Published June 20, 2022

What does it mean to be a conservative in a time of profound upheaval, when it is no longer clear what can or even should be conserved? How can the conservative remain loyal to both his nation and his government when the highest offices in the land are filled by those who voice open contempt for the values of the American people?

In the wake of the apocalyptic events of 2016 and 2020, conservatives are in danger of fragmenting into warring tribes, with some calling for moderation while others push for revolution. To be sure, conservatives have traditionally extolled the value of the maxim festina lente — ”make haste slowly” — and cautioned against the dangers of acting precipitately. And yet, since no one loves the inherited goods of community, faith, and custom as dearly as the conservative, no one is liable to fight more fiercely when they are under mortal threat.

The challenges we face today, grim as though they may be, are not fundamentally new. Among the statesmen who brought our nation into being were those committed to the defense of traditional laws and liberties in the face of mounting oppression by out-of-touch authorities who held their very way of life in contempt. But the defense of tradition against abusive authority is an exceedingly tricky business, liable to end in the loss of both tradition and authority. The American Revolution itself could have easily degenerated into anarchic tribalism or culminated in the exchange of one foreign oppressor for another.

The fact that it did not was the achievement of a kind of far-sighted and moderate statesmanship that conservatives must recover if we are to have a chance of steering our way through one of the great crises of our republic. To this end, few exemplars of the founding era have more to teach us than John Jay — a man who modeled throughout his remarkable life and work the vocation of a conservative in a time of revolution.

A LIFE IN THE SPOTLIGHT

Jay was born in 1745 in New York City, then a bustling merchant town of 11,000. Even as duty would call him first to the center of continental affairs in Philadelphia and then to the great power centers of Europe — Madrid, Paris, and London — he would remain closely tethered to this hometown for most of his life. Wherever Jay traveled, and whatever task he shouldered, his heart remained in New York — the city and state to which he would dedicate extraordinary labors.

Jay attended King’s College (later Columbia) in Manhattan. By 1774, he was one of the most prosperous lawyers in the colony. His talents quickly catapulted him to the forefront of governing affairs as a New York delegate to the First and Second Continental Congress. In 1776, he returned to New York as one of the key members of its committee to establish a new state constitution, and shortly thereafter he served as the state’s first chief justice. In that epochal year, in which bold dreams of independence clashed with the disheartening realities of invasion and military defeat, Jay rallied the flagging spirits of his countrymen with An Address of the Convention of the Representatives of the State of New York to Their Constituents — one of the most stirring and powerful statements of patriotic determination the war produced.

Barely a decade later, in 1787 and 1788, he stood shoulder to shoulder with Alexander Hamilton in the herculean task of securing ratification of the new U.S. Constitution in New York — the state with the largest and best organized Anti-Federalist cohort. He would later run for governor of the state, first unsuccessfully in 1792 but then successfully for two three-year terms beginning in 1795. His years of retirement were spent near Bedford, just northeast of New York City. At his death in 1829, the New York Bar Association declared 30 days of mourning to honor one whose “patriotism,” “great talents as a statesman,” “great acquirements as a jurist,” “eminent piety as a Christian,” and “probity as a man, all unite to present him to the public as an example whose radiance points to the attainment of excellence.”

Despite the intimate bonds that attached him to his hometown and state, Jay’s horizons were vastly wider than most of his contemporaries’. From relatively early in the Revolutionary War, Jay displayed a broad continental perspective, perceiving keenly the abundant potential of America as an independent nation:

Extensive wildernesses, now scarcely known or explored, remain yet to be cultivated, and vast lakes and rivers, whose waters have for ages rolled in silence and obscurity to the ocean, are yet to hear the din of industry, become subservient to commerce, and boast delightful villas, gilded spires, and spacious cities rising on their banks.

More than perhaps any founder (with the possible exception of his friend Hamilton), Jay worked tirelessly to promote a sense of national identity among his often stubbornly provincial and narrow-minded compatriots. His Federalist No. 2 is justly famous as a classic statement of early American nationalism, but it merely gave voice to convictions that had peppered Jay’s letters for years. In 1783 he wrote to Gouverneur Morris, “no time is to be lost in raising and maintaining a national spirit in America.” And from the beginning, he recognized that such a national spirit would require an effective national government.

When this government was formed, few men were as well equipped as Jay to help lead it. From 1774 onward, he had played a leading role in the struggle for a new nation. At the First Continental Congress, he penned the eloquent Address to the People of Great Britain, which contained the powerful statement of the colonies’ grievances and their understanding of America’s role in the conflict — that is, the guardian of historic British liberties that the increasingly arbitrary government in Whitehall was seeking to uproot throughout the empire. In 1775, this acknowledged master of English prose was called on again to write Congress’s Letter to the Oppressed Inhabitants of Canada, exhorting them to share in the struggle for liberty.

After his work in New York, Jay was summoned back to Congress in 1778 and soon elected president of the Continental Congress. A year later, he was dispatched on his first diplomatic mission as minister plenipotentiary to Spain, and in 1782, he was transferred to Paris to help lead American peace negotiations with Britain. The resulting Treaty of Paris, which historian Joseph Ellis calls “the greatest triumph in the annals of American diplomacy,” was masterminded by Jay who, though the youngest member of America’s three-man negotiating team, displayed the foresight, courage, and keen sense of national honor that earned him “the principal merit” for the achievement in the eyes of his colleague John Adams — never one quick to concede such merit to his rivals.

On returning to America in 1784, he was conscripted into the most important role in the Confederation Congress — the secretary for foreign affairs — and upon the dissolution of that Congress in 1788, George Washington named him chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Crucial as this role was for securing the foundations of constitutional government, Washington called Jay away from it in 1794 for another critical diplomatic assignment — this time as envoy extraordinary to Great Britain — to prevent America from being drawn into the international conflagration of war unleashed by the French Revolution. The resulting Jay Treaty of 1794, though fiercely maligned by opponents who still despised their former mother country and desired a close alliance with France, was a scarcely less significant diplomatic achievement than the 1783 treaty, gaining America the breathing room to stand on her own as a young nation among the great powers of the world.

Given Jay’s lifelong record of service as one of the chief architects of the American nation, it is all the more remarkable that he was an extremely reluctant revolutionary — one who fought hard for peaceful conciliation at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War, and who held out longest against the Declaration of Independence. Yet when convinced that war was unavoidable, he threw himself into the cause with complete dedication. His remarks in a letter nearly 20 years later, delivered while negotiating the Jay Treaty, sum up well his posture on the subject:

We live in an eventful season. We have nothing to do but our duty, and one part of it is to prepare for every event. Let us preserve peace while it can be done with propriety; and if in that we fail, let us wage war, — not in newspapers, and impotent sarcasms, but with manly firmness, and unanimous and vigorous efforts.

Once he committed himself, Jay never wavered in his faith that from this struggle would arise a new nation that would extend and enrich the legacy of England’s Protestant liberty across the vast expanse of a new continent.

Indeed, there were few patriots who felt as keenly as did Jay a sense of continuity between America’s British colonial past and her independent national future. Although himself of French Huguenot stock, Jay always treasured the British heritage in America and the legacy of laws and political institutions it had bequeathed to the young republic. As he wrote to a newspaperman in 1796, “[i]t certainly is chiefly owing to institutions, laws, and principles of policy and government, originally derived to us as British colonists, that, with the favour of Heaven, the people of this country are what they are.” And yet, despite the frequent accusations of Anglophilia leveled by his opponents, Jay also understood the importance of America being able to hold her head high not as a nation in name only, but as one ready to chart her own course and earn the grudging respect of the Old World potentates.

With this introduction to Jay in hand, let us turn to consider key elements of his conservative, nationalist statesmanship. First, we shall look at Jay’s understanding of the American Revolution, and his determination to maintain as much continuity as possible in the midst of the break with Britain. We will then examine his role in the formation of the new republic, in which he sought to instill in his fellow citizens a dual commitment to law and liberty, thereby resisting the libertinism of radical democracy that the Revolution had unleashed in parts of America. Finally, we will see how Jay’s foreign policy sought to make good on America’s claim to independence, recognizing the shared interests and culture that continued to unite America and Britain while insisting that America never forfeit her freedom or sacrifice her distinctive interests to those of any other nation.

A RELUCTANT REVOLUTIONARY

When Jay arrived in Philadelphia in September 1774, he was eager neither for war nor for American independence. The situation was critical, to be sure. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 had been followed by the Intolerable Acts, whereby Parliament had shut down the port of Boston and imposed martial law, thus depriving Massachusetts citizens of many of their ordinary rights as Englishmen. Hard on the heels of this measure, the 1774 Quebec Act alarmed the colonists still further — especially arch-Protestants like Jay, who saw a sinister connection between its quasi-establishment of Roman Catholicism in Canada and its mimicry of “popish” forms of arbitrary power that the French had used in their colonial administration. Agitation spread throughout all the colonies as a result, prompting representatives to assemble in Philadelphia to make common cause against this expanding tyranny.

Some of the delegates, to be sure, had more radical ideas. The fire-breathing Patrick Henry of Virginia declared his view that “government is at an end,” and that “[a]ll America is thrown into one mass.” But Jay demurred: “The Measure of Arbitrary power,” he asserted, “is not full, and I think it must run over, before We undertake to frame a new constitution.”

While continuing to debate concrete measures, Congress agreed on the importance of a forceful petition to the mother country. Despite his youth (he was then 28), Jay was selected as chief author of this Address to the People of Great Britain — a document that not only powerfully summarized the American cause at this date, but gave us a valuable window into Jay’s conservative thinking.

Here, Jay repeatedly expressed the American people’s sense of shared identity with the British and their belief in all that the British Empire had historically stood for:

In almost every age, in repeated conflicts, in long and bloody wars, as well civil as foreign, against many and powerful nations, against the open assaults of enemies, and the more dangerous treachery of friends, have the inhabitants of your island, your great and glorious ancestors, maintained their independence and transmitted the rights of men, and the blessings of liberty to you their posterity.

The Americans, wrote Jay, were “descended from the same common ancestors” as the English; their “forefathers participated in all the rights, the liberties, and the constitution, you so justly boast of, and…have carefully conveyed the same fair inheritance to us.” Thus it was not simply their right, but their obligation to stand up on behalf of this inheritance of liberty — and not only on their own behalf, but to protect liberty in Britain, lest the corrupt ministry, “by having our lives and property in their power…may with the greater facility enslave you.”

From Jay’s perspective, The American grievances revolved around two chief issues. The first was the abridgment of traditional English liberties and legal procedures. This had begun with Parliament’s usurpation of the power of taxation but had escalated dramatically with the more recent Intolerable Acts, which had infringed one of the most sacred English traditions: trial by jury of one’s peers. “By the course of our law,” wrote Jay, “offences committed in such of the British dominions in which courts are established and justice duely and regularly administered, shall be there tried by a jury of the vicinage.” Under the Intolerable Acts, by contrast, offenders were “to be taken by force, together with all such persons as may be pointed out as witnesses, and carried to England, there to be tried in a distant land, by a jury of strangers.”

The occasion for these draconian measures had been the Boston Tea Party. Jay, parting ways with more radical patriots, had deplored such lawlessness, and in the address he tacitly conceded that the perpetrators were probably liable to legal action. Rather than following due process of law, however, the English ministry had enacted summary punishment on the whole city of Boston, “involving the innocent in one common punishment with the guilty, and for the act of thirty or forty, to bring poverty, distress and calamity on thirty thousand souls, and those not your enemies, but your friends, brethren, and fellow subjects.”

If this weren’t alarming enough, there was the Quebec Act to consider. As the descendant of fleeing Huguenots, Jay still perceived the world very much through the lens of British Protestant liberty against French Catholic tyranny, and saw the qualified establishment of Catholicism and French civil law in Canada as proof that Whitehall had fallen prey to popish impulses. The colonists’ neighbors to the north, he fulminated,

are now the subjects of an arbitrary government, deprived of trial by jury, and when imprisoned, cannot claim the benefit of the habeas corpus act, that great bulwark and palladium of English liberty. Nor can we suppress our astonishment that a British Parliament should ever consent to establish in that country a religion that has deluged your island in blood, and dispersed impiety, bigotry, persecution, murder, and rebellion, through every part of the world.

Along with many of his fellow colonists, Jay saw the Quebec Act as the tip of a spear that was set “to reduce the ancient free Protestant Colonies to the same state of slavery” as the French-Canadians.

The obvious solution to Jay at this point was not independence, but greater union. The ministry’s strategy, he argued, was to divide and conquer, meaning the free peoples of Great Britain and America would have to band together in defense of their ancient rights. “[T]ake care,” the Address warned complacent Englishmen, “that you do not fall into the pit that is preparing for us.” It concluded with a ringing denial that America harbored separatist ambitions:

You have been told that we are seditious, impatient of government and desirous of independency. Be assured that these are not facts, but calumnies. — Permit us to be as free as yourselves, and we shall ever esteem a union with you to be our greatest glory and our greatest happiness, we shall ever be ready to contribute all in our power to the welfare of the Empire — we shall consider your enemies as our enemies, and your interest as our own.

Jay was wholly sincere in this protestation against a desire for independence. During the Second Continental Congress the following year, he helped draft another petition that sought earnestly to avoid a permanent break with Britain even after the outbreak of war, conceding the traditional “[r]ight of the British Parliament to regulate the Commercial Concerns of the Empire.” In comparing this draft with the final version penned by John Dickinson, Jay’s biographer notes that he “was more conciliatory than even the member of Congress known as the leader of the conciliators.” Jay remained staunchly opposed to any talk of independence as late as April 1776, and called the claim that Congress was considering it “an ungenerous and groundless charge.”

Nearly 50 years later, having done more than perhaps anyone aside from Washington and Adams to make American independence a reality, Jay was still adamant that Americans had not sought independence, but had rather had it forced upon them. Replying to a letter from George Otis of Quincy, Massachusetts, about a recently published history of the Revolutionary War by the Italian historian Carlo Botta, Jay took umbrage at Botta’s claim that Congress’s “real object” all along was independence. On the contrary, he argued:

Explicit professions and assurances of allegiance and loyalty to the sovereign…and of affection for the mother country, abound in the journals of the colonial Legislatures, and of the Congresses and Conventions, from early periods to the second petition of Congress in 1775. If these professions and assurances were sincere, they afford evidence more than sufficient to invalidate the charge of our desiring and aiming at independence.

Otis replied that he had shared Jay’s remarks with Adams, who warmly concurred. “For my own part,” Adams had remarked, “there was not a moment during the Revolution when I would not have given everything I possessed for a restoration to the state of things before the contest began, provided we could have had a sufficient security for its continuance.”

Elsewhere, Jay argued that America had not fought to gain independence so much as to maintain it. In a revealing letter to the Reverend Samuel Miller in 1800, Jay objected to a phrase Miller had used during his funeral sermon for Washington:

Writing thus freely, I think it candid to observe that in some instances ideas are conveyed which do not appear to me to be correct; such, for instance, as “our glorious emancipation from Britain.” The Congress of 1774 and 1775, etc., regarded the people of this country as being free; and such was their opinion of the liberty we enjoyed so late as the year 1763, that they declared the colonies would be satisfied on being replaced in the political situation in which they then were. It was not until after the year 1763 that Britain attempted to subject us to arbitrary domination….Thus we became a distinct nation, and I think truth will justify our indulging the pride of saying that we and our ancestors have kept our necks free from yokes, and that the term emancipation is not applicable to us.

From Jay’s perspective, the purpose of the struggle had been to return America and Britain to the status quo of 1763; only Britain’s needless aggression had forced America to declare independence and take control of her own destiny.

BUILDING A NEW NATION

On Jay’s reading, then, the American colonists had initially sought independence not as a good in itself, as it was for radicals like Thomas Paine, but as a means of upholding the traditional laws that served as the bulwark of American liberty. Once the colonies went their separate way in 1776, Jay threw himself enthusiastically into the fight to defend the independence thus declared.

Even then, however, he remained convinced that the preservation of American liberty depended not on abstract ideals or high-minded paeans to the innate goodness of the nation’s people, but on the rule of law. Americans, he often observed, were equally capable of “great virtues, and of many great and little vices.” “Which will predominate,” he wrote to Washington in 1779, “is a question which events not yet produced nor now to be discerned can alone determine,” and its answer would depend not on mere good intentions, but on effective government. “The dissolution of our government,” Jay observed, “threw us into a political chaos. Time, wisdom, and perseverance will reduce it into form, and give it strength, order, and harmony.”

As the Confederation Congress languished in increasing impotence seven years later, he was less optimistic, confessing himself “uneasy and apprehensive; more so than during the war.” “The mass of men,” he lamented,

are neither wise nor good, and the virtue like the other resources of a country, can only be drawn to a point and exerted by strong circumstances ably managed, or a strong government ably administered. New governments have not the aid of habit and hereditary respect, and being generally the result of preceding tumult and confusion, do not immediately acquire stability or strength.

Too many rabble-rousers in revolutionary America, operating on the thoroughly nonsensical maxim “that government is best which governs least,” had tried to sell the American people on the idea that theirs was a revolution not simply against arbitrary or distant government, but against government as such. In one letter to a friend as Shays’s Rebellion was unfolding in late 1786, Jay declared, “[i]t is time for our people to distinguish more accurately than they seem to do between liberty and licentiousness. The late revolution would lose much of its glory, as well as utility, if our conduct should confirm the tory maxim, ‘That men are incapable of governing themselves.'”

Jay knew history and human nature well enough to recognize that too much assertion of liberty could easily produce its opposite. As he wrote to Thomas Jefferson around the same time, “the charms of liberty will daily fade” for well-intentioned Americans upon seeing the disorder of the new republic,

and in seeking for peace and security, they will too naturally turn towards systems in direct opposition to those which oppress and disquiet them. If faction should long bear down law and government, tyranny may raise its head, or the more sober part of the people may even think of a king.

Jay would later voice similar sentiments in his 1788 Address to the People of the State of New York — generally hailed as the most important contribution to the great debate over New York’s ratification of the Constitution.

Such a turn from liberty to security was precisely the sequence that soon unfolded in France — a revolution that Jay, unlike Jefferson, was wary of from the beginning. In his first letter on the subject in December 1789, Jay granted that the French Revolution certainly “promises much,” and expressed hope it would deliver on that promise. However, he maintained that “there are many nations not yet ripe for liberty, and I fear that even France has some lessons to learn, and perhaps, to pay for on the subject of free government.” To a French correspondent a few months later, Jay offered the Burkean admonition (before Edmund Burke wrote his famous Reflections on the Revolution in France): “The natural propensity in mankind of passing from one extreme too far towards the opposite one sometimes leads me to apprehend that may be the case with your national assembly.” By 1796, while Jeffersonians still defended France and celebrated her achievements for liberty, Jay observed that the latter stage of the revolution “had, in my eye, more the appearance of a woe than a blessing. It has caused torrents of blood and of tears, and been marked in its progress by atrocities very injurious to the cause of liberty and offensive to morality and humanity.”

That the American Revolution did not follow the same destructive course was due in no small part to Jay’s tireless efforts to instill a respect for the rule of law in his restless compatriots. As an eminent lawyer in pre-revolutionary America, Jay found himself elevated first to chief justice of New York and later to chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In these roles, Jay was not merely called upon to hear cases, but play an important role as an educator, instructing the American people in the art of self-government through the regular charges to grand juries he was called upon to give when overseeing circuit courts. On his first circuit as Supreme Court justice in March 1790, Jay offered a powerful summary of his political philosophy in his charge to the jurors:

It cannot be too strongly impressed on the minds of us all how greatly our individual prosperity depends on our national prosperity, and how greatly our national prosperity depends on a well organized, vigorous government, ruling by wise and equal laws, faithfully executed; nor is such a government unfriendly to liberty — to that liberty which is really inestimable; on the contrary, nothing but a strong government of laws irresistibly bearing down arbitrary power and licentiousness can defend it against those two formidable enemies. Let it be remembered that civil liberty consists not in a right to every man to do just what he pleases, but it consists in an equal right to all the citizens to have, enjoy, and to do, in peace, security, and without molestation, whatever the equal and constitutional laws of the country admit to be consistent with the public good.

All the key elements of Jay’s Federalist perspective are here: the close connection between individual and national prosperity, the need for a vigorous government to act as a safeguard of liberty, and the vast difference between libertarianism and the ordered liberty that rests on laws enacted by the people.

Jay, of course, knew better than to simply equate the “rule of law” with “the will of the people” the way Maximilien Robespierre or Jefferson would. In the early years of the Revolution, many Americans imagined all that was needed for free government was a representative legislature by which the people would rule themselves according to laws of their own making. Accordingly, many of the early state constitutions vested nearly all political authority in state legislatures, with governors and judges stripped of much of their power. For Jay, however, the value and authority of law lay in its ability not merely to express the will of the people, but to reconcile this with the people’s past identity as well as their future interests. An untrammeled legislature, he believed, would be liable to reverse laws almost as soon as they were enacted, and to pass laws that undermined traditional liberties or disastrously compromised long-term interests. To anchor present lawmaking in the soil of the past, and to prevent short-sighted decisions from undermining long-term prosperity, Jay recognized that a strong executive and independent judiciary were also necessary.

Consequently, Jay fought to make the New York constitution the most conservative of the original U.S. state constitutions, with a strong governor and a Council of Revision that could veto rash legislation. He served on this council as the first chief justice of New York, repeatedly seeking to restrain the state legislature’s actions against suspected Tories that violated hallowed principles of English common law. As Congress’s secretary for foreign affairs in the years following the war, he would fight a similarly thankless battle against the petty and vindictive state legislatures that systematically undermined the hard-earned Treaty of Paris and all received principles of international law by their continued persecution of Tories and refusal to pay debts due to British creditors. These experiences led Jay, in the lead-up to the Constitutional Convention, to champion a new federal government that would tie the national legislature to a strong and independent executive branch, along with a national judiciary able to articulate the “supreme law of the land.”

AMERICA AMONG THE NATIONS

Given Jay’s professed regard for the English constitution and common law, as well as his early reticence to accept a break with the mother country, it should come as little surprise that he was dogged throughout his career by charges of excessive Anglophilia. Particularly in the aftermath of the controversial Jay Treaty of 1794, which secured American neutrality in the war raging between Britain and France, Jay was loudly denounced for his slavish dependence on Great Britain.

Yet few leaders of the founding era worked so tirelessly to give real substance to America’s claim of independence. Fewer still articulated so clearly and consistently a foreign policy of American nationalism and self-determination. The problem was that for the first few decades of American nationhood, many of Jay’s compatriots had allowed their hostility toward their former British masters to cloud their judgment, driving them into an alliance with France that threatened to become a bondage little better than the one they had escaped.

From the beginning of the French alliance in 1778, Jay worried about the mismatch between America — with her Protestant religion, common law, and representative institutions — and France, with its Catholicism, civil law, and absolutism. He confided to his friend Gouverneur Morris in 1778, “[w]hat the French treaty may be, I know not. If Britain would acknowledge our independence, and enter into a liberal alliance with us, I should prefer a connexion with her to a league with any power on earth.”

Before long, however, he came to accept that America not only desperately needed French aid, but had pledged her national honor to that alliance. With this in mind, he determined that America should remain faithful to France — but only as far as honor strictly dictated. In due course, he would come to deplore the idea of entering into entangling alliances altogether.

Sent to Madrid to negotiate an alliance with Spain — which had recently entered the war against Britain for its own purposes — in 1779, Jay quickly grasped that Spain had little interest in advancing the cause of American independence; instead, it meant to use the Americans as a tool against Britain while keeping her as weak as possible. Particularly vexing was Spain’s determination to stake a claim to most of the lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi — lands the new American states were already counting on settling. Forced to fritter away two years in pointless negotiations — and, by Congress’s improvidence, left humiliatingly dependent on stingy Spanish financial aid — Jay departed Madrid in 1782 thoroughly disillusioned about the realities of European power politics.

Having learned this lesson, he arrived in Paris for peace talks with a sharp nose for detecting duplicity, and soon sensed that behind their generous façade, the French ministers were every bit as cynical in their dealings with the idealistic young republic as Spain had been. They supported Spain’s territorial aspirations east of the Mississippi and admonished Jay that America’s claims in that direction were delusional. When the British peace commission offered to negotiate with “the American colonies” — tacitly denying American independence — Jay protested, but the Comte de Vergennes (the French foreign minister) sided with the British commissioners, advising Jay that it was foolish to expect Britain to recognize the colonies’ independence until the treaty was signed.

Jay determined that the only way for America to secure her real independence over the long run was to forthrightly assert it from the outset. The situation was extremely awkward, however, for Congress — skillfully manipulated and liberally bribed by the French ambassador — had sent its peace commissioners humiliating instructions to “undertake nothing…without [the French’s] knowledge and concurrence; and ultimately to govern [themselves] by [France’s] knowledge and concurrence.”

Benjamin Franklin, Jay’s fellow commissioner and senior American diplomat in Europe, felt that Jay was being unnecessarily paranoid and advised him not to rock the boat with the French. In a climactic carriage ride back from Versailles, however, Jay forcefully argued his case, ultimately convincing Franklin to defy Congress’s instructions and shut the French out of the negotiations. Summarizing his reasoning in a dispatch to Robert Livingston, the U.S. secretary for foreign affairs, he wrote:

[The French] are interested in separating us from Great Britain, and, on that point we may, I believe, depend upon them; but it is not their interest that we should become a great and formidable people, and therefore they will not help us to become so.

It is not their interest that such a treaty should be formed between us and Britain, as would produce cordiality and mutual confidence. They will, therefore, endeavor to plant such seeds of jealousy, discontent, and discord in it as may naturally and perpetually keep our eyes fixed on France for security. This consideration must induce them to wish to render Britain formidable in our neighborhood, and to leave us as few resources of wealth and power as possible.

From this, he concluded:

I think we have no rational dependence except on God and ourselves….[I]f we lean on [France’s] love of liberty, her affection for America, or her disinterested magnanimity, we shall lean on a broken reed, that will sooner or later pierce our hands.

Though Livingston was furious when he received this dispatch, so slow were North Atlantic communications in those days that by the time his rebuke reached Jay, the treaty had been signed for months — an agreement that historians consider “the greatest triumph in the annals of American diplomacy.” For decades thereafter, even Jay’s detractors had to grudgingly concede that the Treaty of Paris was remarkably beneficial for American interests. And though they argued that he had simply lucked out while taking foolish risks that unnecessarily alienated America’s well-intentioned French allies, modern archival research has demonstrated that Jay was uncannily correct in his surmises of French intentions: Vergennes had in fact sought to delay Britain’s recognition of American independence as long as possible to keep America in the war until France and Spain achieved their own expansionist war aims; he had attempted to limit American territorial, fishing, and trade privileges to keep her weak; and he had hoped to prevent any real rapprochement between the two nations so that the Americans would remain dependent on France for decades to come.

Jay’s suspicion of France, however, did not entail naïveté toward Britain. “If they again thought they could conquer us,” he had written to Livingston, “they would again attempt it.” The key, Jay realized, was to rely on no one’s benevolence: Americans must “be as independent on the charity of our friends, as on the mercy of our enemies.” For Jay, sound foreign policy involved seeking to establish a long-term alignment of interests while maintaining a strong military that would deter greedy European powers. As he wrote to Adams in the midst of the Paris negotiations, “[w]ar must make peace for us, and we shall always find well appointed armies to be our ablest negotiators.”

However, Jay also believed that once Britain had abandoned any claims to lordship over America, the estranged mother and daughter would find in their common culture a basis for lasting friendship. It was upon this conviction, which Washington and Hamilton shared, that he sailed to London in 1794 to prevent America from being drawn into the new European war on the side of revolutionary France. Despite attempts of Francophiles in America to scuttle the détente, Jay succeeded once again in negotiating a durable and advantageous peace settlement — in part because he found his earlier hopes for a resurgent fellow feeling between Americans and the British richly repaid. “The idea which everywhere prevails,” he wrote to Washington, “is that the quarrel between Britain and America was a family quarrel, and that it is time it should be made up. For my part, I am for making it up, and for cherishing this disposition on their part by justice, benevolence, and good manners on ours.” But this did not mean he believed America should slavishly attach herself to Britain any more than to France: “To cast ourselves into the arms of this or any other nation,” he observed, “would be degrading, injurious, and puerile; nor, in my opinion, ought we to have any political connection with any foreign power.”

Here, as elsewhere in his political career, Jay was a shrewd pragmatist. Yet he also acted on the basis of deep-seated principles. In this case the principle was his commitment to the idea, derived from Swiss political theorist Emer de Vattel, of the equality and independence of all nations. His claims on behalf of American independence were not cynical ploys to enable America to export her revolutionary ideas to the rest of the world, but a reflection of a foreign-policy application of the Golden Rule: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” As he put it in a 1793 speech:

In like manner the nations throughout the world are like so many great families placed by Providence on the earth, who having divided it between them, remain perfectly distinct from and independent of each other. Between them there is no judge but the great Judge of all. They have a perfect right to establish such governments and build such houses as they prefer, and their neighbors have no right to pull down either because not fashioned according to their ideas of perfection; in a word, one has no right to interfere in the affairs of another, but all are bound to behave to each other with respect, with justice, with benevolence, and with good faith.

Throughout the 1790s, Jay firmly maintained this principle of non-interference in the face of strong Democratic-Republican pressure pushing America to join her former French ally in a glorious fight for republican freedom throughout Europe. He simultaneously resisted equally strong pressure from some of his Federalist allies, who wished America to support Britain openly against the bloodthirsty revolutionaries. Drafting a proclamation of neutrality in 1793 at the request of Washington and Hamilton, he wrote:

[A]lthough certain circumstances have attended that revolution, which are greatly to be regretted, yet the United States as a nation have no right to decide on measures which regard only the internal and domestic affairs of others. They who actually administer the government of any nation are by foreign nations to be regarded as its lawful rulers so long as they continue to be recognized and obeyed by the great body of their people.

Thus, inasmuch as the various French revolutionary administrations broadly commanded the consent of the French nation, Jay insisted that America must recognize them and deal respectfully with them. However, inasmuch as the revolutionaries sought to export their ideals to the rest of Europe by force of arms, America could have nothing to do with such imperialism. Writing in 1796 to a British friend who was naively enthusiastic about French revolutionary ideals, Jay observed:

I should not think that man wise who should employ his time in endeavouring to contrive a shoe that would fit every foot; and they do not appear to me much more wise who expect to devise a government that would suit every nation. I have no objections to men’s mending or changing their own shoes, but I object to their insisting on my mending or changing mine. I am content that little men should be as free as big ones and have and enjoy the same rights; but nothing strikes me as more absurd than projects to stretch little men into big ones, or shrink big men into little ones. Liberty and reformation may run mad, and madness of any kind is no blessing.

In short, he concluded, “[w]e must take men and things as they are, and act accordingly — that is, circumspectly.”

A CONSERVATIVE LIFE

While Jay’s conservative principles, articulated over a lifetime of public service and private correspondence, are eloquent and instructive, they are hardly unique: History has seen many men of high-minded conservatism who proved to be woefully inadequate statesmen — prone to erratic outbursts, short-sighted decisions, and tactless actions that alienated important associates. Jay’s friends and close political allies Adams and Hamilton fit this description in some measure: Though they were indispensable leaders of the early republic, both struggled to control their fierce pride and fiery tempers, and both suffered disastrous lapses of judgment, precipitating a fateful split within the Federalist Party and threatening the foundations of the young nation. What made Jay such an exemplary and successful statesman (albeit one unlikely to ever have a hit musical named after him) was his ability to practice what he preached: Jay embodied his conservatism in his personal life.

When Jay wrote about the necessity for America to learn the restraint and moderation of self-government, he spoke from personal experience. At a critical point in his career, he was stymied by brazen election fraud that deprived him of the New York governorship. His friends urged him to fight back with every means at his disposal, but Jay refused, calmly reassuring his agitated wife, “[h]aving nothing to reproach myself with in relation to this event, it shall neither discompose my temper, nor postpone my sleep. A few years more will put us all in the dust; and it will then be of more importance to me to have governed myself than to have governed the State.”

Although a stickler for America’s national honor during negotiations of the Treaty of Paris and throughout his diplomatic career, Jay recognized, as Adams and Hamilton never quite could, that protecting the nation’s honor might require its representatives to submit to dishonor with equanimity. Greeted in America after the Jay Treaty with a storm of scurrilous criticism, Jay remained unflappable:

Be that as it may, I shall continue to possess my mind in peace, and be prepared to meet with composure and fortitude whatever evils may result to me from the faithful discharge of my duty to my country. The history of Greece, and other less ancient governments, is not unknown to either of us; nor are we ignorant of what patriots have suffered from domestic factions and foreign intrigues in almost every age.

Faced with the maddeningly slow progress of justice and good government, even on so morally urgent an issue as the abolition of slavery, Jay exhibited a profound patience, convinced that the justice of God would overcome the machinations of evil men in due time:

The wise and the good never form the majority of any large society, and it seldom happens that their measures are uniformly adopted, or that they can always prevent being overborne themselves by the strong and almost never-ceasing union of the wicked and the weak. These circumstances tell us to be patient, and to moderate those sanguine expectations which warm and good hearts often mislead even wise heads to entertain on those subjects. All that the best men can do is, to persevere in doing their duty to their country, and leave the consequences to Him who made it their duty; being neither elated by success, however great, nor discouraged by disappointments however frequent and mortifying.

Many political leaders tend to veer between extremes of idealism and cynicism, placing their faith in utopian schemes for human improvement or despairing of achieving anything except by the most self-interested Realpolitik. Jay avoided both ditches throughout his career. As a devout Anglican, he took human frailty and corruption very seriously: In the first letter we have preserved from his pen (written at the tender age of 20), he observed, “[t]he ways of men, you know, are as circular as the orbit through which our planet moves, and the centre to which they gravitate is self: round this we move in mystic measures, dancing to every tune that is loudest played by heaven or hell.” And throughout his decades of public service, Jay never lost this healthy sense of realism, which gave him an uncanny ability to judge motives and predict behaviors.

At the same time, while he had little faith in people, he had a great deal of faith in his God. Over and over in his letters and public statements, Jay expressed a profound and serene faith that God was in control, and that he would ensure the final success of the American cause. At one of the darkest hours of the war, when the Continental currency was collapsing and the Continental Army languished unpaid and ill-equipped, he could write to his countrymen:

And can there be any reason to apprehend that the Divine Disposer of human events, after having separated us from the house of bondage, and led us safe through a sea of blood towards the land of liberty and promise, will leave the work of our political redemption unfinished, and either permit us to perish in a wilderness of difficulties, or suffer us to be carried back in chains to that country of oppression, from whose tyranny he hath mercifully delivered us with a stretched-out arm?

Thus it was that, amid the tumult and wreckage of the election of 1800, when his fellow Federalists were convinced that “an Atheist in Religion and a Fanatic in politics” had seized “the helm of the State” and was about to drive the young nation aground, Jay could stand as an anchor of calm in the storm. Although he had the power as governor of all-important New York to defy the popular vote and appoint a slate of Federalist electors that would deny Jefferson the presidency, he knew well that what was technically legal was not necessarily honorable, and that what was dishonorable could never be truly expedient.

Jay used his weighty influence to reconcile his fellow Federalists to this unhappy election result, ensuring that the first real transfer of power in American history would be a peaceful one. In so doing, he safeguarded the still-fragile bonds of national unity that he had fought so hard to forge in his many roles over the previous quarter-century.

As conservatives today confront unhappy election results, along with rampant atheism and fanaticism in the halls of power, it’s time they learned anew from John Jay’s serene confidence and tireless labors to give a fractured nation a new lease on life.

Brad Littlejohn, Ph.D., is a Fellow in EPPC’s Evangelicals in Civic Life Program, where his work focuses on helping public leaders understand the intellectual and historical foundations of our current breakdown of public trust, social cohesion, and sound governance. His research investigates shifting understandings of the nature of freedom and authority, and how a more full-orbed conception of freedom, rooted in the Christian tradition, can inform policy that respects both the dignity of the individual and the urgency of the common good. He also serves as President of the Davenant Institute.

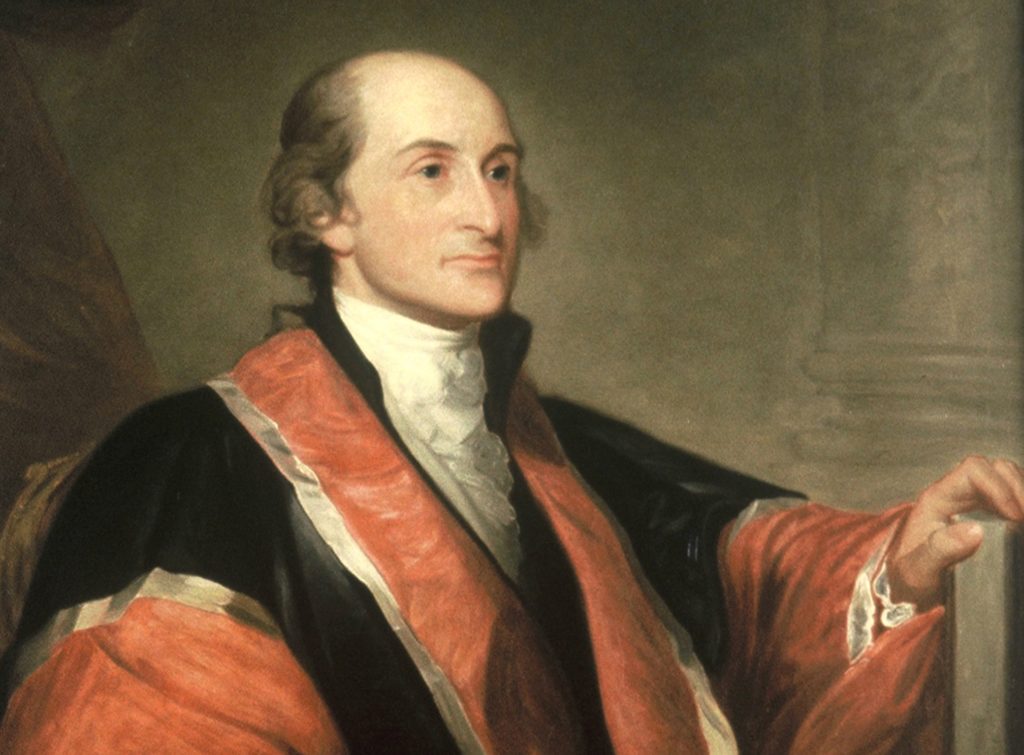

Image: Historical Society of the New York Courts

Brad Littlejohn, Ph.D., is a Fellow in EPPC’s Evangelicals in Civic Life Program, where his work focuses on helping public leaders understand the intellectual and historical foundations of our current breakdown of public trust, social cohesion, and sound governance. His research investigates shifting understandings of the nature of freedom and authority, and how a more full-orbed conception of freedom, rooted in the Christian tradition, can inform policy that respects both the dignity of the individual and the urgency of the common good. He also serves as President of the Davenant Institute.