Published August 18, 2018

In 2018 we have come, finally, to the punch line of an old joke—the one that ends with Tonto asking the Lone Ranger: “What do you mean ‘we,’ paleface?”

The joke originates in radio. In the mythical early days of the Western United States, the announcer told us, a masked man and an Indian rode the plains, searching for truth and justice: “Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. From out of the past come the thundering hoofbeats of the great horse Silver.” In a jitter of neurons, however, the mind grasps that jesting Tonto has a different myth in mind—the Little Bighorn.

White men on watersmooth silver stallions ride forth with Gen. Custer, all white hat and flowing yellow hair. The regimental band, ridiculously clad in long white dusters, plays “Garryowen.” Then the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho and other people of color on horseback materialize and cause white people in the immediate vicinity to disappear. Tonto takes white men’s scalps.

The joke seems less funny today. Now Tonto does the laughing. The moral ground of his question has shifted. Betrayal is the way to his own truth: No more Kemosabe. There’s a shock of awareness all around.

Have we reached the tilting point on the subject of race? Americans don’t quite know anymore what they mean when they say “we.” In the color hierarchies—the caste systems—of the old America, everyone knew well enough. They knew who was in and who was out. They knew the boundaries and categories. Now a country in the process of expanding its first-person plural becomes more inclusive and, at the same time, more balkanized.

U.S. society has been fragmented by identity politics into warlord states and has become, here and there, almost psychotic. Civilized people get themselves worked up at dinner parties. They use the phrase “civil war,” and on the third glass of wine, they mean it. People unsure of who they are have no idea what they, or the other side, may be capable of. A strange interplay of candor and evasion goes to work, but all forces are centrifugal. When Ta-Nehisi Coates says “we,” he doesn’t mean me. I am the blue-eyed white devil slave master. Not in my own eyes but in his.

The public narrative is filled with alternate fantasies of annihilation. Either Robert Mueller is about to crush Donald Trump and cast him and his kind into outer darkness, or Mr. Trump will obliterate Mr. Mueller and, with him, the left and its useful-idiot media. Conjectural nuclear or environmental apocalypse flickers just over the horizon.

Nothing is more personal than race, which is the underlying master theme. On that subject, Americans have been at each other’s throats from the beginning. The public is personal: I think of my great-grandfather, Albert Payson Morrow, who would have died that day with Custer if, after the Civil War, he had stayed in the Seventh Cavalry. If he’d gone west with Custer and the Seventh, and had died at the Little Bighorn, there’d have been an annulment of subsequent Morrows along the Albert line. I would not be here to write this. Strange, in 2018, to find oneself dodging an arrow that left a Cheyenne warrior’s bow in 1876.

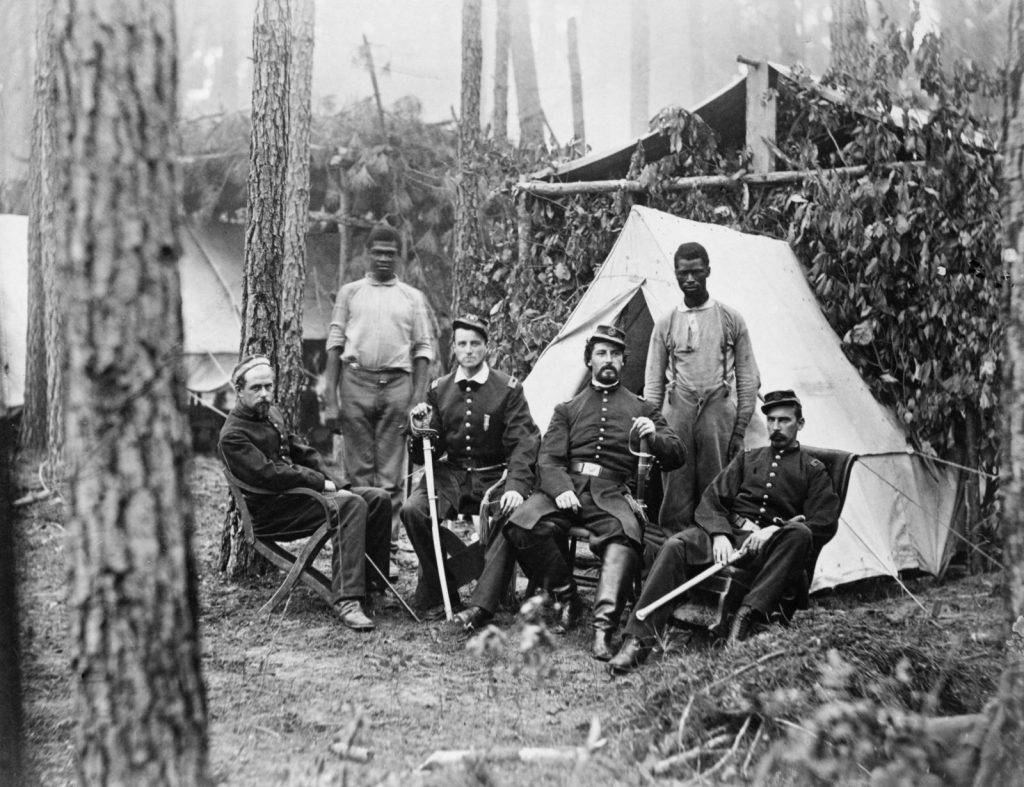

Albert was a hard-riding, handsome young man. “The very devil with the ladies,” a fellow officer said. Only in his mid-20s at the time of Appomattox, my great-grandfather had been brevetted lieutenant colonel because of his reckless bravery at Gettysburg, Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg and every other major battle of the eastern theater of the war. He was wounded five times, captured three times (twice by J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry and once by Mosby’s Rangers), and exchanged three times in the long crusade. It was at Dinwiddie Station, a few days before the end of the war, that he received his last bullet, a severe wound to hip and leg that caused him misery for the rest of his life. After the war he signed on as a major with the newly formed Ninth Cavalry, a regiment recruited among former slaves from the plantations of Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. Expert with horses, they were able, daring men who would be called “the Buffalo Soldiers.”

Morrow went west with his black centaurs to Texas and New Mexico. Eventually, he would command the regiment. Here were white officers leading black troops as they fought red Indians, either killing them or hounding them onto reservations or back across the Rio Grande in what was, in essence, police work. The funny thing is that on all three sides—white, black and red—there was the warrior’s mutual respect. The tale would become a Caucasian’s Iliad in the hands of John Ford and John Wayne. White people (to borrow Saul Bellow’s phrase) had movies to keep the wolf of insignificance from the door.

No one’s a hero all the time. Albert Morrow seems to have grown bitter on the dismal frontier posts, frustrated at being passed over for general. He was court-martialed once for being drunk on duty and another time for a taradiddle with his pay stubs. President Grover Cleveland, considering his hard service and his wounds, pardoned him. On the other hand, I admired the style of his wife, my great-grandmother Ella Mollen Morrow. One night at the fort, when the colonel was away scouring the plains for Native Americans, she shot a would-be rapist dead with a Colt .44. The Army didn’t even bother to investigate the incident.

When Albert retired a full colonel, he and Ella moved to Florida. He died of complications from the bullet lodged in his leg. It went with him to the grave.

I’d hoped that Col. Albert had paid the family’s racial dues. He risked his young life for four years against Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. But my brother Hugh discovered not long ago that some of our relatives in southeast Pennsylvania had joined the Ku Klux Klan during its revival in the 1920s. We found them posing stiffly in a cracked black-and-white photograph—lean, humorless Protestants in bedsheets and cone hats, staring straight into the photographer’s lens. Their complaint, I gather, was less against blacks than immigrants. It was comforting to learn that after a year or so, they became disillusioned with the Klan and quit, and had the grace to be ashamed of themselves. Americans may sometimes be redeemed by their second thoughts.

Shall we have civil war or second thoughts? This story started a long time ago. It will go on. I hope that we—left, right and otherwise intoxicated—still have the capacity for shame and self-knowledge. Poor, dumb George Custer undoubtedly had second thoughts, but it was too late.

Mr. Morrow, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, is a former essayist for Time.