Published June 21, 2019

National Affairs - Summer 2019 issue

We Americans are fascinated by murder. It leads every local newscast; it fills hour after hour of television entertainment and packs them in at the movies. It has been the subject of novels and plays by important writers — a way into understanding our national temperament and state of mind.

Where does this fascination come from? Ours is essentially a middle-class country, and Hegel and Rousseau wrote that the bourgeois is defined by his fear of death, especially violent death. We have grown accustomed to living peaceable and comfortable lives. And as the world remains a dangerous place, we naturally fear losing our peace, our comfort, and our lives.

The nature of the danger — the direction from which unexpected death comes — has changed over time, or at least the work of some of our best writers suggests it has. That change has affected how we think and feel about chance, fate, desire, individual responsibility, and the general condition of our civilization. It would appear our vulnerabilities as a people are laid most bare in the tales we tell about murder, and the evolution of our best-drawn fictional murderers may have much to tell us about the direction in which American life is headed.

MIDDLING MURDER

The most famous murder in American literature is that of the titular hero in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, published in 1925. Jay Gatsby is shot to death in the swimming pool of his mansion by George Wilson, a gas-station owner who believes Gatsby to be the hit-and-run driver who killed his wife, Myrtle. Although it was Gatsby’s car that struck Myrtle, the driver responsible for the accident is Daisy Buchanan, the woman Gatsby had loved and lost and devoted his life to finding again and winning once more. Gatsby loves her enough that, as he tells the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, he would willingly take the fall for her. Adulterous love is never a clean business, but it isn’t much of a home that Gatsby is bent on wrecking: Myrtle Wilson happened to be the mistress of Daisy’s husband, Tom, who was doing a little slumming.

Daisy and Gatsby had been driving back to Long Island after a tense confrontation in New York City, where she had told her husband she was leaving him for Gatsby, and Tom Buchanan had fired back not only that her best beloved had made his fortune as a bootlegger — Prohibition was in force — but also that, according to a common associate, he was currently involved in far more nefarious criminality. Rumors were rife about the past of the mysterious rags-to-riches millionaire who threw such fabulous parties, and Nick had heard the scuttlebutt that Gatsby had murdered someone.

When Tom openly accused Gatsby of evildoing, which terrified Daisy, Nick looked over at Gatsby and “was startled at his expression. He looked — and this is said in all contempt for the babbled slander of his garden — as if he had ‘killed a man.’ For a moment the set of his face could be described in just that fantastic way.” Perhaps Gatsby was a killer, or perhaps he was just thinking at the moment how much he would like to kill Tom. In any event, there was moral and emotional turmoil enough to spatter all concerned with flying muck; yet Nick concludes that Gatsby was better than the rest of the lot — a corrupt man with an incorruptible dream.

The Buchanans have none of Gatsby’s redeeming purity. When George Wilson, gun in hand, comes after Tom, looking to find out who owns the car that hit Myrtle, Tom, afraid for his own life, directs him to Gatsby. Daisy for her part evidently never tells her husband that it had been she behind the wheel. “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy — they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made….” (Fitzgerald’s ellipsis).

The murderer, Wilson, is almost a non-entity — pitiable, hapless, a born loser, a poor sap. His suicide barely registers as a human loss. The murder owes its gravity to the destruction of Gatsby’s shining hopefulness — ”a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again” — which stands out in relief against his own seamy climb to fortune and the appalling moral slatternliness of the surrounding cast, including the woman of his rich fantasy, the beauty whose voice rings in Gatsby’s ear with “the sound of money.” Yet Gatsby’s death is perhaps as ludicrous as it is tragic — the grotesque result of accident and rash assumptions, the amoral universe showing its teeth in a death’s head grin. The Great Gatsby is America’s favorite romantic novel. What often gets overlooked is the bleak sardonic perfection of its machinery for Gatsby’s annihilation.

Theodore Dreiser published An American Tragedy the same year Gatsby appeared. Like Gatsby, Clyde Griffiths is a young man from the Midwest who comes East in the hope of grasping his main chance. Clyde wants the same things Gatsby wants — money, distinction, the love of a beautiful and wealthy young woman — but he has none of Gatsby’s entrancing pure-heartedness.

Clyde’s good fortune, and ultimate misfortune, is that he has a rich uncle who owns a collar and shirt factory in upstate New York. Clyde heads to the mill town of Lycurgus to claim his share of the American dream: “To think that he should be a full cousin to this wealthy and influential family! This enormous factory!…And he had been thrilled in spite of himself. For somehow the high red walls of the building suggested energy and very material success, a type of success that was almost without flaw, as he saw it.” Dreiser understands the great compulsions, often coarse, sometimes brutal, that propel the national engine; Clyde’s hopes and desires will be of a very material sort.

His ambition has a sharp erotic edge that cuts him deeply with the fear that his desire is unattainable. His wealthy cousins’ friend Sondra Finchley, the daughter of another local manufacturing potentate, is everything he could want in a young woman: “[A]s smart and vain and sweet a girl as Clyde had ever laid his eyes upon — so different to any he had ever known and so superior….Indeed her effect on him was electric — thrilling — arousing in him a curiously stinging sense of what it is to want and not to have — to wish to win and yet to feel, almost agonizingly, that he was destined not even to win a glance from her. It tortured and flustered him.”

Believing he will never stand a chance with Sondra, Clyde turns his attention to the factory hand Roberta Alden, who is susceptible to “the very virus of ambition and unrest that afflicted him.” She is the sort of girl who thinks she is moving up in the world by consorting with the owner’s nephew, her assembly-line foreman. When Roberta tells Clyde she loves him, he thinks he has everything he could ever want: “It seemed at the moment as though life had given him all — all — that he could possibly ask of it.”

But then Sondra takes a fancy to Clyde, and things get complicated fast. Sondra falls hard for him, in her kittenish way, and they plan their marriage; although her parents might disapprove, she will be 18 soon and free to marry without their permission, and in any case her family will surely come around to accepting her husband. “And then would he not be the equal, if not the superior, of Gilbert Griffiths himself and all those others who originally had ignored him here — joint heir with Stuart to all the Finchley means. And with Sondra as the central or crowning jewel to so much sudden and such Aladdin-like splendor.” But Roberta, who is pregnant and has her suspicions about Sondra, expects Clyde to marry her.

And so the young man’s fancy turns to murder: Clyde begins to think ever more seriously about taking Roberta, who cannot swim, out boating on a lake and drowning her. He is not without a conscience, and Dreiser portrays the psychic struggle between fundamental decency and runaway ambitious need: Clyde must decide whether he will pursue creamy sexuality at the social pinnacle to the point of killing for it or settle for the second-rate. Dreiser sees deep inside the mind of the embryonic criminal who cannot help turning over and over again the reasons for and against murdering the woman he so recently loved. Clyde even calculates how much money he will have to spend to pull off his deadly scheme.

He rents a boat under an assumed name, rows Roberta out to a secluded cove, and just when the time is right to dispose of his burden, paralysis seizes him: “And Clyde, as instantly sensing the profoundness of his own failure, his own cowardice or inadequateness for such an occasion, as instantly yielding to a tide of submerged hate, not only for himself, but Roberta — her power — or that of life to restrain him in this way.” Seeing the distress on his face, Roberta comes clumsily toward him, and their accidental collision capsizes the boat. As Clyde watches Roberta struggle in the water and beg for help, he cannot but consider his good fortune; he cannot let this unexpected opportunity go to waste. He lets Roberta drown. “And the thought that, after all, he had not really killed her. No, no. Thank God for that. He had not. And yet (stepping up on the near-by bank and shaking the water from his clothes) had he?”

The law eventually catches up with Clyde and decides that he had, despite his flailing efforts to deny any trace of evil intent. In the face of everyone else’s certainty that he is guilty of murder, to justify himself he wriggles every which way like a worm on the hook:

[H]e had a feeling in his heart that he was not as guilty as they all seemed to think. After all they had not been tortured as he had by Roberta with her determination that he marry her and thus ruin his whole life. They had not burned with that unquenchable passion for the Sondra of his beautiful dream as he had. They had not been harassed, tortured, mocked by the ill-fate of his early life and training, forced to sing and pray on the streets as he had in such a degrading way, when his whole heart and soul cried out for better things. How could they judge him, these people, all or any one of them, even his own mother, when they did not know what his own mental, physical, and spiritual suffering had been?

His mother, a holy-rolling urban missionary, could not possibly see him as he sees himself. “She would never understand his craving for ease and luxury, for beauty, for love — his particular kind of love that went with show, pleasure, wealth, position, his eager and immutable aspirations and desires.”

In his last days on death row, however, Clyde comes around to embracing salvation through Jesus Christ, though Dreiser examines with his customary psychological thoroughness the quaking uncertainty of the condemned man’s conversion. As Clyde shuffles his way to the electric chair, salvation hardly seems a sure thing. “He was being pushed toward that — into that — on — on — through the door which was now open — to receive him — but which was as quickly closed again on all the earthly life he had ever known.”

The earthly life is all anyone really knows in Dreiser’s world, which is the world as most of us know it, and he has drawn a man driven by the longing for the choicest worldly amenities — and willing to kill for them. Clyde Griffiths’s soul, if he can be said to have one, comprises three parts Machiavelli to one part Thousand and One Nights: Straight from The Prince comes “the natural and ordinary…desire to acquire” — the craving to win the world’s prizes, wealth, station, bombshell heiress — by whatever means are necessary, while the fantasy of the poor boy magically granted his every wish steps right out of the story of Aladdin and his lamp. Obdurate reality eventually flushes Aladdin out of Clyde’s system and leaves him with Machiavelli. This is the moral arctic of the modern world.

What then makes this tragedy peculiarly American? Primarily it is the mediocrity of the convicted murderer’s mind and character. There is nothing to Clyde that suggests he might be cut out for a role of honor and renown. He is a very ordinary young man with very ordinary desires: He wants to rise in the world as easily as possible, and has no aspirations higher than securing a place among the wealthy in a provincial mill town; it is the most elegant and charming society he knows, and he lacks the imagination to conceive of anything finer.

Beside a Julien Sorel, the hero of Stendhal’s 1830 novel, The Red and the Black, Clyde seems a figure of small consequence. A carpenter’s son from the provinces, his ambition nourished by dreams of Napoleonic glory, Julien is a young man of intellect, energy, wit, and daring, who makes his way in the world by talent and brass, and wins the heart of a noble Parisian beauty, Mathilde de la Mole, who is unimpressed by an abundance of aristocratic suitors. When a woman from his past, Madame de Rênal, tries to prevent his marriage to Mathilde, he shoots the interloper as she prays at Mass. Although he only wounds her, he is convicted of murder. During his final days, he realizes that Madame de Rênal is his true love, and knows the happiest time of his life in her company as he awaits the guillotine.

Stendhal may stand head and shoulders above, but An American Tragedy is nevertheless a great novel, and the greatest American novel of murder. Although Dreiser is the most barbarous stylist among writers of distinction — his diction ungainly, his syntax garbled — he wins critical regard by his moral seriousness and psychological penetration. His characters live; their lives matter. And if Clyde Griffiths cannot rival Julien Sorel in sheer voltage, that inadequacy is part of Dreiser’s intention: The destructive social and erotic fevers of ordinary American lives constitute a subject as important as the thrilling careers of dashing young French heroes who wish they were Napoleon.

OLD-SCHOOL KILLING

When it comes to murder, Fitzgerald and Dreiser are the most eminent American writers of the old school, in which men kill for familiar, time-honored reasons: the blind rage of vengeance, the seductive gleam of ambition. This conventional sort of murder has an honored tradition in American literature, and its lesser masters include Dashiell Hammett, James Cain, Raymond Chandler, all of whom were considered purveyors of pulp fiction in their day but whose work has now been enshrined in the Library of America. Murder is their special subject, and their principal traffic runs to crimes of limitless avarice and uncontrollable sexual passion.

The most famous novel of this lot is probably Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1930), its celebrity greatly enhanced by the film version directed by John Huston and starring Humphrey Bogart as the San Francisco private eye Sam Spade. The eponymous bird is a foot-high golden statue encrusted with precious jewels, a gift from the chivalric Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem to their benefactor Emperor Charles V in the 16th century. The object has changed hands many times over the centuries, and for years its splendor has been concealed under a coat of black paint or enamel. One owner who was aware of its immense value was murdered in Paris and the statue stolen, and for the 17 years since then, Casper Gutman, “the fat man,” has been chasing it down, with cohorts who are really murderous competitors also in pursuit. In Hammett’s world of perpetual moral gloom, where the strong take what they can and the weak yield or go to the wall, ownership is a matter of cunning and main force.

The moral of Hammett’s story is clear and simple: Murder will out, and murder will beget murder. As the novel ends, Spade hears that Gutman has been shot and killed by his sometime bodyguard. “Spade nodded. ‘He ought to have expected that,’ he said.”

Where Hammett writes of lethal greed, James Cain writes of blood-soaked lust. In The Postman Always Rings Twice, published in 1934, the drifter Frank Chambers, who tells the tale, finds a job at the California hotel, diner, and gas station owned by Nick Papadakis. Events move quickly. On page six, when Nick’s wife, Cora, serves Frank supper, the more potent appetite drives out the lesser: “Her dress fell open for a second, so I could see her leg. When she gave me the potatoes, I couldn’t eat.” What he does eat, he can’t keep down. Serious vomiting tells him this is something like love, if not exactly that: “I wanted that woman so bad I couldn’t even keep anything on my stomach.” Three pages later, their inevitable coupling is sudden and savage.

It becomes clear in a hurry that Nick is going to have to die. On page 15, Nick falls in the bathtub and cracks his skull when the lovers put the lights out and Cora wallops her husband with a homemade blackjack, but the resilient Greek survives the supposed accident. The perfect victim never suspects any foul play. Twenty pages later, when the three of them are out for a ride in the car, Frank brains Nick with a wrench, the lovers send the car plunging down a ravine with Nick’s body in it, and then, before they arrange some convincing injuries for themselves, they have at it with all their might. There is nothing for the libido like a murder jointly executed: “Hell could have opened for me then, and it wouldn’t have made any difference. I had to have her, if I hung for it. I had her.”

The authorities have their suspicions and press to nail the pair. A defense lawyer calls theirs “a perfect murder,” though its perfection is complicated by a $10,000 accident policy Nick had on his life, which Cora claims she did not know about. Legal prestidigitation of genius settles everything in the couple’s favor. They have money now, and they have each other. Their foremost desire is to put the murder as far behind them as possible and live out a middle-class fairytale. Cora gets pregnant, they marry, and a new life opens before them. But then she feels sick after an ocean swim, and as Frank is rushing her to the hospital, he crashes the car into a culvert wall, and Cora is killed.

The district attorney who failed to convict them the first time now argues that they did kill the Greek for the insurance money and that Frank then murdered Cora so he could have it all to himself. Acquitted when he was guilty, he is convicted when he is innocent. “The jury was out five minutes. The judge said he would give me exactly the same consideration he would show any other mad dog.” Legal justice succeeds only inadvertently, and metaphysical justice may be slow and might seem imperfect, but that merely enhances its ironic cunning, which punishes the murderers just when they believe they are home free and will live henceforth as happy, respectable people. The brutal account ends on a note of high sentiment: “Here they come. Father McConnell says prayers help. If you’ve got this far, send up one for me, and Cora, and make it that we’re together, wherever it is.” But it doesn’t seem likely that true lovers’ heaven is in the cards for them.

UNDERSTANDING SUPERMEN

Postman is very much an old-school story, but an encounter that Frank Chambers has with a fellow death-row inmate points to the new wave forming in American murder:

There’s a guy in No. 7 that murdered his brother, and says he didn’t really do it, his subconscious did it. I asked him what that meant, and he says you got two selves, one that you know about and the other that you don’t know about, because it’s subconscious. It shook me up. Did I really do it, and not know it? God Almighty, I can’t believe that! I didn’t do it. I loved her so, then, I tell you, that I would have died for her! To hell with the subconscious. I don’t believe it. It’s just a lot of hooey, that this guy thought up so he could fool the judge. You know what you’re doing, and you do it.

It used to be as simple as that last sentence would have it. But psychopathology soon became the key element in the fictional annals of murder, and the psychopath, the sociopath, and the uncontrollable psychotic would stalk the imaginations of readers, moviegoers, and watchers of television crime dramas for decades to come. Questions of guilt, innocence, and responsibility would prove ever more vexed.

Patricia Highsmith’s distinguished literary career rests on the pathological case. Though she is best known for her Tom Ripley novels, which feature an elegant and attractive sociopath who kills for the sake of the finer things in life, her masterpiece is Strangers on a Train (1950), in which death holds no terror but rather has an irresistible fascination for Charles Anthony Bruno, a wealthy idler and certifiable madman who wants to do everything possible before he dies. High on his bucket list is the perfect murder. He meets the young architect Guy Haines on a train and proposes a scheme of insane audacity: Bruno will murder Guy’s loathsome wife, Miriam, who is pregnant with another man’s child and has no intention of granting Guy a divorce, and to return the favor Guy will murder Bruno’s hated father. A late-night phone call seals the deal, in Bruno’s mind anyway; when Guy hears Miriam is dead he wonders whether Bruno could really be crazy enough to have made good on his proposal. In due course, Bruno tells Guy that he did it, and that he expects Guy to do the honorable thing and reciprocate. When Guy threatens to turn Bruno in to the police, Bruno retorts that he would pin the murder on Guy — what reason, after all, could Bruno have to kill a woman he didn’t know?

Bruno turns up the pressure, sending Guy the floor plan of his father’s house, procedural instructions, and a pistol to kill the old man. Bruno terrifies Guy, who fears what Anne Faulkner, the woman he loves and wants to marry, would think of him if she knew what he has been hiding from her. “If he told Anne the story, wouldn’t she consider he had been partially guilty? Marry him? How could she? What sort of beast was he that he could sit in a room where a bottom drawer held plans for a murder and the gun to do it with?” This respectable ordinary man is plunged into the depths by the actions of a consummately manipulative psychopath. Bruno stalks Guy, and the prolonged tension breaks Guy’s resistance. Respectable ordinary men too can be driven to kill, in order to protect their respectability. One night, Guy goes out and commits the necessary murder.

Guy cannot stop thinking of what he has done, and eventually the murder runs together in his mind with his masterly accomplishment as an architect, in the seductive dance of Nietzschean amor fati. “It was a kind of arrogance, perhaps, to believe so in one’s destiny. But, on the other hand, who could be more genuinely humble than one who felt compelled to obey the laws of his own fate? The murder that had seemed an outrageous departure, a sin against himself, he believed now might have been a part of his destiny, too. It was impossible to think otherwise.”

The hell-bent egotism of this line of thinking is its own form of psychopathology: the mania of the controlling idea. An excess of Nietzsche in the brain has rocketed a good many unfortunates into this sort of madness. As Bruno is out sailing with Guy, Anne, and their friends, in his self-infatuation, his demented pride in engineering the perfect murders, he invokes Nietzsche’s most famous coinage:

“Sure I’m mad!” Bruno shouted to Helen, who was inching away from him on the seat. “Mad enough to take on the whole world and whip it! Any man doesn’t think I whipped it, I’ll settle with him privately!” He laughed, and the laugh, he saw, only bewildered the blurred, stupid faces around him, tricked them into laughing with him. “Monkeys!” he threw at them cheerfully.

“Who is he?” Bob whispered to Guy.

“Guy and I are supermen!” Bruno said.

Things end badly for the supermen. Moments after his ebullient profession of faith, Bruno falls or jumps into the water and drowns. Guy for his part delivers a Dostoevskian confession to Miriam’s former lover, who is too drunk and stupid to care; and the investigator who has been tailing Guy hears the whole story from just outside the door. This too his fate has decreed. Guy’s surrender to the law “was inevitable and ordained, like the turning of the earth, and there was no sophistry by which he could free himself from it.”

The most notorious of murderous American supermen are Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, real-life University of Chicago undergraduates who murdered their neighbor, 14-year-old Robert Franks, in 1924 in order to prove their superiority to what Nietzsche called “slave morality.” The two were obsessed with the philosopher, and the sheer pleasure of taking a life, which for them is an intellectual thrill as much as a visceral one, provides their raison d’être.

Meyer Levin was a contemporary of the killers at the university, and covered the murder for the Chicago Daily News; his 1956 novel Compulsion retails this abomination committed in the thrall of an idea, and the response of law and public opinion to its enormity. The narrator, Sid Silver, is Levin’s alter ego, who considers the crime from the vantage of 30 years of experience, which includes having fought in a war against “an entire nation [that]…seriously subscribe[d] to the superman code.”

The fictionalized murderers, Judd Steiner and Artie Straus, sons of Jewish millionaires and sometime lovers, take satanic pride in their exceptional intelligence, and the liberation from convention that their mental daring permits them. As in Highsmith’s work, and in other novels and plays in the new tradition, the murderers in their lustrous blackness of soul stand out against the civilized proprieties. The unsolved rape and murder of another Jewish millionaire’s son, Paulie Kessler, terrorizes the city, and the new fear abroad is not only of savage animals on the loose but of an unexampled pathology, a rogue bacillus that will ravage humanity:

The child’s fear of wolves prowling in the forest, wolves that will eat you up — even when the child lives in a city where there are no forests, even though he has been told that really there are no such wolves anywhere around him — this childhood fear seemed now to have leaped awake in every soul in Chicago, and the wolves were the primordial menace, some unknown beast, more savage than any beast ever encountered by man. There was a growing anxiety, a growing presage that something new and terrible and uncontrollable, some new murder-germ, was here involved.

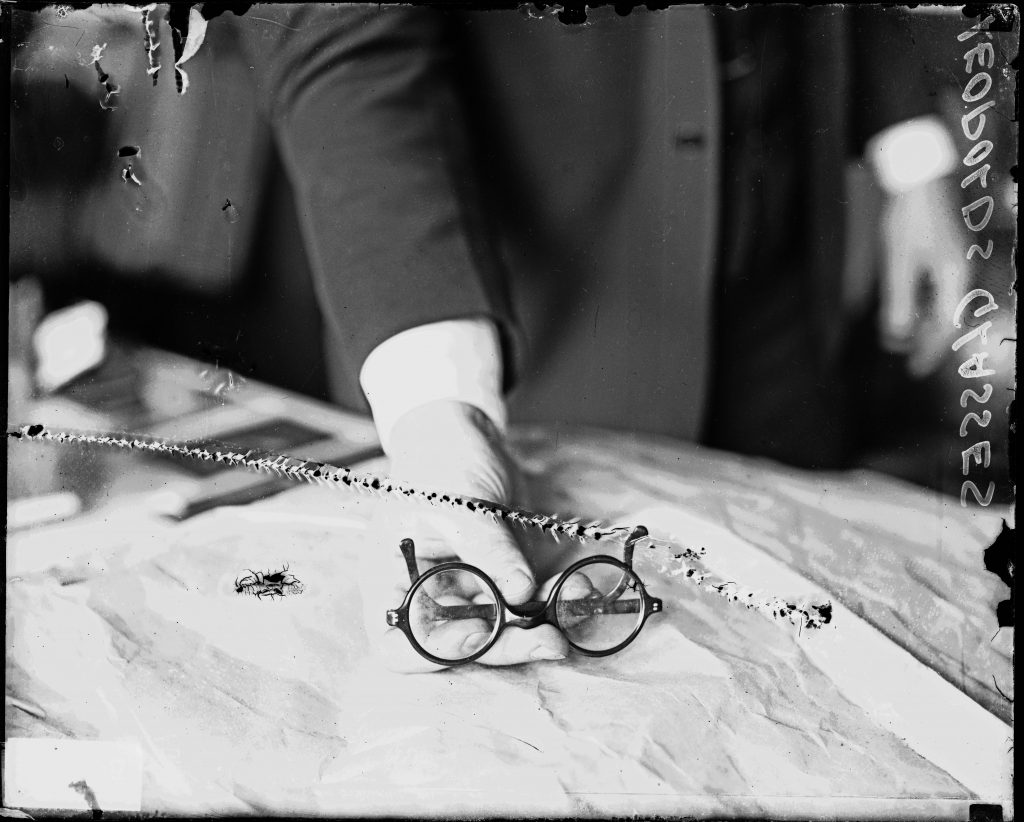

A very different fear torments Judd Steiner after the murder: that at bottom he might be ordinary, that he might want to love and marry an unexceptional girl, that he might really desire a normal life; this fear gnaws at the moral superiority that entitles him to kill with impunity. “But if he can be ordinary…He shudders in horror and fear, as of losing his very self, and at the same time he experiences a frightful sense of something wasted, the murder as a false and wasted act. He has to make an effort to confirm the murder experience as part of his own being” (Levin’s ellipsis). The authorities are able to track down the murderers because Judd lost his glasses when they dumped the body, and this haplessness only confirms his feeling that he is unworthy of so exalted a calling. He supposes himself inferior to Artie, who perhaps had killed before: “[T]he ones Artie had made dark hints about — the campus fellow who had been found shot, the taxi driver found castrated. Artie was driven by some demonic force, and in himself it was not the same. Had everything, then, been a gargantuan mistake?”

The young men’s fantasy of Nietzschean nobility is further undermined by psychiatrists testifying for the defense. The compassionate Dr. Allwin speaks of the murderers not as perps but as patients, each “‘suffering from a functional disorder. Artie’s could develop into dementia praecox, a splitting of the personality, and Judd’s is in the direction of paranoia.'” Two other experts dismiss Judd’s philosophy as “a mere camouflage, a mumbo jumbo of hedonism, Nietzschean aphorisms, Machiavellian slogans, just a smattering of things Judd had read….These were the philosophies of ‘I want what I want.’ They all stemmed from the pleasure principle of the infant. Like his tests, they proved that Judd was emotionally a child.”

Thus Freud displaces Nietzsche as the virtuoso of psychological and moral insight. In the eyes of these learned doctors, the murderers’ most revered authority is a grandiose charlatan.

As one might expect of a University of Chicago murder, the case provokes weighty questions about human nature. The defense attorney, Jonathan Wilk (modeled after Clarence Darrow, who handled the Leopold and Loeb defense), asks whether “‘the mental condition‘” of his clients might not mitigate their responsibility. “And as he spoke, the courtroom was being gradually drawn back from the definition of a word to deeper questions. What was free choice of action? What was free will? And, unsaid, one could hear Wilk’s lifelong rumination, his gentle pessimism, his insistence on some form of mechanistic determinism, his claim that there was no free will.” Wilk makes the “‘two unfortunate lads'” out to be the real sufferers here — victims of a cruel or indifferent Nature, who were driven to murder by an inborn compulsion that science is only beginning to understand. “‘I am pleading for life, understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all.'” Tout comprendre, c’est tout pardoner — compassion, all-comprehending or uncomprehending, has its day: The killers get life in prison rather than the death penalty.

MONSTROUS FATE

What are the limits of compassion for murderers profoundly damaged by nature or nurture or both? Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and its Consequences (1965), which treats the 1959 killing of a wholesome and happy Kansas farm family by a pair of ex-cons, tests those limits. In what has been called his “non-fiction novel,” Capote depicts two Americas at fatal odds with each other: the placid, content, ordinary heartland life at the mercy of viciousness honed in prison and dreaming of making a killing. The killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, had heard that Herbert Clutter had a safe packed with thousands in cash, and they thought it would be an easy score. In the end, they wind up murdering four people for less than $50.

Dick recruits Perry for his native talent, not to say genius. “Several murderers, or men who boasted of murder or their willingness to commit it, circulated inside Lansing [the Kansas State Penitentiary]; but Dick became convinced that Perry was that rarity, ‘a natural killer’ — absolutely sane, but conscienceless, and capable of dealing, with or without motive, the coldest-blooded deathblows. It was Dick’s theory that such a gift could, under his supervision, be profitably exploited.”

The gift appears to be transmitted in the blood, Perry reckons:

When Perry said, “I think there must be something wrong with us,” he was making an admission he “hated to make.” After all, it was “painful” to imagine that one might be “not just right” — particularly if whatever was wrong was not your own fault but “maybe a thing you were born with.” Look at his family! Look at what happened there! His mother, an alcoholic, had strangled to death on her own vomit. Of her children, two sons and two daughters, only the younger girl, Barbara, had entered ordinary life, married, begun raising a family. Fern, the other daughter, jumped out of a window of a San Francisco hotel….And then there was Jimmy, the older boy — Jimmy, who had one day driven his wife to suicide and killed himself the next.

It is sometimes said that psychopaths are born and sociopaths are made; whatever his pathology, Perry seems both born and made for a monstrous fate.

Dick for his part is insulted that Perry speaks of “‘something wrong with us,'” for he proudly considers himself a regular guy: “‘Deal me out, baby. I’m a normal.'” His capacious understanding of normality includes a taste for pubescent girls — he is sufficiently normal to be ashamed of this unseemly proclivity — and a hankering for ultraviolence: “‘I promise you, honey, we’ll blast hair all over them walls.'” A psychiatrist testifying in his behalf cannot say all he wants to say in court: The M’Naghten Rule confines him to the question of whether the killer knew right from wrong, which he did. In a passage almost two pages long, Capote quotes what the doctor would have said had he been given the chance: “‘In summary, he shows fairly typical characteristics of what would psychiatrically be called a severe character disorder. It is important that steps be taken to rule out the possibility of organic brain damage [resulting from a serious head injury], since, if present, it might have substantially influenced his behavior during the past several years and at the time of the crime.'” The law has no use for such mitigating fancy talk, and it comes down hard. Both murderers hang.

Capote’s sympathy for the killers is evident — it is hard to imagine their wretched lives producing anything but misery for anyone — yet in the end he commiserates more passionately with the murdered Clutter family and the townspeople of Holcomb whose comfortable, handsomely ordered world was disfigured. The book’s closing scene shows Al Dewey, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation agent who helped solve the crime, running into Susan Kidwell, who had been the teenaged Nancy Clutter’s closest friend, at the gravesite of the murdered family. Terrible memories darken their amiable chat — ”‘Suddenly, when I’m very happy, I think of all the plans we made'” — but the beauty of ordinary life well lived shines through. “‘Good luck,’ he called after her as she disappeared down the path, a pretty girl in a hurry, her smooth hair swinging, shining — just such a young woman as Nancy might have been. Then, starting home, he walked toward the trees, and under them, leaving behind him the big sky, the whisper of wind voices in the wind-bent wheat.”

BORED KILLER

By the 1990s, the native goodness of ordinary American life is nowhere to be found in the American annals of fictional murder. In American Psycho, Bret Easton Ellis creates a murderer so vile that it is impossible to feel compassion for him, even though he is obviously insane and his insanity is the product of American society’s wholesale corruption — a civilization so rotted out that fiends like him are inevitable and the wonder is that there aren’t more of them.

A Wall Street financier who has inherited his father’s firm, a graduate of Exeter and Harvard, handsome, athletic, charming, impeccably groomed and dressed, Patrick Bateman lives the life of a man about town for whom every sensual satisfaction is readily available. But a profound psychic disturbance throbs like a terrible wound. His hallucinations can make normal social intercourse something of a trial. Usually his mind is occupied with fantasies, memories, and anticipations of violence, especially sexual violence, which furnish the genuine interest in an existence otherwise devoted to chichi restaurants, the delivery of learned disquisitions on rock-and-roll heroes, and the adornment of his person. Early in the novel he still finds it possible to enjoy normal diversion:

I have a knife with a serrated blade in the pocket of my Valentino jacket and I’m tempted to gut McDermott with it right here in the entranceway, maybe slice his face open, sever his spine; but Price finally waves us in and the temptation to kill McDermott is replaced by this strange anticipation to have a good time, drink some champagne, flirt with a hardbody, find some blow, maybe even dance to some oldies or that new Janet Jackson song I like.

By the end he can’t stop killing. The violations he commits upon women’s bodies are so horrifying one dare not quote from any relevant passage.

But Ellis plainly intends far more than an exercise in the pornography of violence. He is interested not in the banality of evil — Patrick Bateman relishes his malignancy with the gusto of Richard III — but in the evil of banality. Bateman and his crowd represent the worst in the native character: The young and moneyed are shallow, preening, casually racist, classist, and sexist, morally defunct, despising those broken by the capitalist system that allows them to live like lords of the manor. They exemplify every progressive nightmare of white privilege run amok. From this emptiness, monstrosity blossoms.

Ellis’s vision is a generation ahead of its time. Bateman’s particular hero is Donald Trump, who in 1991 was no more than a celebrity plutocrat indulging every sybaritic whim, but who has since acquired a demonic reputation to rival that of Patrick Bateman. No Trump, no Bateman, one might have said in the day, as one would say no Dryden, no Pope; now it’s no Bateman, no Trump. One has to laugh at the author’s inane attempt at profound social critique. Ellis’s is a highly ambitious novel, and a fatuously pretentious one. To derive obsessive perversion and murderousness from obsessive concern with designer labels, fine dining, and the adventures of The Donald pitches Ellis face-first into absurdity.

MURDER WITHOUT MEANING

The American art of murder has traveled a long way from the days of Fitzgerald and Dreiser. Where murderers once killed for some plausible purpose, they now do so for the elemental joy of killing. The dread of violent death coming from nowhere is the great theme of the new wave of murder literature, and there are more distinguished novels and plays in this mode than could fit here: Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story (1958), in which a self-described lunatic bent on committing suicide-by-stranger draws out the fear and latent rage in a peaceable man enjoying a quiet afternoon in Central Park; Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song (1979), in which a man born to raise hell murders two strangers because he is upset his girlfriend left him; James Ellroy’s The Black Dahlia (1987), in which a young woman sliced in half is but an amuse-bouche for an insanely evil serial killer who collects vital organs; David Mamet’s Edmond (1982), with a bored middle-class householder finding his authentic self in a crazed act of butchery.

More recently, it is the psychopath with no conscience and the psychotic directed by demons that terrify us the most. To die for no reason at the hands of a madman has become the pervasive fear. Like the products of popular culture — such as the long-running television hit Criminal Minds, which features a new twisted killer every week — the works of serious writers testify to the condition of the modern American psyche. The enduring popularity of the murder novel shows that, for all the unprecedented comfort and safety of our lives, the fear that our world can suddenly be broken into by a homegrown monster never leaves us. And the changing nature of that monster shows how our own drives and cultural pathologies have changed over the last 100 years. The monsters of previous generations could give intelligible reasons for killing, warped though their reasoning was, or they might have suffered from a medically legitimate disease or defect. Our contemporary monsters appear to be soulless, virtually inhuman, their internal voids to be filled up with violence.

Lincoln famously said any real danger we faced would come from within: “If destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher.” Is emptiness the danger our late republic is too comfortable to see coming?