Published February 9, 2018

Henry Luce’s America was your grandfather’s country. It met its demise around the same time that Luce himself did, in the late 1960s. In our time, it would reappear only to be satirized as a remnant of the age of Mad Men—the regime of white, male, privileged characters who drank like fish and smoked like chimneys and treated women as if, officially speaking, they did not quite exist. On the other side of the barricades, the memory of that country is conjured up, in a spirit of defiant nostalgia, in order to suggest the meaning of Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again.”

At the time, it did not occur to Luce and his men to think of themselves as white or male or privileged; such politics of identity lay in the future. Luce was a journalistic genius and Presbyterian missionary’s son, born in China, and his sense of the world was portentous, preoccupied by world wars and the rise and fall of empires. His enemies on the left—including a number of his own editors and writers—considered him a horse’s ass who was either sinister or endearing, depending on the issue at hand. In the early thirties, one of his young writers on Fortune, James Agee, would sit late at night in his office, high up in the Chrysler Building, drinking bourbon, listening to Beethoven on a phonograph, and nursing a fantasy of walking down the hall to Luce’s office and shooting him in the chest with a pistol. Agee imagined that all the other writers and researchers would peek their heads out of their offices and, realizing what Agee had done, would sing and dance like munchkins: The wicked witch is dead! Luce put up with a great deal of this, considering it to be part of the price he paid for quality. (“Goddamn Republicans can’t write,” he said.)

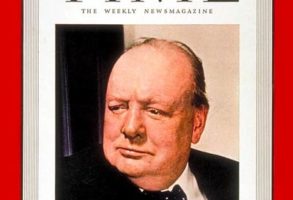

Luce was a complex man, much underestimated, and almost entirely forgotten now. He worshipped heroes; he smoked incessantly; he dined on ideas. One of his favorite Time-Life writers—until the Hiss case came along in 1948—was the doomy, melodramatic apostate Communist Whittaker Chambers, whose anguished sainthood appealed to Luce’s memory of a religious childhood.

Mad Men was filmed in the Time-Life Building in New York. The advertising executive Don Draper’s office reproduced, in eerie detail, my senior editor Gus Daniels’s office as it appeared when I arrived at Time in summer 1965. One Saturday night that summer, we made last-minute changes on the “yellows” (the final edit before a story went to the printers) and wrote captions and waited for “checkpoints” to clatter in from correspondents in the bureaus. All this was done on paper: computers lay far in the future. Researchers, all women, hurried in and out of the room with fixes—“red changes”—on the copy. We were gathered in Gus’s office and drank Johnny Walker Red or Bombay gin (the Luce operation was famous for its good liquor).

On this particular Saturday night, we watched the Watts riots on Gus’s color television set. Watts was the first of the great summer riots of the 1960s. We watched mostly in silence, except for the rattle of the ice in our glasses. We’d had three or four hours’ sleep the night before—the usual routine toward the end of the editorial week. The Tower Suite sent down a catered roast beef dinner, and we went off to eat at our desks. Accounts of the old days at Time always make much of the liquor carts and the catered dinners and the fancy expense accounts, and all of that was true. But the work was hard and the standards, on the whole, were exacting and obsessive; and the editors, sometimes spectacularly neurotic (one of them ate pieces of paper when he was agitated), were also intelligent and sometimes learned, and the people one worked with were, many of them, splendid and gifted and eccentric and irreplaceable. Time Inc. was an interesting and demanding universe.

I worked at Time in the post-Luce years, after Hedley Donovan had taken over from Luce, and, after him, Henry Grunwald. In many ways, the magazine improved. Grunwald civilized it, gave it a more complex voice.

If we had been more alert and thoughtful about the riots and the television coverage that night in 1965, we might have felt a tremor—might have had a distant intuition of the end of days. In years to come, Time Inc. would merge with Warner, and then Time Warner would merge with AOL (a disaster). The technology and the very metaphysics of journalism would change, irreparably. Everything would change. It had started.

Luce had retired a year earlier, in 1964, to a house on the grounds of a golf course in Phoenix. Every now and then he reappeared in the building, like the ghost of Hamlet’s father. There would be a stir along the corridors. He would vanish upstairs to have lunch with the editors in a private dining room. I never met him. He was a sort of hallucination. He would die in Phoenix in February 1967, just as America sank irrevocably into Vietnam. But even with Luce gone, his great work, Time Inc., remained the superpower of print. When I sat down in my office on the 25th floor to write a story, without byline, on a smudged Royal desk model typewriter, I was a voice in the chorus. (Bylines would come with Grunwald). I consoled myself with the knowledge that my words would go out to a readership of many millions. A motorcycle courier would speed an early copy of the magazine (a “makeready”) to the White House on Sunday night. Lyndon Johnson would wait up for it in his pajamas and pore over the magazine; if he read something he didn’t like, he would phone Hugh Sidey, Time’s White House correspondent, and wake him up and yell in his ear. Goddamn it, Sidey! You bastards.

I knew that my story would be read by every mayor and governor in America, by every senator and congressman, every justice of the Supreme Court—by the president of each corporation, by all who were in power in America, or wished to be in power; and by every lawyer, every doctor and dentist, and by their patients in the waiting room.

That was Time Inc.’s power—the influence of Time and Life, primarily, preeminent magazines in America’s long golden age of magazines that ran from early in the twentieth century until, let us say, the folding of Life in 1972. Luce was the Henry Ford of magazines. Born in exile, a world away from his birthright, he would use his magazines to invent, or reinvent, America, according to his own moral design. He sentimentalized Oskaloosa, Iowa, and said that he wished that it had been his hometown.

He and his partner/rival Briton Hadden came out with the first issue of Time in March 1923. Hadden died (of a blood infection) in 1929. Just at the start of the Depression (bad timing, one would think), Luce came forth with the opulent Fortune, which, in its early years, was arguably the best magazine ever published. Then in 1936, Time Inc. began publication of Life, another brilliant invention. Over the years, claimed Robert Hutchins, an educator and former chancellor of the University of Chicago, Luce’s magazines would have more impact on the American mind than the country’s entire system of public education. That may be true.

Now Time Inc.—only recently cast off in a pinnace from the mother ship Time Warner, which has elaborate twenty-first-century ambitions and came to regard magazines as a relic and a bother—has been sold to the Iowa-based Meredith Corporation for $1.8 billion, including $650 million put up by the Koch brothers. Some of the magazines will survive under the new ownership, some not. Costs and staff will be cut drastically. One of the new owner’s first acts was to remove the Time Inc. sign from the lower Manhattan building to which the magazines had repaired after being driven out of the Time-Life Building in midtown.

The stoats and weasels have taken over Toad Hall. The once-mighty imperial fleet will be broken up and sold for scrap. The ghost of Henry Luce (who wanted to be a poet when he was young) would think of Kipling’s “Recessional”:

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Ninevah and Tyre.