Published January 17, 2018

President Trump and Republican House and Senate leaders deserve credit for enacting the 2017 tax reform. But the specifics of that law indicate that it won’t have positive economic or political results to match President Ronald Reagan’s 1981 and 1986 tax reform bills or the Kennedy administration tax cuts of 1964-1965.

To understand why, we must grasp the economics and politics of taxation. Both go back at least to Aristotle in the 4th century B.C.

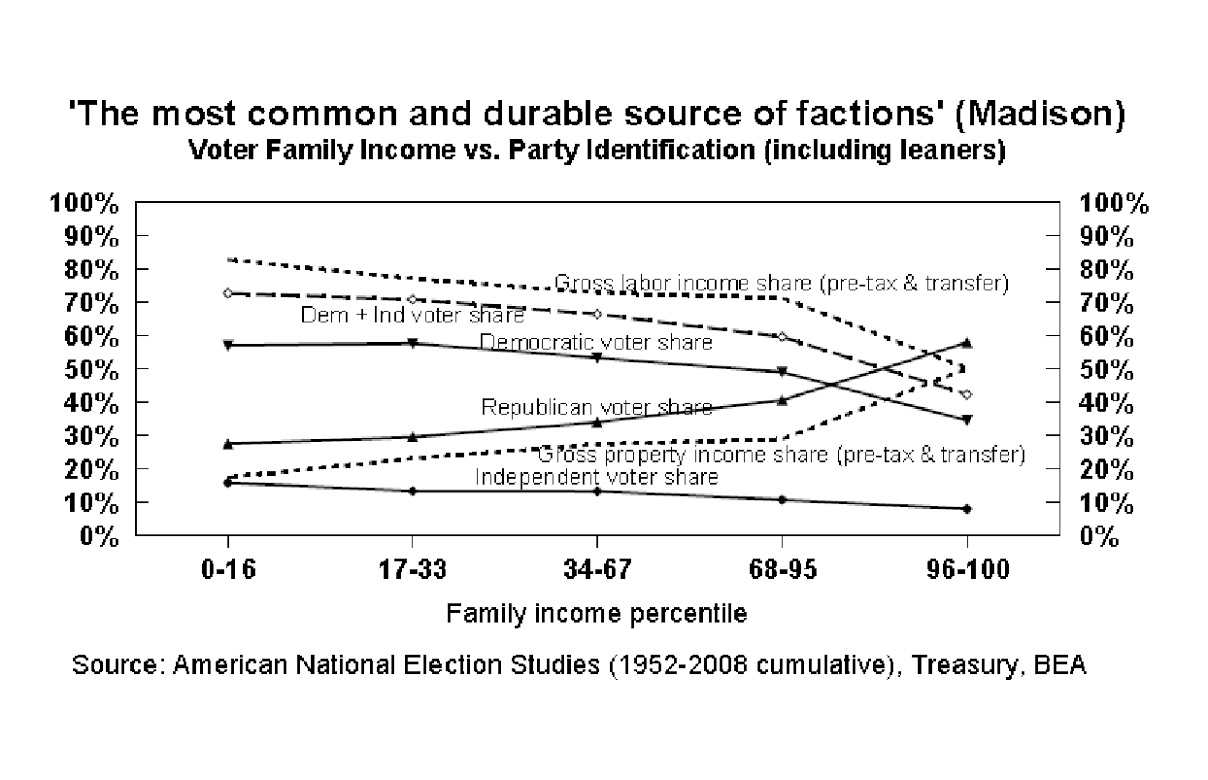

The first economic fact is that everyone’s income originates from two sources of wealth: people and property (or as Nobel laureate Theodore Schultz dubbed them around 1960, “human capital” and “nonhuman capital”). As a result, our gross income (before taxes and social benefits) entirely comprises labor compensation (wages, salaries, fringe benefits) and property compensation (interest, dividends, rents, royalties, capital gains). But we receive this labor and property income in different proportions, and these different proportions tend to determine our party affiliation and voting habits.

When discussing differences among governments, Aristotle concluded that the “real criterion should be property,” because “it is a matter of accident whether those in power be few or many, the one in oligarchies, the other in democracies. It just happens that way because everywhere the rich are few and the poor are many.”

James Madison extended Aristotle’s reasoning when he argued in Federalist No. 10: “From the protection of the different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.” Hence “the most common and durable source of factions has been the various and unequal distribution of property.”

As the first chart shows, generally speaking, voters who identify themselves as Democrats disproportionately receive labor compensation, and those who identify themselves as Republicans disproportionately receive property compensation, while independent voters fall in between. This pattern has existed as far back as we have data on income and voting. (The voter data come from the biannual American National Election Studies, and the income data from the U.S. Treasury. By focusing on income taxes, we leave aside federal social insurance, which follows a different economic and political logic, and was mostly ignored by the 2017 tax reform.)

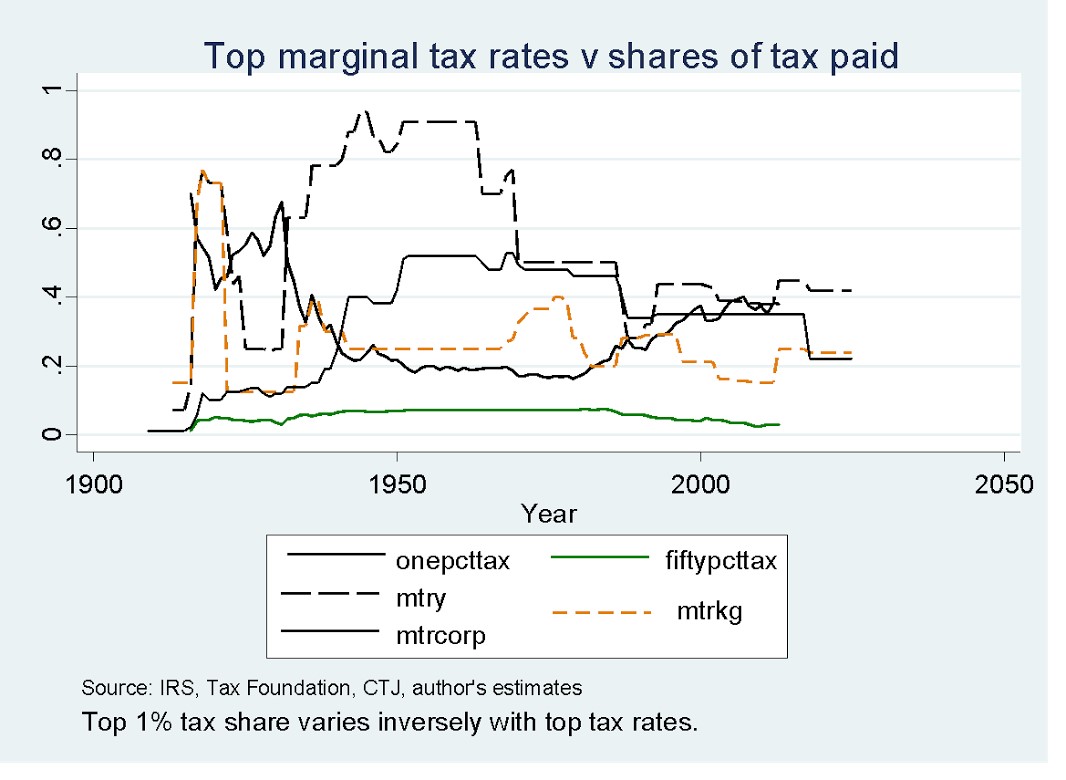

The economics and politics of taxation help explain the yo-yo pattern of top marginal income tax rates and the share paid by the top 1 percent of taxpayers, as reflected in the second chart. All major hikes in top marginal income tax rates have occurred under Democratic presidents (notably Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama), while significant reductions occurred mostly under Republican presidents (Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Reagan, George W. Bush, and Trump). The major Democratic Party exception was John F. Kennedy, whose plan cut top tax rates from 91 percent to 70 percent, and, among Republicans, the exceptions were Presidents Richard Nixon and George H.W. Bush (both were defeated or resigned).

These same facts also contradict the economic orthodoxy on taxation of both liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans.

On one hand, liberal Democrats’ politics of envy — seeking to reduce the share of income received by the top 1 percent — is politically self-defeating, because every major change in top income tax rates coincided with proportional inverse moves in the share of tax paid by the top 1 percent. This implies that there is a Laffer Curve for the top 1 percent, but not the top 50 percent or 25 percent, or perhaps even the top 10 percent of taxpayers.

On the other hand, the facts show that the reductions in top marginal income tax rates have done all the heavy lifting. When these are accounted for, reductions in tax rates on corporate income and capital gains have actually reduced the shares paid by the top 1 percent. This explains why the Reagan tax reforms were enacted only with the support of so-called “Reagan Democrats” in Congress, while not a single Democrat voted for the 2017 tax reform.

The major difference between the Reagan and Trump tax reforms is that while Reagan’s reforms cut the top marginal income tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent (to 33 percent including deduction phaseouts), they also equalized the top tax rates on all labor and property income. The 2017 tax reform cut the top personal income tax rate only slightly, while keeping the top tax rates on labor income substantially higher than on property income: the so-called “Warren Buffet’s secretary problem.”

Having participated in the successful Reagan tax reforms of 1981 and 1986, I was, relatively speaking, an optimist about the prospects for tax reform in 2017. When pessimists claimed a year ago that tax reform was dead, I argued that a tax reform bill would be enacted by Congress, a judgment that proved correct. But that same experience now suggests that the 2017 tax reform will have much smaller positive economic and political results — roughly in proportion to the much smaller reductions in the top marginal tax rates and failure to equalize the tax treatment of Main Street and Wall Street.

John D. Mueller is the Lehrman Institute Fellow in Economics at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and author of Redeeming Economics: Rediscovering the Missing Element. From 1979 until 1988 he was staff economist to the House Republican Conference, of which Rep. Jack Kemp of New York was chairman.