association. The movement almost certainly also enjoyed the private endorsement of the then-Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, former president William Howard Taft.

There was little public opposition to this movement, and such opposition as there was never raised professorial academic freedom as an issue. Some argued that curriculum mandates were ineffective and ill-advised, but this was framed as a matter of practicality, not principle. In fact, the objection to legislative control of curriculum was largely focused on Constitution courses at the K–12 level, not college. Back then, the state education standards we now take for granted had not become common. In short, both supporters and opponents of such legislation took it for granted that legislatures had the power to mandate general-education requirements. Such debate as there was (and there was virtually no debate because the bills easily passed) turned on whether legislating curriculum was wise. Although the concept of academic freedom was familiar by the 1920s, no academic or legal elites raised objections to legislative general-education mandates on academic-freedom grounds. On the contrary, the vast majority of academic and legal elites in the 1920s wanted new curriculum requirements legislated.

It’s true that S.B. 226 provides more detailed direction on topical coverage than most previous state-level general-education laws. Utah’s experience, however, provides the best argument for this more directive approach. The Utah legislature has already mandated that all students graduating from public universities “demonstrate a reasonable understanding of the history, principles, and economic system of the United States.” As John Sailer has shown, however, in a report for the National Association of Scholars (summarized here), a number of public universities in Utah have abused or evaded this legislative requirement. Weber State University, for example, allows the requirement to be satisfied by courses on “The LGBTQ Experience,” “The Black Experience,” or “The Latinx Experience.”

Sailer recommends both more requirements and more detailed and directive legislative language to help deter this kind of evasion. That’s exactly what S.B. 226 provides by mandating, for example, a “broad survey” course on American history that covers issues of “politics, economics, technological progress, war, and foreign policy,” with similar topical detail for other required courses. More important, S.B. 226 provides for a new school of general education with a faculty truly expert in, and committed to, the classic approach.

Utah state senator and senate education committee chairman John Johnson is sponsoring S.B. 226. Last year, Johnson helped kick off the move to ban DEI training, mandatory faculty statements, and other DEI initiatives at public universities. Johnson helped move a rewritten DEI-ban bill to final passage earlier this year. As an economist who served as professor and chair of the management and information systems department at the John M. Huntsman School of Business at Utah State University, Johnson knows whereof he speaks. He’s had a business career but has also spent considerable time in academia. Few state education committee chairs have that depth of experience.

Some might wonder whether students nowadays can handle the demands of a traditional general-education curriculum. The answer to that can be found in a just-published piece by the very liberal University of Chicago professor Martha Nussbaum. Nussbaum tells the story of her 2023 trip to Utah Valley University, a public open-enrollment school, to lecture in the philosophy course required of all undergraduates. Nussbaum was stunned by the quality and attentiveness of the students. She calls her visit to Utah “one of the most heartening scenes in higher education that I have ever witnessed.” To Nussbaum, the point is that legislatures should keep supporting the humanities. I would add that undergraduates at every sort of public university, from elite to nonselective, can handle and even thrive on demanding general-education requirements. What’s more, liberals as well as conservatives will approve of such courses. This was true through most of the 20th century, when institutions from prestigious Ivies to local community colleges embraced traditional general education — with the programs supported by faculty from across the political spectrum.

And maybe something else stands behind Nussbaum’s story. Utah has a long tradition of education that I’m just myself learning more about. There’s a bit of Latter-Day Saints scripture that’s widely quoted in Utah by the public in general, and by advocates of classical and university education in particular: “Seek ye of the best books words of wisdom.” If Nussbaum’s experience is any indication, the admonition has worked. It’s tough to imagine anything more perfectly designed to carry on the “best books” legacy than Senator John Johnson’s S.B. 226. And the legacy of this bill will likely be national, not simply statewide. If this bill advances in even one state, it will likely spread further, marking Utah as the new national leader in the reform and restoration of American higher education. Stay tuned.

Stanley Kurtz is a Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. Beyond his work with Education and American Ideals, Mr. Kurtz is a key contributor to American public debates on a wide range of issues from K–12 and higher education reform, to the challenges of democratization abroad, to urban-suburban policies, to the shaping of the American left’s agenda. Mr. Kurtz has written on these and other issues for various journals, particularly National Review Online (where he is a contributing editor).