Published September 20, 2019

Three Democratic candidates for president — Julián Castro, Cory Booker, and Marianne Williamson — have declared support for the idea of slavery reparations. A number of others have said they’d vote for a bill sponsored by Representative Sheila Jackson-Lee (D., Texas) to create a “commission to study and develop reparation proposals for African Americans.” Still other candidates have been vague (Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, Beto O’Rourke), while Elizabeth Warren has called for a “national, full-blown conversation about reparations in this country.” Oh, a conversation.

A Washington Post piece examining the tensions between black Americans on the question offers a glimpse of why this idea is terrible. It’s a profile of William A. “Sandy” Darity, a professor of economics at Duke, and leader of the “Planning Committee for Reparations,” a group of academics who are attempting to create a program to implement reparations. They envision a plan that would offer cash payments to all African Americans who can 1) prove that they are descended from someone enslaved in the United States and 2) have identified as black in public documents for at least ten years.

This, as you can imagine, has engendered some raised eyebrows. “It’s extremely difficult to separate classes of black people,” objects Nkechi Taifa, a D.C. “activist” (per the Post) who supports the idea of reparations for all black people. “The idea that unless you can actually trace your family directly to a slave that you haven’t been subject to the legacy of slavery is a bunch of hogwash.”

There it is, the ticking time bomb of intra-group resentment that reparations talk ignites. About 10 percent of black Americans today are foreign-born. The number of blacks who are children and grandchildren of immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean is even larger and includes some outstanding achievers, including Malcolm Gladwell, Colin Powell, Patrick Ewing, and Barack Obama. As Taifa hints, when you start handing out checks based on descent from enslaved people, you’re implying that other African Americans have not had to overcome the “legacy” of slavery.

If the concept of reparations incites enmity among different groups of black people, just imagine how much tension it will stoke among other groups.

My sense, from talking with people who support reparations, is that it really isn’t about the money. It’s about recognition. What they really want is for Americans to acknowledge that blacks have been uniquely oppressed and persecuted in U.S. history. That is not something that most Americans would deny. Some small-minded people do, of course. But public policy for the past 70 years has arguably been dominated by debates about how best to remediate the handicaps that have been imposed on African Americans (as well as by resistance to such efforts).

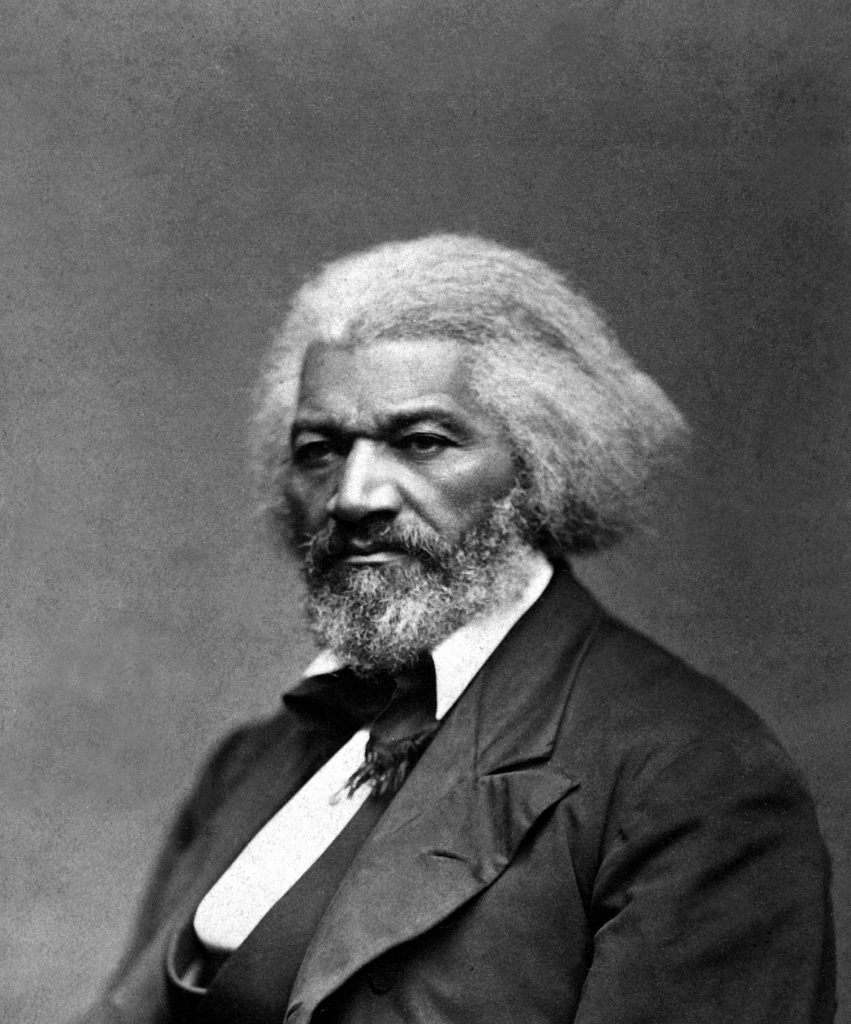

Four hundred years after the first slaves were brought to this land, it remains a painful and difficult subject. I’ve just read David Blight’s Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. If you want to chill your blood, read Douglass’s indictment of American hypocrisy in his speech “What, to the slave, is the Fourth of July?” A former slave himself, Douglass was, remarkably, one of this nation’s severest critics and greatest champions.

Julián Castro declares that “our country will never truly heal until we address the original sin of slavery.” Castro speaks of it as if we didn’t fight a crushing civil war; as if we didn’t adopt affirmative action in education, jobs, the military, banking, housing, and more; as if our entertainment and culture were not drenched in race consciousness; and as if we didn’t elect an African-American president.

In fact, as fans of reparations are slow to recognize, we suffer not from too little but from too much race consciousness. In the age of Trump, the percentage of whites who say that whiteness is important to their identity is rising. There is a cost to pitting Americans against one another in an oppression sweepstakes. Of course blacks suffered incalculably during slavery (and after). But their pain cannot be healed by payments to their descendants any more than dead slave owners can be punished by taxes on their progeny. We cannot cure one injustice by imposing another (even if a far lesser one). And critics who object that Native Americans, Asians (see, for example, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882), and others have endured their share of misery are correct. Who will parse exactly how much cash their great- or great-great-grandchildren are entitled to?

History is too vast and too complicated to allow for tidy accounting of sins and victimization. What we owe to one another is, as Frederick Douglass charged us 167 years ago, to stand by our founding ethos. “Stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost.”

Copyright © 2019 Creators.com

Mona Charen is a syndicated columnist and a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.