Published October 7, 2018

Note: This piece was originally published under the headline “To Bring Back U.S. Manufacturing, Get the World to Dump the Dollar”

Donald Trump promised to “make America great again,” but he might make America Great Britain. To re-industrialize the U.S. economy, President Trump must avoid the mistake that de-industrialized Britain: namely, he must end the dollar’s role as the world’s chief reserve currency.

A century ago when Britain began to lose its place as the world’s leading power, it was suffering economic maladies today’s Americans will find familiar: declining exports, large government deficits, and a huge amount of foreign debt. The British pound’s role as the world’s chief reserve currency was a major driver of this economic decline.

John Maynard Keynes promoted the British pound’s use as the world’s reserve currency, writing in 1913 that replacing gold with foreign-exchange reserves was a step toward “the ideal currency of the future.” But it didn’t take long for the markets to prove that currency reserves are not a foolproof form of savings. The monetary system Keynes recommended was established throughout Europe after a 1922 conference in Genoa, but it collapsed in 1931 at the onset of the Depression.

French economist Jacques Rueff described the fatal weakness of foreign-exchange reserves in a 1932 lecture. He explained that when a monetary authority accepts dollar or sterling claims for its official reserves rather than gold, purchasing power “has simply been duplicated,” so that, for example, “the American market is in a position to buy in Europe, and in the United States, at the same time.” In other words, when a foreign nation accepts repayment in U.S. dollars it increases its money supply without diminishing the U.S. money supply, allowing both countries’ central banks to lend in dollars.

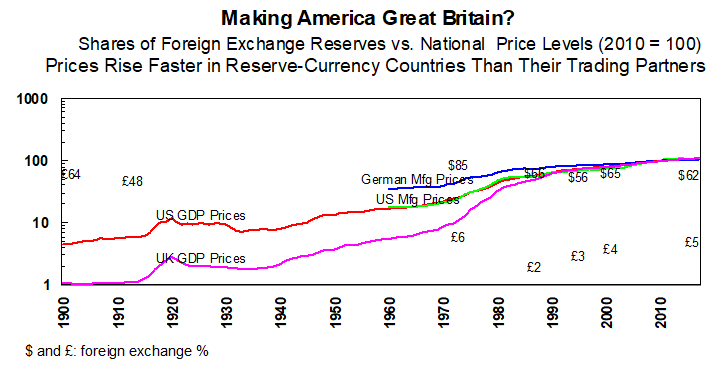

This credit “duplication” is not only inflationary in the reserve-currency country and any country whose currency is tied to the reserve currency; it also necessarily causes the average price of goods to rise faster in the reserve-currency country than among its trading partners. This is why Britain’s and America’s manufacturing industries lost their competitiveness as exporters, resulting in deindustrialization.

This so-called Triffin Dilemma, though first described by Rueff, was named around 1960 for the Belgian-American economist Robert Triffin, who described the post-World War II unraveling of the Bretton Woods gold-exchange system. Under the gold standard, the world-wide increase in monetary gold equaled the world’s net exports. The problem of the Triffin Dilemma is that every additional dollar of foreign-exchange “reserves” must be matched by an equal deficit in the reserve-currency country’s net exports—that is, by net imports.

The glut of reserve currencies made the 20th century a period of intense inflation. The average price of British goods increased 72-fold from 1900 to 2000, while U.S. prices rose 18-fold over the same period. These increases far outpaced inflation in other major export countries that did not provide international reserve currencies. The prices of German, Japanese and Chinese goods all have fallen compared with U.S. exports.

Tariffs and other forms of protectionism can’t restore America’s export competitiveness. They invite retaliation, inhibit trade, and raise prices even higher. The uncompetitive U.S. price level is effectively a tariff on American goods. Thinking that another tariff will help American workers makes no more sense than believing one can heal the injuries of a pedestrian hit by a car by backing up over the victim.

The Triffin Dilemma can’t be solved without a monetary reform that ends the dollar’s use as the world’s chief reserve currency. Here’s a deal that could place Mr. Trump in Alexander Hamilton’s league: Persuade America’s sovereign creditors that the U.S. will convert every penny of foreign dollar reserves into long-term government-to-government debt, to be paid off in gold over, say, 30, 40 or 50 years. Hamilton’s plan paid off the debt from the American Revolution by the mid-1830s. The gradual repayment of all outstanding official foreign dollar reserves would reverse America’s industrial decline by restoring the price competitiveness of U.S. manufacturing.

The most essential step would be establishing a schedule for paying off the outstanding dollar reserves, which would require long-term planning and consensus between the White House and Congress. But if a payment schedule were finally set, it would remove the deflationary threat of foreign dollar reserve liquidation overhanging the U.S. market. Then the beginning of the actual payments would set in motion the relative price changes necessary to reverse the reserve-currency curse.

Like Mr. Trump, Hamilton’s contemporaries originally thought his glaring character flaws far outweighed his virtues. But after the formerly penniless immigrant managed to make a fortune for his adopted country, even those who had been his worst political enemies found it in their interest to carry out his plan for decades. Today, young people whistle the songs not from “Jefferson” but “Hamilton.” There will be no whistling of tunes from “Trump” if he makes America Great Britain.

Mr. Mueller directs the economics and ethics program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.