Published April 20, 2022

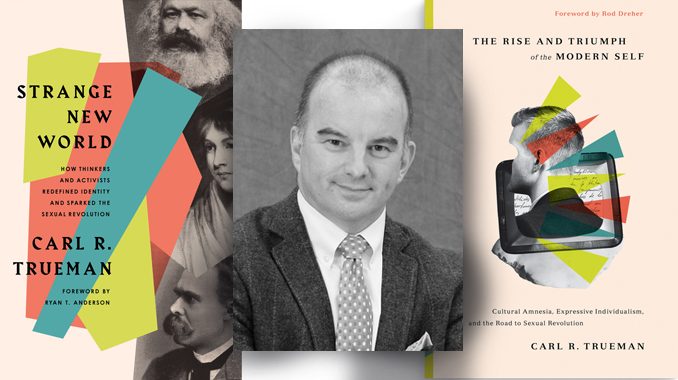

Dr. Carl R. Trueman’s book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution, published by Crossway in November 2020, has been a surprising best-seller: a 424-page, heavily footnoted work of history and philosophy taking on complicated and controversial topics with an admirable combination of clarity and charity. Lauded by Protestants (Trueman, who is is professor of biblical and religious studies at Grove City College, has served as pastor of Cornerstone Orthodox Presbyterian Church in Ambler, Pa) and Catholics alike, it has been praised by a variety of non-Christians as well.

In her CWR review of the book, Dr. Deborah Savage stated, “Without question, Dr. Carl Trueman has written a book of singular importance.” In my December 2020 review for the National Catholic Register, I noted that it is “a demanding work, full of historical details, philosophical explications, and cultural criticism. Despite that, it is a not only readable (setting it apart from many academic works), it is quite often both elegantly written and downright gripping, a sort of novelistic journey through the pathologies of modernism and post-modernism, a sort of historical and philosophical ‘whodunnit?’”

Now Crossway has published Trueman’s Strange New World: How Thinkers and Activists Redefined Identity and Sparked the Sexual Revolution, a much shorter (208 pages) and more accessible book that covers some of the same historical ground and cultural terrain. But even while aiming for a wider audience, this isn’t merely some sort of Cliffs Note approach. Dr. Trueman recently corresponded me with about his new book, why he thinks The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self resonated with so many readers, and cultural developments (or disintegration) over the past two years.

CWR: When we corresponded back in November 2020, your book The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self had just been published. Since then, it has become a surprise best-seller—a surprise because lengthy, detailed books with extensive footnotes about history and philosophy don’t normally sell well. Have you been surprised? How do you account for the book’s success?

Carl R. Trueman: I was indeed very surprised. I wrote the book in order to clarify for myself some of the strange pathologies of our current cultural moment. Clearly, I was not the only person wrestling with such issues. And, of course, the summer of 2020, with all of the social chaos that was unleashed on streets across the western world, raised the question of identity and meaning in powerful ways that made the book’s themes something of immediate relevance to many.

CWR: This new book is obviously meant to engage an even wider audience. In what ways does it introduce readers to the previous, longer work and how does it present new and additional material? If you had to express the goal of this work in a sentence or two, how would you state it?

Trueman: Much in the new book is a concise version of the larger book’s narrative of how the psychologized, sexualized self has come to grip the West’s moral imagination. But I also deal with some new themes. For example, I look at how Oscar Wilde is perhaps the quintessential sophisticated precursor of the modern self that finds its fulfillment in sexual transgression and public performance. Sadly, of course, most modern selves lack Wilde’s wit and deep grasp of Western culture.’

I also address the issue of the collapsing confidence in the nation state and the role of technology in reshaping our relationship to the world. Both of those are key issues in our current context, as the worldwide appeal of the BLM protests indicated.

CWR: You begin with an emphasis on the modern understanding of “self”. Why is this so key to understanding the sexual revolution in general and the triumph of transgenderism specifically?

Trueman: The self – that intuitive understanding we have of who we are – shapes how we intuitively relate to the world around us and that includes not simply other people but even our own bodies. The modern self sees itself as autonomous, free to shape its own identity and destiny, and not subject to some objective moral universe, conformity to which is required for well-being. That obviously affects how we understand the purpose of sex: is it something that fulfills a larger teleological purpose (sealing a lifelong union between one man and one woman; procreation) or is it simply a form of pleasurable recreation?

As to transgenderism, this is arguably the most radical form of expressivism thus far: even our own bodies are at best raw material for self-creation, at worst obstructions to us being who we really are. Hence, we find that our current culture finds to be plausible such nonsensical statements as ‘I am woman trapped in a man’s body.’

CWR: You provide a short but important introduction to thinkers including Descartes, Rousseau, Hegel, and Nietzsche, among others. Most people today, it’s fair to say, haven’t read the works of those thinkers. So what’s the connection? Is there really a lineage from those men, writing many decades (or centuries) ago, to 2022?

Trueman: All of these figures give self-conscious voice in their different ways to assumptions that make up the intuitive notion of the modern self. Examining their thought thus allows the reader to understand the nature and implications of a conception of selfhood that most of us simply take for granted.

What binds them together is a focus on human psychology in a manner that grants authority to our inner space. And it is that authorizing of the inner space, of our thought and feelings, that really marks the modern self off from its predecessors.

CWR: You write about sex “becoming political”. What are some aspects and key features of that process?

Trueman: The key element here is Sigmund Freud’s view of human beings as defined by the nature and direction of their sexual desires from infancy onwards. That move turns sex from something that humans do into something that they are.

Now, very few people read Freud today and fewer still find his arguments compelling. But the idea that we are our sexual desires and that satisfying those sexual desires is central to personal fulfillment is a powerful, plausible and rather attractive myth – and one preached by countless movies, sitcoms, commercials etc. We all know that the erotic is a very powerful part of the human experience – cultural artifacts from Genesis through the Iliad to the latest Hollywood offerings all testify to this.

And once sex becomes identity, then sexual codes move from being rules about what you can and cannot do to rules about who society will or will not let you be. Hence we have the last fifty years of battles over LGBTQ+ rights.

CWR: Technology is, as you note, a huge factor. What are some of the ways that technology, in recent decades, has shaped and facilitated sexual revolution?

Trueman: Technology shapes how we imagine the world and our place within it. And the more sophisticated and all-pervasive the technology, the more we are inclined to imagine the world as mere raw material over which we can impose our will and our control.

Thus, easy access to contraception, antibiotics, and abortion has allowed society to imagine that sex can be just a pleasant recreation. One hundred years ago that was not the case: sex was costly and risky and it would have been impossible to think of it as a mere recreational activity.

And now that we have hormone treatment and trans surgery, we can imagine that we are able to change our genders – indeed, the very concept of gender separated from biological sex requires such a technological context to be in place.

CWR: The term “sexual orientation” is now a common part of modern parlance. But what does it really mean? Or does it mean anything at all?

Trueman: It is a deliberately vague term (though so common that it is hard to avoid) that reinforces the idea that we are defined in a significant way by the direction of our sexual desire without explicitly reducing the person to their sexual desire. It also removes any moral connotations from such. The older language of, say, perversion, carried very strong connotations of being morally pejorative.

It also seems to me that it presses us to thinking of sex in ways that fail to do justice to the fact that sexual desire is intersubjective: it is supposed to exist as desire for another, specific person, another subject. The language of orientation, lacking this notion, tilts toward thinking of sexual desire as focused on general objects (men, women) rather than subject (this man, this woman). And that carries with it a whole philosophy of sexual desire as focused on the satisfaction of the one desiring rather than on the one desired.

CWR: In general, how are “freedom” and “liberty” understood in 2022 as compared to, say, the 1950s or the 1770s?

Trueman: When Thomas Jefferson declared that it made no difference to him how many gods his neighbor believed in because it neither picked his pocket nor broke his leg, he was assuming a notion of freedom that focused on the right to physical safety and the right to own property. His notion of selfhood saw oppression as constituted by a denial or privation of those things.

Today, we operate with a notion of the self that places far more emphasis on our psychological states: Do we feel happy? That rather broadens the notion of oppression to the point where, yes, our neighbors’ beliefs might harm us because they might imply that we are wrong about something. Freedom is now increasingly the freedom not to be offended – something that renders old freedoms (of speech and of religion) far more controversial.

CWR: You point to natural law and theology of the body as two means (among others) of responding to the amoral/immoral fluidity of the current cultural landscape. How can these inform an ecumenical response by Catholics and Evangelicals? And what is the state of Evangelicalism in the U.S. when it comes to addressing transgenderism, expressive individualism, and related challenges?

Trueman: Protestantism’s abandonment of its own natural law tradition in the nineteenth and twentieth century was a disaster. We really are at this moment very dependent upon (and in my case, grateful for) the rich heritage of ethical thought fostered by the Roman Catholic Church.

I see some very hopeful signs. There are Protestants who beginning to think seriously about natural law and the theology of the body but we have a long way to go. Ecumenically, I am encouraged by, for example, the Ethics and Public Policy Center in DC, where I happen to be a Fellow, that provides a great context for thinking through these issues in an ecumenical context.

CWR: Finally, how would you evaluate where we are right now when it comes to what I call “the tyranny of trans”?

Trueman: I see some signs of hope. People seem to have been galvanized by the Lia Thomas issue and the apparent evidence that trans ideology is being used in schools to confuse children and subvert parental authority. I hope that we are witnessing the beginning of significant resistance to this lunacy.

Nevertheless, the trans lobby currently enjoys support from powerful politicians and from the medical establishment. Those are formidable enemies. And it is also certain that, even if the reaction is successful, countless young people’s lives will already have been destroyed by hormone treatment and genital mutilation.

Our age will go down in history as one marked by the most barbaric moral delinquency of adults, whose role should be to protect vulnerable children, not inculcate and then indulge their destructive delusions.

Carl R. Trueman is a fellow in EPPC’s Evangelicals in Civic Life Program, where his work focuses on helping civic leaders and policy makers better understand the deep roots of our current cultural malaise. In addition to his scholarship on the intellectual foundations of expressive individualism and the sexual revolution, Trueman is also interested in the origins, rise, and current use of critical theory by progressives. He serves as a professor at Grove City College.