Published June 16, 2022

This article is adapted from Ryan T. Anderson’s contribution to Matthew Nelson’s new collection of essays, The New Apologetics: Defending the Faith in a Post-Christian Era(Word on Fire, 2022).

“It’s not a baby, it’s just a clump of cells.” “OK, sure, what I mean is even if it’s a human being, it’s not a person.”

“That’s not my wife anymore, that’s a vegetable.” “OK, sure, that’s her body, but she left the body a long time ago when she started losing her mind.”

“Love is love, the plumbing doesn’t matter.” “OK, sure, we can’t literally unite as one-flesh, but that’s just poetry anyway, all that matters is that we express our love—how we do it isn’t important.”

“I’m a woman trapped in a man’s body, the doctors got my ‘sex assigned at birth’ wrong.” “OK, sure, maybe sex isn’t technically ‘assigned,’ but the real me is a woman and modern medicine can affirm my ‘gender identity’ through hormone therapy and surgery.”

Body-Self Dualism

Perhaps you’ve heard various versions of these arguments in recent years. We could undoubtedly multiply them, both on these four issues, and on countless others. To be intelligible—let alone plausible—they assume a single anthropological fallacy: body-self dualism. Whether you’re discussing abortion or euthanasia, same-sex marriage or transgender ideology, it is highly likely that body-self dualism will be either explicitly appealed to, or implicitly assumed, as the conversation plays out.

Any number of honest pro-choicers have to recognize the now-irrefutable biological reality that the life of a human being begins (at the very latest) at the completion of fertilization, when the two gametes (sperm and egg) that gave rise to the newly formed embryo cease to exist, their pronuclei line up, and a new organism begins its integral, self-directed growth from the embryonic stage of human existence to the fetus, newborn, toddler, child, teenager, and reader of this book. Each of these terms—embryo, fetus, newborn, toddler, child, teen, reader—describes one and the same organism, just at different ages or stages of development. Honest pro-choicers can’t deny this.

Likewise, most pro-choicers are reluctant to give up on human dignity and equality. They want to affirm that it’s wrong to devalue—let alone kill—individuals of any class of humanity. But if a human being begins at conception and all human beings have equal dignity, how could you justify abortion? Simple—you explain that human dignity and equality are for “persons” and the unborn human being is not yet a person. To be a person—to be a “self,” to matter morally—is to have self-awareness, self-consciousness, and higher mental life. All entities with that have dignity, or so the argument goes. I’m a self, but I was never really a fetus—that was just the physical preparation of me.

And so, too, there might be living physical remains of “me” before my body dies and leaves behind a corpse. That is, even as my heart continues pumping and my lungs continue breathing, the real me, the conscious “self,” might depart my body. What’s left might be called a “vegetable”—in a revealing attempt at dehumanization. No one denies that the patient in a so-called “persistent vegetative state” is a living human being, they just deny that it’s a human person, a self. The same is true for children—like Alfie Evans and Charlie Gard—whom the powerful view as having lives unworthy of living. Yes, they’re living human beings, but they’re not human persons in the way that matters. Why not? Because they aren’t capable—here and now—of personal actions, of self-awareness and consciousness and the acts that manifest such “higher” mental life.

What’s true of these debates at the beginning and end of life is also true of our debates about human sexuality: dualism plays a foundational role. This was evident during the debate over the very nature and definition of marriage, but it undergirds the entire sexual revolution. If our bodies are just instruments of our conscious, desiring “self,” then bodily union just as such is insignificant. What matters is “personal” union—understood as an emotional or romantic thing—where the body is a mere instrument at the service of the personal self. The “plumbing” doesn’t matter, so long as the body is being used in a way that both (all?) parties to the encounter find expressive of their emotions, or at least pleasurable. Whether it be same-sex or opposite sex, monogamous or polyamorous, permanent or temporary, exclusive or open—it’s neither here nor there, so long as the sexual bodily action is at the service of the desiring conscious self.

Rather than conform thoughts, feelings, and actions to objective reality, modern man’s inner life itself becomes the source of truth.

And once we’ve said that about our sexual actions, why not say the same about our sexual identity? Though here we use the word “gender” to further separate bodily sex from an inner sense of “gender identity.” But the same basic framework is at play: The real me is something other than my physical body, there’s a real me to either be discovered or created (the various gender ideologues conflict on this point), and then my body should be transformed to align with the “gender identity” of the inner (real) me. Some go so far as to claim that sex is “assigned at birth”—with the implication being that sex can later be “reassigned.” More cutting-edge gender theorists, though, use the language of “gender confirmation” and now “gender affirmation” to describe the various medical procedures performed on the (mere) body to “affirm” that inner self.

Expressive Individualism

The attentive reader will have noticed that body-self dualism is intimately related to expressive individualism, another key anthropological fallacy of our age. If the body is a mere costume or vehicle—an instrument of the desiring self—then that self should use the body to express its inner truth. Of course the person of the Psalms, of St. Paul’s epistles, and of St. Augustine’s Confessions was also a “self” in the sense of having an interior life. But the inward turn of the biblical tradition was at the service of the outward turn toward God. The person was a creature of God, who sought to conform himself to the truth, to objective moral standards, particularly having to do with his bodily self, in pursuit of eternal life.

Modern man, however, seeks to be “true to himself.” Rather than conform thoughts, feelings, and actions to objective reality (including the body), man’s inner life itself becomes the source of truth. The modern self finds himself in the midst of what Robert Bellah has described as a culture of “expressive individualism”—where each of us seeks to give expression to our individual inner lives, rather than seeing ourselves as embodied beings, embedded in communities and bound by natural and supernatural laws. Authenticity to inner feelings, rather than adherence to transcendent truths, becomes the norm.

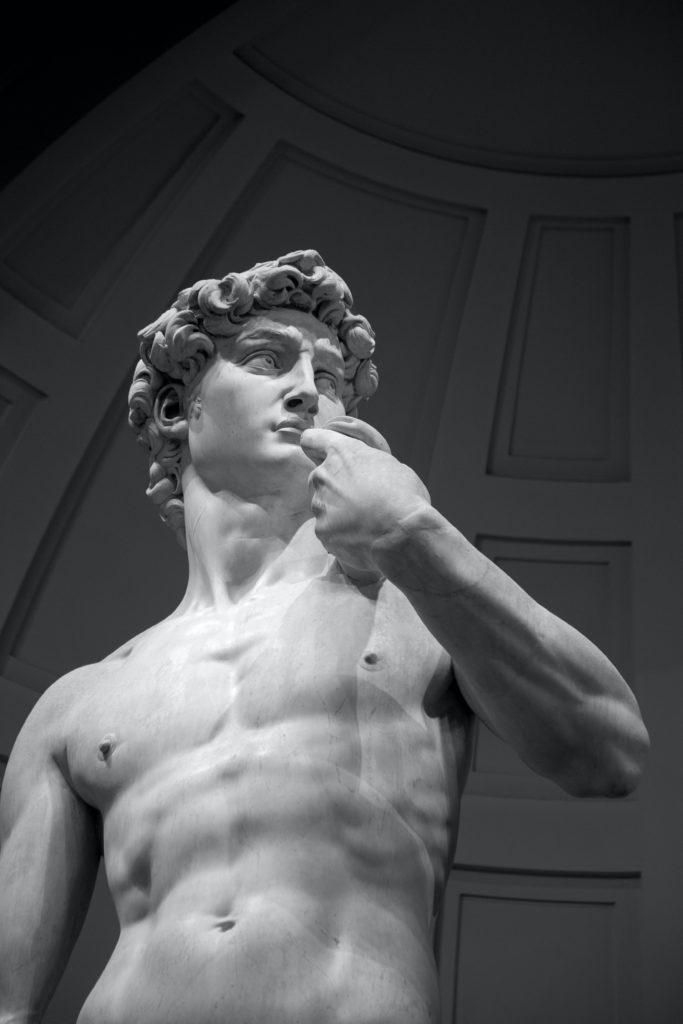

Rather than seeing ourselves as what Gilbert Ryle referred to as ghosts in machines, where the real self is the mind, or the will, or the consciousness, that somehow inhabits a body and makes use of the body as a mere instrument, we should see ourselves as incarnate, bodily beings—dependent rational animals, as Alasdair MacIntyre explains. Only if my body is me, if I’m an embodied soul, or an ensouled body, a dynamic unity of mind and matter, body and soul, can we make sense of the truthful positions on these four issues. Given our bodily nature—which itself is a personal nature—certain ends are naturally good for us. Body-self dualism, and its social manifestation in expressive individualism, underlie the rejection of our given human natures with given human goods that perfect our natures.

So any effective apologetics agenda on anthropology would need to center on responding to body-self dualism and the rejection of natural law that expressive individualism entails. This will require work from philosophers and theologians to communicate the theoretical problems with dualism, along with scientists and social scientists (including medical doctors), to show the practical realities of our life as embodied beings. But most importantly it’ll take the work of artists to dramatize the truth of our embodiment, and of the Church to ritualize it through sacraments and liturgy.

Photo by Jianxiang Wu on Unsplash

Ryan T. Anderson, Ph.D., is the President of the Ethics and Public Policy Center.