Published September 9, 2021

The 20 years since 9/11 have produced two tragic outcomes: Afghanistan has reverted to the Taliban, and—unexpectedly—America has disappeared down a rabbit hole. Barbarism, in different forms, is on the march in both countries.

Americans intervened in Afghanistan in order to deny safe haven to terrorists and somehow to change that country for the better. Alas, at the end of the 20 years, Afghanistan finds itself back in the seventh century. It was America that got changed, almost beyond recognition. Americans split down the middle and became their own worst enemies. Their politics grew hysterical and vicious and surreal. They took to despising one another.

In the early days of George W. Bush’s presidency, everyone agreed that Islamist terrorism was the great threat. In the early days of Joe Biden’s presidency, to hear one side tell it, the most dangerous menace turns out to be white Americans—whiteness itself. And “systemic racism.” It’s worse than that: one might say that the great Satan is American history itself, which from the start (from 1619 on) has been the story of a crime. The indictment is comprehensive: The bizarre theologies of wokeness enjoin a thousand heresies—“cultural appropriation,” disrespect for someone’s “pronouns,” and other offenses that any sane society would find hilarious, except that in these days, since the turning of the American lake, such matters are deadly serious. There is no more humor in the kingdom of the woke than there was in Walter Ulbricht’s East Germany in 1954. People lose their jobs, their careers—they are ostracized and publicly shamed—for saying something regarded as incorrect.

Back in 2001, Americans had a sentimental notion of encouraging Afghans’ freedom (the rights of women, for example). This was an old-fashioned impulse. But back in the homeland, the “elites”—in the universities, the media, Big Tech, government, big corporations, and cultural institutions such as foundations, museums, and symphony orchestras—were busy throttling American freedoms of thought and speech in the name of social justice. Forget merit, which is racist; “equity” is all. Race and sex, which the woke call “gender” so as to disentangle it from the reactionary realities of nature and make it seem, instead, fluid and discretionary, became neurotic obsessions. Denigrating and sometimes defunding the police have left major American cities increasingly defenseless against crime. As for gender, it has become woke writ that men may have babies. Out of wokeness, there is always something new and strange and marvelous. The concept of woman and motherhood, sacred once, is obsolete.

Are things in America as bad as all that? Are they worse?

Over the Labor Day weekend, the programmers at Turner Classic Movies, with a fine sense of mischief, showed Gunga Din. The movie cast a goofy, archaic light upon what had just happened in Afghanistan.

With the Americans gone back over the horizon and the Taliban donning captured U.S. combat gear and taking up their sharia whips as they returned to power after two decades in the hills, I found myself watching as Cary Grant, Victor McLaglen, and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. (the Three Stooges by way of Rudyard Kipling, the British Raj rollicking along as manly slapstick) brought the story to a much happier ending than the one that President Biden improvised. Kipling’s sergeants subdued the murder cult of Thuggee up on the Northwest Frontier of India, close by Afghanistan, and restored order and pipping good cheer to the Empire. The character actor Sam Jaffe, wearing no more than shoe polish and a diaper, appeared in the title role. The Thuggees could just as well have been played by the Taliban.

Unlike those shown on Turner Classic, the scenes around Hamid Karzai Airport in August suffered from the inconvenience of being real; yet they had some of the atmosphere—the style, the imagery—of the mayhem around the Thuggee temple in the movie. Except that, in 2021, there were enormous American airplanes roaring off to Doha; and there were no bagpipers to play “Bonnie Charlie’s Gone Awa’.” Instead of the happy denouement of rescue, the scene at the Kabul airport was drenched in horror and panic and the knowledge of betrayal. The Americans left Afghanistan, under the Taliban’s deadline, with a frantic, shameful efficiency.

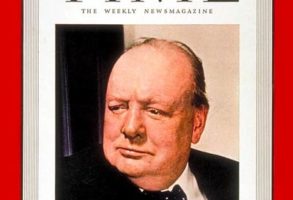

I thought back to the shock that precipitated the Americans into their longest war. On that day, September 11, 2001, with the television on the other side of the room endlessly replaying video of the hijacked planes hitting the towers and the towers’ collapse, I wrote a bloodthirsty essay for a special issue of Time. The headline on the piece said, “The Case for Rage and Retribution.” I wrote it in a fury—angrier, I suppose, than I have ever been—and finished it between noon and one in the afternoon. Time’s special issue closed that evening. Americans took the attack personally, viscerally, and felt as bloody-minded as Teddy Roosevelt: Pedicaris alive or Raisuli dead! Within weeks, President George W. Bush sent the American military into Afghanistan. Could he have acted otherwise? Of course. What did we want? “Rage and Retribution?” Revenge? Afghan democracy? A new and grateful friend? Rare earth metals?

Fast-forwarding through two Bush terms and eight years of Barack Obama and four of Donald Trump brings us, glumly, to the present reality of Joe Biden—brittle and grumpy and beady-eyed even in the early months of his term. It’s been a long time since the heroic Biden stood up to Cornpop or channeled Neil Kinnock. Was Afghanistan another Vietnam? Close enough. There’s plenty of blame to go around for everyone—but especially for Biden in the way he mismanaged the exit. Losing expensive wars in faraway countries has gotten to be an American habit. Moral colonialism—missionary work undertaken at great expense of American money and blood—hasn’t worked.

How should this sort of thing be done? Can it ever be done well? Maybe not. I recalled Evelyn Waugh’s classic and comic 1937 novel about journalism, called Scoop. Lord Copper, the nitwit press lord, publisher of the Daily Beast, is speaking to the paper’s garden columnist, William Boot. Boot, whom Copper has mistaken for a different writer with the same last name, is about to depart to cover the situation in Ishmaelia. Copper advises him to “take plenty of cleft sticks” with which to send back his dispatches. His final instructions: “The British public has no interest in a war which drags on indecisively. A few sharp victories, some conspicuous acts of personal bravery on the patriot side, and a colorful entry into the capital. That is the Beast policy for the war.”

In and out! Ronald Reagan’s Operation Urgent Fury began at dawn on October 25, 1983. The invading force—elements of the 75th Ranger Regiment, the 82d Airborne, the Army’s rapid deployment force, Marines, Army Delta Force, Navy SEALS and others, a total of 7,600 Americans—made short work of Grenada’s Communist New Jewel Movement government. The operation, over in a day, liberated 631 American medical students trapped at the St. George’s Medical School. Thus did Reagan rescue the little Caribbean island of Grenada—the world’s second-largest producer of nutmeg, after Indonesia—from Communist tyranny and put an end to what was called America’s Vietnam Syndrome. “Our days of weakness are over,” Reagan told the nation. “Our military forces are back on their feet and standing tall.”

In Afghanistan, 20 years is nothing. Strangers come and go: Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, the Persians, the Sikhs, the British, the Soviets.

The Americans also came. They just left. They can’t say they weren’t warned—by Kipling, for one:

Now it is not good for the Christian’s health to hustle the Aryan brown,

For the Christian riles, and the Aryan smiles and he weareth the Christian down;

And the end of the fight is a tombstone white with the name of the late deceased,

And the epitaph drear: “A Fool lies here who tried to hustle the East.”

American presidents should read more poetry and satire and books of history before they go to bed or make big policy decisions. George W. Bush was too eager to go into Afghanistan. Joe Biden was too eager to get out. It’s over, in any case; Biden figures everyone will forget about it pretty soon. He’s probably right. Still, it’s not easy to respect someone who walks away from a mess he helped to create and mutters something about how you can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.

Lance Morrow is a Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.

Lance Morrow is the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His work focuses on the moral and ethical dimensions of public events, including developments in regard to freedom of speech, freedom of thought, and political correctness on American campuses, with a view to the future consequences of such suppressions.