Published January 11, 2019

More-stringent work mandates are necessary, but only for federal programs that discourage workers from finding employment. Here’s why:

Public-assistance programs have little effect on the unemployment rate when recipients are outside the labor market — for example, retirees (receiving Social Security and Medicare benefits); people with disabilities (disability benefits, workers’ compensation and Supplemental Security Income); veterans (veterans’ benefits); and dependent children (family, dependent and survivor benefits). But such programs reduce recipients’ rates of participation in the labor force.

I recently tested the effect of all major federal and state-level public-assistance programs on the U.S. civilian unemployment rate and labor force participation rates by applying Rueff’s Law of Unemployment.

In 1925, the French economist Jacques Rueff showed that in Britain, the collision of sharply fallen prices and the recently instituted (1911) unemployment “dole,” fixed at so many shillings per week, caused the chronic unemployment of the 1920s. As prices fell, the “real” or inflation-adjusted wage rate rose in step with the unemployment rate. This relationship was found in many other countries as well and was called Rueff’s Law of Unemployment.

To what extent social benefits discourage work varies widely and depends heavily on the conditions under which recipients receive assistance. For example, unemployment insurance and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC),

a tax credit for low- and moderate-wage workers, differ in that the former is conditioned on unemployment and the latter on employment.

Unemployment insurance benefits raise the unemployment rate by more than 4 percentage points for each 1 point that those benefits make up the share of national income.

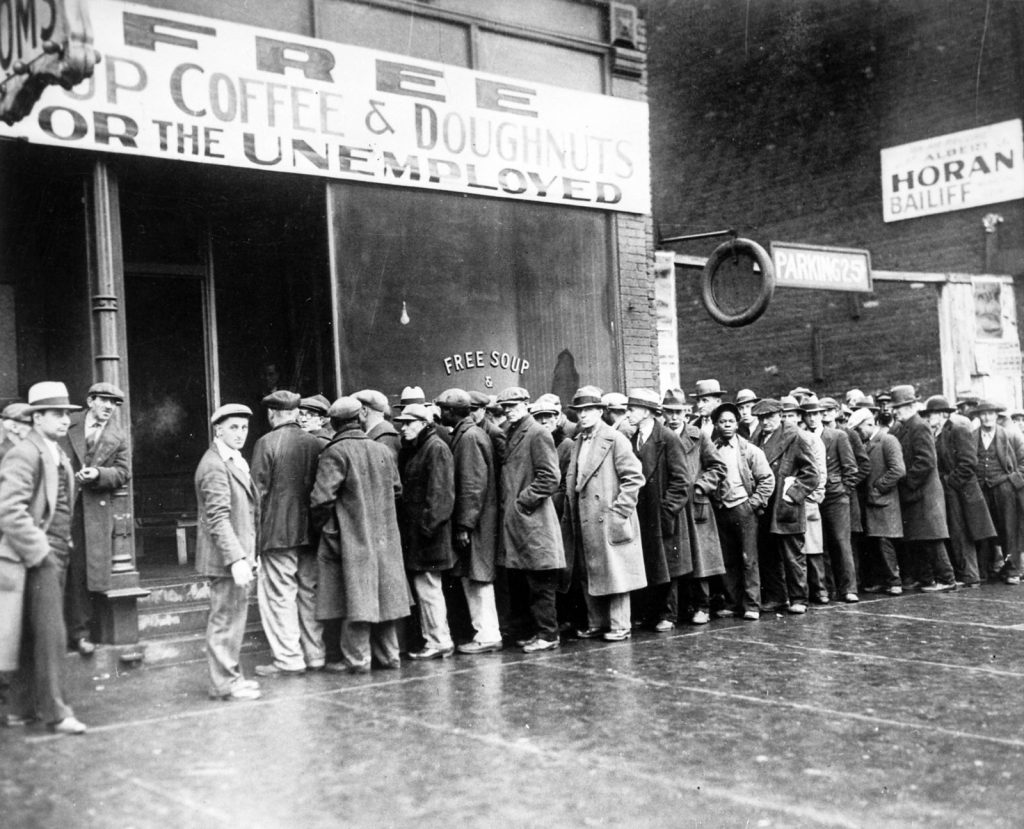

The jobless rate has soared each time Congress has lengthened the period during which unemployment benefits may be received — most recently when, in response to the 2007-09 recession, Congress extended the period from 26 weeks to 99 weeks. After the law authorizing extended benefits expired, the unemployment rate fell sharply.

Work mandates are especially necessary in the food stamp program because food stamps have almost twice the disincentive effect of unemployment benefits. Unemployment insurance benefits, meanwhile, should always remain at no more than 26 weeks.

It is natural to feel compassion for those less fortunate than we are. But benefits should be concentrated in programs that have the least disincentive effect on recipients’ employment in the labor market. Work, after all, leads to higher incomes and greater human dignity.

John D. Mueller is the Lehrman Institute Fellow in Economics and Director of the Economics and Ethics Program at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.