Published August 27, 2018

‘The Godfather” was the American dream enacted as organized crime. Donald Trump is the American president as crime boss—a sort of zesty travesty (zesty anyway for those who are not appalled). He gave an interview to Fox News in which he talked about people who flipped, about rats, in the Cosa Nostra sense of the word—he sounded like James Cagney or George Raft telling war stories about run-ins with the district attorney. Mr. Trump says he has many friends who were the victims of rats and flippers.

But you should remember that most people who read Mario Puzo’s book, or saw Francis Ford Coppola’s movie, rooted for Don Corleone and (though less enthusiastically) for Michael Corleone —and in any case not for the Senate committee or for the corrupt senator who woke up in a bloody bed in a Nevada whorehouse. The people loved the Don’s story so much they brought it back for encores—“Godfather II” and beyond. Audiences loved the smirk on Vito Corleone’s face when the terrified landlord spluttered, “De rent—stays-a like-a before!” And the widow kept her dog! Democrats should bear these things in mind.

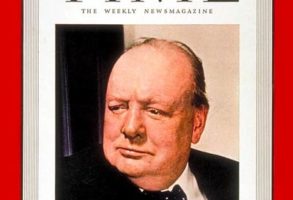

Presidents have their favorite movies. Nixon loved “Patton,” and he watched it as the prosecutors closed in. Mr. Trump is the Godfather. Let us have cartoons all around—fantasies of decisive autocrats.

Look at the president’s behavior from the Corleone point of view. The first premise held by Mr. Trump and his supporters—their entire philosophical basis and civic rationale—is that the American government and other institutions (universities, media, many big corporations) are gone, captured by Long March Progressives (people who, in the manner of ideologues, have no idea how odious they often seem in the eyes of perfectly decent people with different politics and different memories of the country) and by a Democratic Party that itself has become a sort of Cosa Nostra run along Maoist lines. By this logic, only an outlaw regime such as Mr. Trump’s can restore freedom, justice and the old ways. The Resistance is the Mob, and Mr. Trump represents the bracingly uncouth primacy of the earlier republic. The Trumpists are Russia’s Old Believers, and he is the archpriest Avvakum.

The left sees a different historical comparison. New York magazine’s Frank Rich, for example, refers to Mitch McConnell et al. as “the Vichy Republicans.” According to Mr. Rich’s analogy, embraced by many others on the left, American government has become the Third Reich. Donald Trump is indistinguishable from Adolf Hitler. Republicans who collaborate with the Trump administration are Marshal Pétain and his Vichy regime. They will face judgment when this is all over. They will be tried, they will have their heads shaved, and some will be hanged.

What we behold in all of this, inter alia, is the rancid denouement of the baby-boom generation. Donald Trump was born June 14, 1946. Hillary Clinton entered the world a little later, on Oct. 26, 1947. They were proto-boomers, among the earliest arrivals in the first wave of that vast generation that would go on to invent rock, drugs, sex, the iPhone and everything else that is wonderful. The boomers refreshed American exceptionalism. They represented a nation with the dew still on it, a new beginning, a miracle of history.

Who needs Lexington and Concord when you have Woodstock and Stonewall? Like the Clintons and Donald Trump, boomers are their own most ardent fans. Their overwhelming numbers have ensured that as they pass through history, they remain snug in a cloud of their collective self-regard. They generate their own publicity, then affirm its truth by believing it. The narcissist is his own best customer. (The Kennedys—who emerged in an earlier era and were immunized by Joseph Kennedy’s cynicism and money—were more realistic about their own hype.)

In the 1960s, battles among boomers were mostly sublimated in the overall boomer rebellion against their elders—their authority, their ways and their war. Boomers put off, for almost a lifetime, the intragenerational struggle that finally emerged in 2016. The dissident boomer elites won the wars of their youth; they triumphed when the war in Vietnam was lost, and they deposed two presidents, Johnson and Nixon. These were heady, Oedipal victories that exacted a high long-term price and, almost unnoticed, embedded in the boomer legacy a self-righteousness born of their own secretly perceived guilt, and a need to validate their dissidence by embracing a radical critique and a sort of institutionalized and theological mistrust of their own country.

The dissident boomers, to justify their rebellious indulgences, must maintain that the fathers needed killing, and, as a matter of fact, that America was wicked in its origins and remains wicked even now: racist, genocidal, sexist and unjust.

As they approached the end of their story in the 2010s, it made sense that Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton (boomer twins and opposites) would be the 2016 presidential nominees—or at least it made as much sense as the obsessive chic of transgenderism, or discretionary pronouns, or tattoos, or Bob Dylan as a Nobel laureate. The boomers invented themselves. They have their own ways of doing things. They are a universe floating in time and space, deaf to earlier cultural transmissions and to the lessons of experience.

By this time, they have grandfathered their peculiarities into American culture and politics and planted them deep in the minds of millennials and those even younger. There is no turning back. And that, in part, is how we have arrived at this interesting place in our journey.

Mr. Morrow, a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, is a former essayist for Time.