Published October 15, 2020

A strange ritual is being conducted by the United States Senate this week. Senators have been taking regular turns refining talking points into sound bites and cable news video clips, which will later be spliced into campaign ads and fundraising videos. The ostensible reason for this tedious rite is the vetting of a nominee for the vacant seat on the Supreme Court: Judge Amy Coney Barrett. Such confirmation hearings have become a farce.

Judge Barrett, for her part, has demonstrated grace and patience, and flashes of legal brilliance, during the proceedings. If confirmed, Judge Barrett will be the sixth Catholic member of the Supreme Court. Judge Barrett’s Catholic faith – and her membership in the ecumenical charismatic group, People of Praise – has been the subject of much discussion since she was nominated and confirmed to the Seventh Circuit back in 2017.

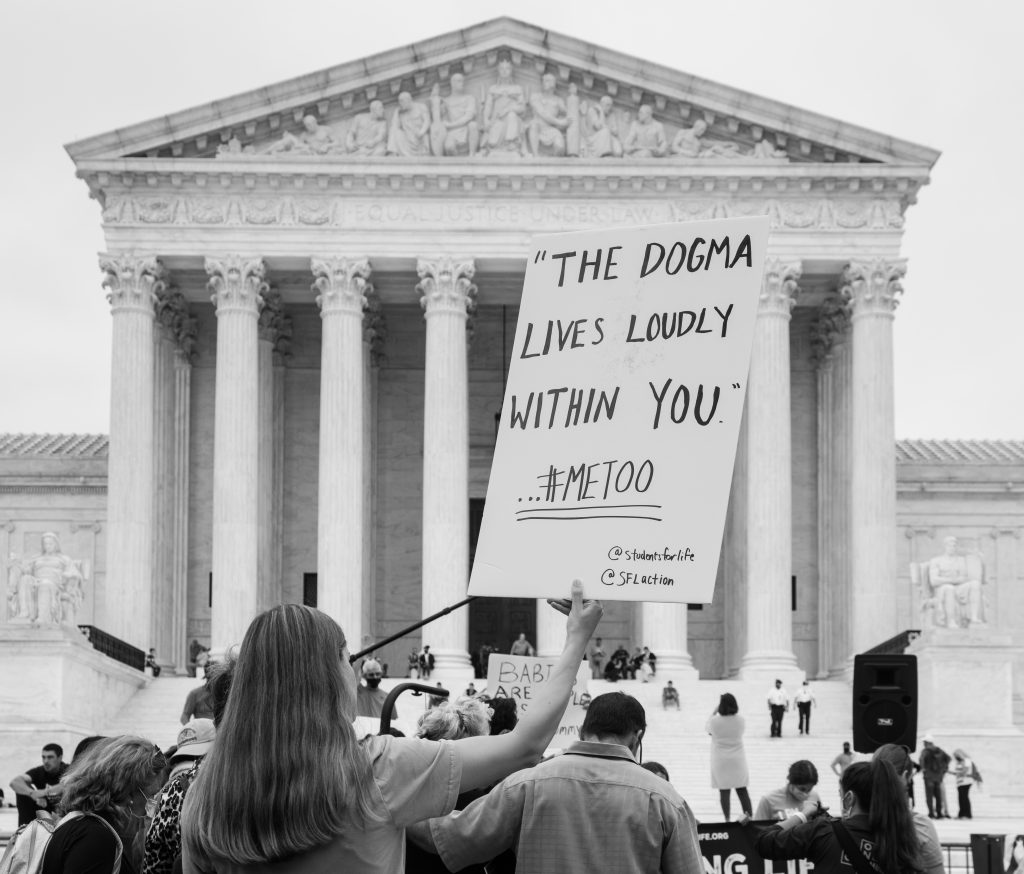

During those hearings, Senator Diane Feinstein infamously sneered that “the dogma lives loudly” in Amy Coney Barrett, who is the mother of seven. Barrett has been subject to a vile stream of abuse and ridicule online and from much of the press.

While the Constitution prohibits religious tests for office, the “volume” of one’s religious belief still seems to matter to some. Catholics are welcome, so long as their words and actions don’t proclaim certain dogmas too loudly.

The distinctiveness of Barrett’s faith – and the consternation it causes among the champions of certain secular pieties – is refreshing. It also underscores the indistinctiveness of so many Catholics who hold public office.

The uncomfortable truth is that “being Catholic” in the United States no longer indicates a distinctive approach to politics. Even more concerning, from a Catholic point of view, is that “being Catholic” in America no longer indicates a distinctive set of religious practices. Indeed, the “mere” fact that someone is Catholic tells us next to nothing about the content of his or her religious beliefs.

James Joyce’s line – “Catholic means ‘Here comes everybody’” – is a good reminder that our tribe has always been a varied and motley one, filled with sinners and saints alike. Still, the state of the Catholic belief in the United States, and thus the state of Catholic witness in public life, seems particularly degraded these days. This is one reason why “Catholic” so often comes with a modifier – liberal Catholic, conservative Catholic, JP2 Catholic, Pope Francis Catholic, Catholic in the Jesuit tradition, etc. The modifiers are needed to convey any meaningful distinction.

The necessity of such modifiers should give us pause, especially when we uncritically apply them to ourselves. Recall to mind St. Paul’s chastisement of the Corinthians for their worldly way of thinking: “Whenever someone says, ‘I belong to Paul,’ and another, ‘I belong to Apollos,’ are you not merely human?”

It is an interesting question to ask how we have arrived at this state of affairs. One could point to other ideologies, left and right, that slowly stripped away the distinctiveness of Catholic life in this country. (If one supposes, as some do, that four years of rationalizing bad behavior by this president has corrupted the consciences of some Catholics, imagine what four decades of rationalizing support for abortion has done.)

One could point to the years after the Second Vatican Council, when sacramental discipline collapsed amid social and cultural upheaval. One could blame bishops, who abdicated their responsibility to teach and govern, permitting their flocks to stray with impunity. There is probably a grain of truth in each of these explanations.

But we should be willing to acknowledge that Catholics in the United States lost our distinctiveness, not just because of something that happened to us, but because we chose to.

Elizabeth Bruenig, herself a Catholic, recently wrote about the unintended consequences of generations of Catholic striving to find a home in a Protestant America that was, for a long time, suspicious of Catholics. In short, we lost our Catholic distinctiveness because we wanted to fit in: “Perhaps Catholics have earned the right to no distinction, the privilege of blending seamlessly into the social and political landscape of the United States, the freedom of having no special moral obligations. And what a wide, barren, featureless liberty it is.”

Like anyone else, we Catholics are shaped by the circumstances in which we find ourselves. For Catholics in America, that means a culture once dominated by Protestantism and largely dedicated to a political creed (liberalism) toward which the Church has long been wary. American bravado and individualism may have served early immigrants well and fueled the pioneer spirit. But these same typically American traits have proven particularly corrosive to the citizens of a superpower as affluent and technological as ours has become, especially in the years since World War II.

The effect on the Catholic faith has been corrosive, too. Call it inculturation. Call it syncretism. Call it, as Pope Francis has, the triumph of a “technocratic paradigm” which has deluded us into believing that ordering human society is about the technocratic exercise of power, when it’s really about the proper ends of human existence, both natural and supernatural.

If being Catholic isn’t a sign of contradiction to the worldly orthodoxies of our time, then surely, we are doing something wrong. If we see the Church as a compassionate NGO, as Pope Francis has warned, then we are proclaiming, not Christ, but a “demonic worldliness.” If our Catholic faith is indistinguishable from the spirit of the age, we are like salt that has lost its flavor.

And that brings us back to the kabuki theater of the Senate confirmation hearings. The hearings are not about justice, or the nominee’s qualifications, but about power: power over life, over the family, over society, over nature, and over the Church. Judge Barrett – by the priorities she embodies and, yes, the dogma she proclaims – has convinced her opponents that her confirmation would be an intolerable obstacle to their exercise of that power.

Would that more of us Catholics were so intolerable. Our country would be better for it.

Stephen P. White is executive director of The Catholic Project at The Catholic University of America and a fellow in Catholic Studies at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.