Published November 2, 2020

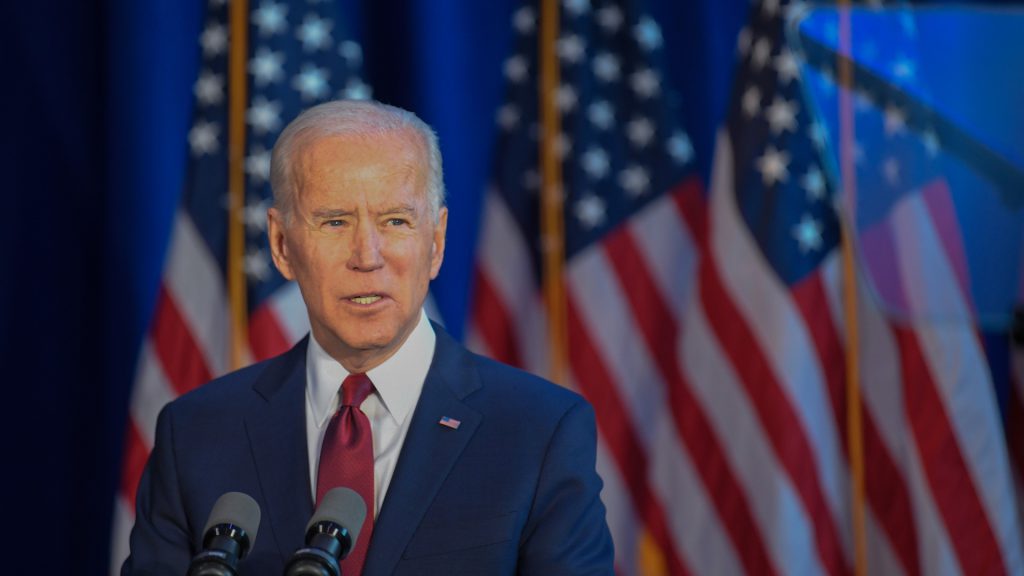

In the entire history of American presidential campaigns, there may never have been a wider gap in empathy than between Donald Trump and Joe Biden. And it has rarely mattered more.

Empathy is the quality of putting yourself in the place of another, understanding how they are experiencing the world, identifying with their feelings, and being able to communicate that understanding to them.

“Rarely can a response make something better,” according to Brené Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston Graduate College of Social Work. “What makes something better is connection.” And empathy is all about connection, about allowing others to feel heard and accepted.

But things hardly stop there. Trump has shown time and again that he delights in hurting those he deems to be threatening or insufficiently loyal to him. We saw that in the way he relentlessly humiliated former Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the first senator to endorse him in the 2016 GOP primary. Trump has publicly mocked Sessions as “weak,” “disgraceful,” and “scared stiff”—and according to reports, he’s called Sessions “mentally retarded,” an “idiot,” a “dumb Southerner,” and “Mr. Magoo.” Why? Because Sessions rightly recused himself from a Department of Justice investigation into the 2016 campaign, which eventually led to the appointment of Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

Trump has used the unmatched influence of his office to advance a twisted understanding of manliness, confusing it with cruelty, lack of compassion, and mercilessness.

Biden is cut from a very different cloth. Perhaps that is in part due to his fundamentally different psychological makeup, parental attachments, and formative years—for example, Biden’s lifelong struggle with stuttering, for which he was at times fiercely mocked, even by a nun who was also his teacher.

But just as surely, Biden has been shaped by his well-documented encounters with great loss and suffering—the death of his first wife, Neilia, and his 13-month-old daughter, Naomi, in a 1972 car accident, when Biden was 30 years old, and the death of his oldest son, Beau, from brain cancer in 2015.

Biden’s wife, daughter, and son were, by all accounts, people whom he cherished; he delighted in their company, and their deaths were grievous blows. His Catholic faith started to buckle. (It eventually recovered, and is now a source of great comfort to him; these days, he is fond of quoting Kierkegaard, who said, “Faith sees best in the dark.”)

After Biden’s wife and daughter were killed, he wrote, “The pain cut through like a shard of broken glass. I began to understand how despair led people to just cash it in; how suicide wasn’t just an option but a rational option.”

That tragedy became an inflection point. Biden could have been broken by these losses; instead, they deepened him. “One key to life is tying periods of suffering to a narrative of redemption,” a friend once told me. Biden, facing nearly unbearable losses, used them to find greater meaning in his life, to find a narrative of redemption.

“I wanted to give people hope,” Biden said in 2017, in talking about his book Promise Me, Dad. “That there is—through purpose, you can find your way through grief.”

Through that journey of grief, Biden not only found purpose; he also forged within himself greater empathy and compassion. He is a man acquainted with the night; his own wounds made him better able to identify with the affliction and agony caused by the wounds of others.

“When I talk to people in mourning, they know I speak from experience,” he’s said. “They know I have a sense of the depth of their pain.”

There are countless stories of Biden reaching out and offering a listening ear, comfort, and counsel to those caught in the vise grip of grief. Over the years, he has become almost a pastoral figure to friends, colleagues, and even strangers. Biden has delivered nearly 60 eulogies; he has become an “emissary of grief,” in the words of The New York Times’ Katie Glueck and Matt Flegenheimer.

“Joe Biden has almost a superpower in his ability to comfort and listen and connect with people who have just suffered the greatest loss of their lives,” Delaware Senator Chris Coons told Politico’s Michael Kruse.

Those are beautiful qualities to be found in an individual; they can also be important, even essential, qualities in presidents. At moments in the life of a nation, the president is called upon to give expression—in his words and through the grace and dignity with which he carries himself—to the sensibilities and emotions of a nation. They may be grief; they may be fear; they may be joy. But a president’s job is not just to express a kaleidoscope of people’s passions and feelings; it’s to properly channel them, to refine and elevate them, and to put them within a proper context. A president should connect with who we are, but also make us better than who we are. We need leaders who embody, even if imperfectly, our better angels.

The person who may have best captured how this moment has found Joe Biden is the comedian and occasional social commentator Jon Stewart.

Last summer, Stewart said that America was in terrible anguish—fearful, angry, and in pain. Biden was not in the top tier of candidates whom the progressive Stewart wanted to win the Democratic nomination. But when he sees him, Stewart said, “I see a guy who knows what loss is, who knows grief. And I think that kind of grief humbles you.” He added, “There’s a humility to the randomness of tragedy that brings about a caring that can’t be faked, and it can’t be contrived.” Stewart went on to talk about America’s need for a leader who understands that we have to connect on a much deeper level than we have.

“I actually believe something in [Biden’s] life experience can benefit this country at a moment it desperately needs it.”

So do I.

I say that as someone who, in the past, wasn’t all that impressed with Biden. I disagreed with him on some important policy matters, as I do now, and I thought he was a somewhat average political talent. What stood out about him was his longevity more than his achievements, as well as how obviously well liked he was by his colleagues, including—and sometimes especially—Republicans.

But watching Biden conduct himself during this campaign, which has been superbly run, and learning more of his story, has changed how I view him.

In a different time, with a different president, Biden would not stand out. But Trump’s particular maladies have created a moment in which Biden’s greatest strengths as a person are most needed by the nation. Things like decency, honor, respect, and, yes, empathy are on the ballot. From the start of this election, Biden understood the theory of the case. He understood what the nation was thirsting for.

This doesn’t mean Biden won’t make mistakes if he is elected president; he most certainly will. It doesn’t mean that I won’t disagree with some of what he does; I most certainly will. But what it does mean is that some measure of integrity and dignity will return to the presidency; that the unprecedented, intentional effort by an American president to divide us will end; and that a person who has experienced grief and grace in his life can use what he’s learned to help bind up our wounds.

That isn’t everything we need in a president, but it is something we badly need. In the winter of his life, years after most people thought his political career was over, Joe Biden may be just the person America needs.

Peter Wehner is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes widely on political, cultural, religious, and national-security issues, and he is the author of The Death of Politics: How to Heal Our Frayed Republic After Trump.