Published November 21, 2019

Caitlin Flanagan has written a searing piece for The Atlantic titled “The Dishonesty of the Abortion Debate: Why We Need to Face the Best Arguments from the Other Side.” Flanagan argues that neither the pro nor the anti side of the abortion debate reckons with the best arguments of the other side. She then takes the reader through some heartbreaking true stories.

Flanagan is an affecting writer, and her plea that both sides of a bitter dispute offer more respect to the other is one with which I am in sympathy. But the argument she makes — movingly told as it is — is not quite convincing.

Flanagan reminds us of what women faced in the 1950s. A 1956 article in Obstetrics and Gynecology chronicled four cases of women who had been admitted to hospitals after undergoing “Lysol” abortions. One woman was rushed to the emergency room by her husband. On arrival, she had 104-degree fever and urine the color of “port wine,” indicating kidney failure. The husband confessed that two days prior, his wife had sought an abortion. The abortionist had injected the strong household cleaner Lysol into his wife’s womb. Flanagan writes:

Four hours after admission, the woman became agitated; she was put in restraints and sedated. Two hours after that, she began to breathe in the deep and ragged manner of the dying. An autopsy revealed massive necrosis of her kidneys and liver.

It was not an isolated case. The journal article recounted three other stories of women who had the same kind of abortion, and additional reports surfaced through other journals and court records. Women turned to Lysol because it was a common household product, would not arouse suspicion if a woman purchased it, and was marketed for years (in diluted form) as a contraceptive.

Flanagan also conveys the many ways in which women could feel trapped into seeking abortions in the Baby Boom era. Some women had terrible pregnancies, postpartum depression, or traumatic birth experiences. Some were married to abusive men who might blame their wives for an unintended pregnancy. Women’s desperation was understandable and tragic.

On the other hand, Flanagan writes, those ultrasound images leave us in no doubt — the fetus is a human baby. Flanagan’s response to the image of a twelve-week-old fetus is this:

Here is one of us; here is a baby. She has fingers and toes by now, eyelids and ears. She can hiccup — that tiny, chest-quaking motion that all parents know. Most fearfully, she is starting to get a distinct profile, her one and only face emerging.

“What I can’t face about abortion,” Flanagan writes, “is the reality of it: that these are human beings, the most vulnerable among us, and we have no care for them.” And so, she argues, the abortion extremists are “terrible representatives” of their sides.

Extremists are always offensive, but there are two glaring problems with this characterization. First, it is dated. In the 1950s, and in every decade in human history before that, contraception was inaccessible and often unreliable. For married women, this meant repeated pregnancies and births even when the couple did not want more children. In addition, strong stigmas attached to unwed childbearing. Women were thus forced into a vise — they could not prevent pregnancies, but their lives could be destroyed by shame if they carried a baby to term while unmarried. This didn’t justify abortion, and many women bore the shame rather than resort to it, but the bind it placed women in was harsh.

For good and ill, and I think it’s mostly for ill (but that’s a topic for another day), the stigma of unwed parenting is gone. Since the 1970s, contraception has become cheap and widely available. The Affordable Care Act mandates that contraceptives be covered with no out-of-pocket expenses for patients. At the same time, an estimated 2 million couples are currently waiting to adopt infants.

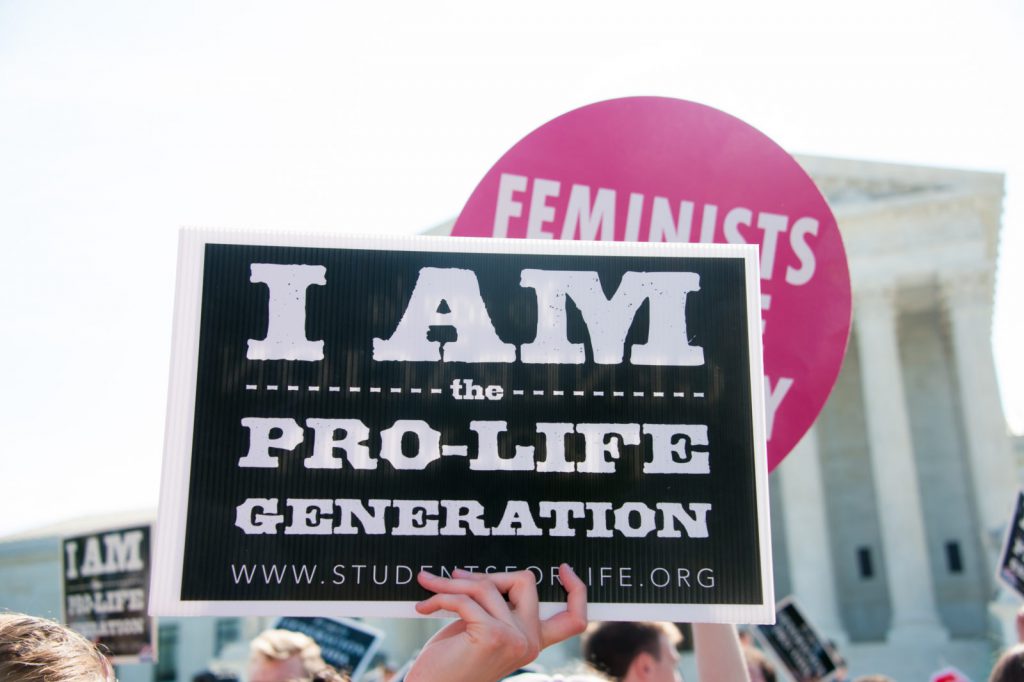

But the second problem with Flanagan’s analysis is this: What do pro-lifers argue that is dishonest? They are saying the very thing that Flanagan says she cannot deny — that the human fetus is a person, indeed, among the “most vulnerable” of people “and we have no care for them.” That is the essence of the pro-life case. They believe in the sanctity of life at every stage and therefore believe that, though crisis pregnancies are indeed severe challenges and can even be tragic, the “solution” of abortion is itself extreme.

© 2019 Creators.com

Mona Charen is a syndicated columnist and a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.