Published July 19, 2021

EDITORIAL NOTE: This essay is an excerpt from The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision. It is part of an ongoing collaboration with the University of Notre Dame Press. You can read our excerpts from this collaboration here. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

On the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson in March 1913, a grand parade marched on Washington, DC, featuring mounted brigades, ornate floats, musical bands, and thousands of predominantly women marchers in distinctive occupational garb. As the procession reached the U.S. Treasury building, the parade turned allegorical pageant, with costumed actors representing in turn Charity, Liberty, Justice, Peace, and Hope, “those ideals toward which both men and women have been struggling through the ages and toward which, in co-operation and equality, they will continue to strive,” according to the official program. The New York Times chronicled the pageant as “one of the most impressively beautiful spectacles ever staged in this country.”

Seven years later, after nearly sixty years of advocacy, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified, granting women in every state the right to vote. Nearly one hundred years after the Woman Suffrage Procession—just three years shy of the centennial celebration of the Nineteenth Amendment—another massive gathering in support of women’s rights was organized in Washington DC, this time the day after the inauguration of Donald Trump as president. If high ideals were present that day (represented, perhaps, by the slogan “Love Not Hate Makes America Great”), these were overwhelmed by the march’s official panel of speakers, who extolled “nasty” women, made generous use of expletives, and engaged in insult, threat, and ad hominem attack on the new president. The symbol of the march—the female genitalia—was depicted throughout the day in various manifestations on poster board and costume, but most memorably atop participants’ heads in the form of a pink “pussy hat.” Enduring moral principles, which women’s rights advocates in earlier days would have employed to make a reasoned critique of the controversial new president, had given way to vulgar irony: “This pussy grabs back.”

Something significant had changed over the intervening century in the cause of women’s rights. And it was not only that participants to the more recent Women’s March arrived by bus rather than on horseback, or that the women marching were as educated and professionally competent as the men, impressive though these changes are. Rather, the underlying rationale for women’s rights—for civil and political freedom and equality as such—has shifted profoundly. But this shift has occurred subtly and over time, such that many now falsely assume that an unbroken line can be traced from those who today agitate for women’s rights to those who argued that women had the right to do so in the first place.

Indeed, the philosophical and political principle of equal citizenship for women has morphed in the last half century into something that nearly contradicts its original moral vision, a vision first fully articulated by English philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman more than two centuries ago. For Wollstonecraft, political freedom and legal equality were not ends in themselves but necessary means to higher human ends: the common human pursuit of intellectual and moral excellence.

The political and civil rights Wollstonecraft claimed for women in the late eighteenth century have been over time and with great struggle steadily secured in modern democracies around the world. And yet the ennobling moral vision upon which she built her rights claims has largely been abandoned. With the stark moral failures of so many of our political, economic, and cultural leaders, the sexual exploitation of women and children through pornography and sex trafficking, the relentless violence that increasingly targets the most vulnerable human beings, the abject poverty of so many even amid ever-growing wealth, and the materialism and consumerism that works to corrupt the soul of the West, Wollstonecraft’s substantive vision may be needed now more than ever.

For Wollstonecraft, women’s capacity to reason, and thus to pursue reason to its proper ends, namely, virtue (imitation of divine perfection) and wisdom (imitation of divine reason), was the very foundation for women’s just claims to political freedom and equality. But not just for women: freedom as such a necessary means to these higher human ends. It was the forgetfulness of these noble ends, on the part of men especially, that facilitated the subjugation and victimization of women, even in their own homes.

A freedom bereft of wisdom and virtue reduces men to beasts, Wollstonecraft claimed. And this was especially true in intimate relations between men and women, the wellspring of the domestic affections she recognized as the source of every public virtue. Sexual integrity was not to be abandoned in the pursuit of equality between the sexes, nor was this virtue specially required of women, as was the convention of the day. Rather, it was men, who, in pursuing self-serving indulgence without habitual respect for women or regard for the noble purposes of sex and the goods of shared domestic life, had too often failed to treat women with the dignity they deserved. Women, for their part, had too often acquiesced, fashioning themselves more pleasing to the eyes than strong in the mind. Indeed, the eighteenth-century philosopher identifies want of chastity in men as the single most consequential offense against women. Wollstonecraft’s radical vision of sexual integrity for both sexes, with a view toward virtuous friendships of mutual trust and collaboration, poses an especially striking challenge to a modern-day women’s movement shaped, since the 1970s, by a very different kind of sexual revolution.

Wollstonecraft’s best-known work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was written in 1792, just two years after she published A Vindication of the Rights of Men, the first widely read critique of Edmund Burke’s famous 1790 defense of the British monarchy. Wollstonecraft wrote these treatises during a time of marked political and social change, as the American and then French revolutions threw off old forms of hereditary rule in their respective attempts (with greater and lesser success) to enact altogether new forms of republican government based on God-given rights, derived from the moral status of human beings as rational creatures.

In both books Wollstonecraft articulated this now familiar rationale for civil and political rights in the modern era, artfully extending its reach to women. But unlike most of her contemporaries, Wollstonecraft’s defense of rights was inspired by an ancient view of the human person, one that exalted the common human pursuit of wisdom and virtue above all else. She thus offered a unique synthesis of ancient wisdom and modern political insight, correcting errors she saw among philosophers of her day, and proposing a program that in its fullness remains still yet untried today.

Like her fellow travelers in the Enlightenment period, Wollstonecraft extolled freedom from illegitimate and arbitrary power, but not a freedom left to its own devices. Civil and political rights for both men and women were essential to human dignity and political progress. But such rights were themselves born of moral duties to self, family, fellow citizens, and God. That is, political freedom was at the service of the moral development of each person, which consisted, in large measure, of virtuously fulfilling the ordinary duties of life.

Wollstonecraft did not preach sanctity in a religious sense, but a religious perspective did inform her thinking. She sought instead to enunciate the moral duties that characterized rational creatures, duties to self (to develop one’s rational faculties and master one’s appetites), to family (to care for one’s dependent children, spouse, and elderly parents), to fellow creatures (to be useful in one’s work and respect the human dignity of all others, regardless of social status), and to God (to pursue truth and goodness and to trust in his providential designs). As the content of her children’s stories attest, Wollstonecraft viewed the affectionate inculcation of virtue in children to be among the most essential of all social duties, and so motherhood and fatherhood the very highest of callings.

Wollstonecraft’s appeal for women’s education is her most remembered contribution today; her rationale perhaps less so. The self-taught philosopher believed that if women, like men, were afforded both intellectual and moral formation and the opportunities to engage in more serious-minded occupations, they would enjoy greater independence of mind and in turn better appreciate their distinctive duties to their families and beyond. Wollstonecraft’s view of marriage in her Rights of Woman—a relationship of reciprocity and friendship between equals, a shared project for the upbringing of children, and the best means to restore harmony between the sexes—remains the treatise’s most farsighted vision. Given the dangerous political upheaval that served as the context of her first romance, the unjust marital laws that existed in her time, the cruel abandonment she experienced at the hands of her first child’s father, and her untimely death just after the birth of her second child, she was not able to live out that vision for long. But it still has much to teach us today.

Wollstonecraft became a scandal in her day, less for her revolutionary ideas than for the incomplete picture of her tragic personal life imprudently published by her bereaved husband, William Godwin, in the months following her death. But although many of the themes Wollstonecraft first articulated in Rights of Woman emerged energetically in the political and legal writings of generations of women’s rights advocates, in her own country, and particularly in the young United States, she proposed a far more substantive moral vision than what is often represented today as a treatise in favor of women’s rights in marriage, education, employment, and political participation. Now, more than two hundred years later, we may yet be ready to hear all she had to say.

Emboldened by her insights on work, marriage, children, virtue, and rights, a renewed women’s movement might make itself a catalyst for the regeneration of marriages and families, the revaluing of caregiving and the reshaping of work, and the reconstituting of a morally embattled nation. Sometime in the last half century, the women’s movement lost its way. It’s high time to reclaim that lost vision.

+

The trouble with modern feminism today lies not with its most basic critique, as embodied in the myriad antidiscrimination measures brought about in the 1960s and 1970s. Wollstonecraft had claimed, like advocates of women’s equality in the Middle Ages and Renaissance before her, that women’s true intellectual capacity would remain unknown until women had equal access to education and more serious-minded occupations. Thanks to decades of educational and workplace reforms, false assumptions of woman’s inferior nature finally have been put to rest. The trouble with modern feminism lies, rather, in its near abandonment of Wollstonecraft’s original moral vision, one that championed women’s rights so that women, with men, could virtuously fulfill their familial and social duties. Nowhere is such an abandonment clearer than in the revolutionary assault on the mutual responsibilities that inhere in sex, childbearing, and marriage that began in the 1960s and 70s.

Disentangling the original vision of the rights of women from the excesses of the sexual revolution may sound near impossible, but if rehabilitated, it is a vision both women and men could embrace today. Indeed, it is one that is already taking shape among some of the most well-off and educated in our society, as they increasingly embrace a vision of marriage as a friendship of equals, and shape their progressively flexible work lives around the caregiving needs of their families. And, in the most rudimentary of ways, it is a vision that is being articulated by some powerful women, even if they would themselves spurn what I regard to be some of its most necessary elements.

Princeton professor Anne-Marie Slaughter, one of Secretary Clinton’s top aides at the State Department, became, with her widely read Atlantic article, “Why Women Still Can’t Have It All,” an outspoken proponent of a revaluation of caregiving and a prioritizing of the family within the women’s movement. In her popular book Unfinished Business, Slaughter argues that the women’s movement has mistakenly “left caregiving behind, valuing it less and less as a meaningful and important endeavor.” Now, Slaughter is not calling for a return to the 1950s. Few of us are. But Slaughter writes glowingly of her own happy marriage, and forthrightly acknowledges that women today still tend to place the care of their families ahead of their own professional advancement. She seeks instead to invite men into the caregiving enterprise, suggesting that if our society better valued caregiving, then perhaps men would do more of it, and we would see greater equity in both the home and the workplace.

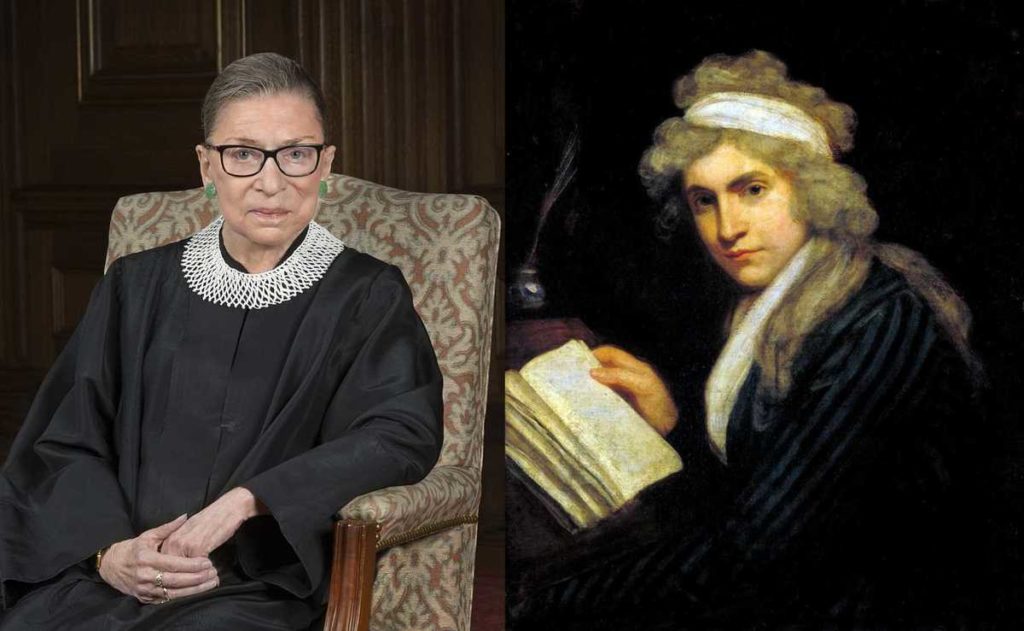

Slaughter follows a long line of scholars and advocates who have been working toward just this substantive goal, with the celebrated women’s rights advocate and Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the very forefront. The late Justice Ginsburg undoubtedly wished for more couples to enjoy the happy situation that she and her beloved husband of fifty-six years enjoyed: a marriage of equals in which each spouse dedicates oneself to work and family with deep respect for the joys and duties of both avenues of fulfillment. Indeed, Ginsburg herself would seem to be the leading icon of Wollstonecraft’s vision for women.

But as inspiring as women like Ginsburg and Slaughter are to many up-and-coming young professionals, theirs are stories of great privilege, and not just in terms of the resources and flexibility that come with high-status work. Their stories share a profound appreciation for and dedication to marriage at their very core. Indeed, it is hard to read the stories of these successful women, both mothers, without underscoring the relentless support and fidelity of their husbands. And not just women at the pinnacle of their professions. Marriage and child-rearing go hand in hand among the wealthier across the board, and women of all professions, including “at-home mothers,” are the better for it. These women’s success stories, then, are not first about sexual freedom and equality as individual autonomy. They are the stories of the excesses of the sexual revolution spurned.

Ordinary women have not been so lucky. Solid marital ties that, for most of our country’s history, bound men and women together with their dependent children—collaborative, loyal bonds of kinship and care that enabled working-class and immigrant families to rise into the middle class and enjoy the “American dream”—are no longer holding sway. Growing income inequality, economic insecurity, and threats to social cohesion have many causes, but the diametric trajectories of the marrying rich and unmarrying poor bear a good share of the blame. Economists and other social scientists have offered various explanations over the last several decades for the sharp decline in marriage, the rise in nonmarital childbearing among disadvantaged women, and the feminization of poverty that has accompanied both. But what has become increasingly difficult to ignore is the way in which the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s dramatically altered the circumstances in which poor women bear and raise their children. The decoupling of sex from marriage and marriage from childbearing, ushered in by the sexual revolution, unraveled a working-class culture of once stable marital bonds that children need and both mothers and fathers once relied upon for their success at home, at work, and in all of life.

Women in the United States and other Western nations now enjoy untold educational and employment opportunities, won through landmark advances in antidiscrimination law and other state protections and cultural gains. But unmarried women who raise children without the emotional and financial supports of their children’s fathers are at a stark disadvantage on any number of measures when compared to those women who raise their children within the marital bond. Again, the most well-educated women in the United States have not abandoned marriage in favor of total independence from men, as more radical feminists, insistent on the inherent patriarchal nature of marriage, suggested in the 1970s that they do. No, college-educated American women (“the most economically independent women in the history of the nation,” according to a noted scholar at the Brookings Institution) are getting and staying married at the highest rates of all demographic groups today. Whether working outside of the home or exclusively within it, these elite women well understand the unique contributions their husbands make to their children’s well-being and to their own happiness. They also understand the central Wollstonecraftian principle that collaboration and reciprocity in their marriages is the surest ticket to their children’s well-being—and to their own.

Slaughter’s efforts to elevate the culturally essential work of caregiving, built upon the scholarship and advocacy of decades of “relational feminists” before her, are an advance for modern feminism, and so too an advance for women and for families. But a deep contradiction still riddles modern feminism from within, and without an understanding of the nature of the contradiction, even this newfound appreciation for duties of care—including Slaughter’s own invitation to men to take part in more caregiving—modern feminism will not be set aright. The cause of women’s rights will only become what Wollstonecraft envisioned, a cause that honors both caregiving within the home and professional work without, when it firmly reestablishes the responsibilities that accompany sex.

Well before Slaughter called for a new men’s movement to better value the work of caregiving, generations of men were already doing so, albeit in more traditional settings than many are today. Devoted husbands and fathers both traditionally and often today sacrifice time with their families to earn a living for their families, so that the essential duties of nurture and caregiving, so often managed primarily (and often quite happily) by women, would be protected and preserved. These men understand what Wollstonecraft hoped they would, namely, that marital and paternal responsibilities accompany marriage and childbearing, and the sexual act has an intimate connection to both. Indeed, it is precisely this connection, between sexual activity and potential fatherhood, that Wollstonecraft strongly defended, and that the sexual revolution devastatingly eclipsed. And it has left the most vulnerable of women (and their children too) more vulnerable today than nearly anytime in modern U.S. history.

Once understood as the necessary means toward the higher human goods of virtue and wisdom, goods first learned through the interdependent bonds of familial solidarity and affection, we are now told that freedom and equality ought to include that act that tears at the first bond of human affection, between a mother and her unborn child. But easy abortion access has not rendered women freer or more equal, as much as the U.S. Supreme Court in Planned Parenthood v. Casey suggested it might have. Instead, it has distorted the shared responsibilities that adhere in male-female sexual relationships, promoted a view of childbearing as one consumer choice among many, and has greatly contributed to the dim view of caregiving ever since.

More still, the relentless quest for abortion rights over the last several decades has placed the modern-day women’s movement squarely on the side of the individualistic and consumerist economy, ever hostile to the priorities of the child-rearing family, and so diametrically at odds with the market-resistant logic for which the women’s movement originally stood.

Before the late 1960s, those advocating abortion mainly had done so for eugenic and population-control reasons, with women’s rights advocates standing historically opposed to the practice in promoting an ethic of solidarity, care, and the shared duties of both mothers and fathers. Nineteenth-century women’s rights advocates, who had won for women the right to vote, regarded abortion as an act of violence against an innocent unborn child, a reality advances in modern science have only made clearer. They, like Wollstonecraft before them, also intuited what social scientists have described in our time: that sex unmoored from its reproductive potential would increase sexual risk-taking, particularly among men, and that the negative effects of what economists now call “low-cost” sex would redound disproportionately to women, especially among the most vulnerable.

Like today’s feminists, both Wollstonecraft and early women’s rights advocates were deeply critical of the sexual double standard that shamed women for behaviors that men freely indulged in. But these early generations of women’s advocates worked not for women to imitate dissolute men, as organizers of the 2017 Women’s March seemed keen to do. Instead, Wollstonecraft and the suffragists argued for sexual integrity for both sexes. “Votes for women, chastity for men” was actually a suffragist slogan. Indeed, out of respect for both the reproductive potential of sex and women’s distinctive reproductive capacity, many nineteenth-century women’s rights advocates and their husbands practiced periodic abstinence, what they called “voluntary motherhood,” an early precursor, not to abortion (or even contraception, which most of them opposed for the selfsame reasons), but to natural methods of fertility regulation, which have only grown more scientific and effective in our day. Sexual integrity, on this account, was a necessary precondition to authentic equality, and harmonious companionship, between women and men. It is worth asking whether this belief could still be true today.

Erika Bachiochi is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a senior fellow at the Abigail Adams Institute, where she founded and directs the Wollstonecraft Project. She is the author of The Rights of Women: Reclaiming a Lost Vision.

Featured Image: Combination of [right] John Opie’s Portrait of Mary Wollstonecraft and [left] Official Portrait of Ruth Bader Ginsburg; Source: Wikimedia Commons, PD.