Published March 6, 2018

Rating: 1 out of 2 stars (read about the rating system here)

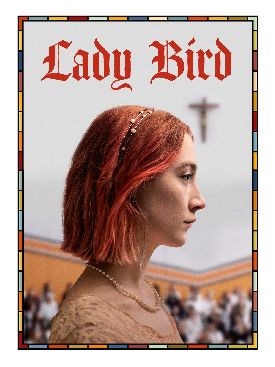

Set in Sacramento in 2002-2003, Greta Gerwig’s female coming-of-age story Lady Bird provides two main points of perspective on the otherwise claustrophobic representation of that city — “the Midwest of California” — which its eponymous heroine (Saoirse Ronan) is so eager to escape, along with her Catholic high school and the mother (Laurie Metcalf) with whom she constantly quarrels. One of these is post-9/11 New York, which is where she wants to escape to, for “cultural” reasons — Connecticut and New Hampshire would be her second and third choices, she says. The other non-Sacramentan perspective is supplied courtesy of the Iraq war, which is only referred to directly once or twice, but TV reports of which periodically anchor the film as firmly in time and political space as Sacramento does in place.

Lady Bird — a given name, she says, in the sense that she gave it to herself in preference to the one her parents gave her, which was Christine — is a charming high school senior with “a performative streak” who doesn’t say much about the war except when a boyfriend named Kyle (Timothée Chalamet) tries to talk her out of her disappointment with her first experience of sexual intercourse. After telling her, “You’re going to have so much unspecial sex in your life,” he reminds her of civilian casualties in Iraq. “Different things can be sad!” she snaps at him. “It’s not all war!” Then she asks anxiously: “Are we still going to the prom together?” The personal and the political are always kind of mixed up for Lady Bird.

When she first meets Kyle, he is reading the late Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States, which seems to have formed his own view of the world outside Sacramento. Lady Bird is soon reading the book herself and appears to be be working her way up to a Zinn-like hatred of America by her hatred of Sacramento. But she takes left-wing politics for granted even before she meets Kyle. When her friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein) asks if she isn’t afraid of terrorism in New York, she replies: “Don’t be a Republican.” And when she sees a “Reagan Country” poster in the house belonging to the grandmother of another boyfriend (Lucas Hedges) she asks if it is a joke. It is not.

An important datum in understanding her attitude, both while she is living in Sacramento and after she has left it, is her family’s socioeconomic position there. Both boyfriends belong to Sacramento’s upper crust while Lady Bird comes from what she calls the wrong side of the tracks. Her family is intact, but the employment of her father (Tracy Letts) is precarious and her mother has to work double shifts as a psychiatric nurse in order to keep their heads above water. An older brother (Jordan Rodrigues), apparently by a different father, and the brother’s girlfriend (Marielle Scott) live with them and have menial jobs. On the rare occasions when Lady Bird and her mother are getting along, they like to spend their Sundays touring open houses in the rich part of town.

The main point of contention between Lady Bird and her mother is the latter’s firm belief that the former’s desire to go East to college is foolishly improvident and far beyond the family’s means. There may also be just the hint of jealousy that the rest of the family has had to be content with Sacramento State, so what makes Lady Bird — mom tries to remember to call her by her made-up name — think she’s so much better than they are? Lady Bird has to go behind mom’s back to get her more indulgent father to fill out the financial aid forms for her, and this causes yet another explosion when mom finds out about it. The intensity of the family dynamics is set against a social and political background that seems to be taking us one way but ends up taking us in quite a different direction, and the movie is all the better for that.

Its pivotal point comes as Lady Bird talks to her favorite teacher, Sister Sarah Joan (Lois Smith), about her college essay which, as the Sister reads it, tells her that, “You clearly love Sacramento.”

An incredulous Lady Bird replies: “I do?”

“You write about Sacramento so affectionately and with such care.”

“I was just describing it.”

“Well it comes across as love.”

“Sure, I guess I pay attention.”

“Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing? Love and attention?”

Not right away but eventually Lady Bird is also able to see the love in the previously unwelcome attentions of her mother and of the good sisters of Immaculate Heart High. And when she does, the moment is symbolized for us by her choosing to be known by her real name. “People go by the names their parents give them, but they don’t believe in God,” she says to another would-be boyfriend named Dave (who professes himself an atheist) — before introducing herself as “Christine.”

Among several great and funny lines in the movie, one of the best is when mom says to Christine: “I want you to be the very best version of yourself that you can be,” and the latter replies: “What if this is the best version?” It expresses an eternal teenage anxiety but one which, fortunately, nearly all kids eventually grow out of. Ms Gerwig, who both wrote and directed the film, has done a wonderful job of taking us through that process step by step in a way that feels entirely right.

James Bowman is resident scholar at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.