Published March 2, 2018

Early in the Netflix series called Babylon Berlin, set in Germany in 1929, the police vice squad raids the studio of a pornographic film company. At first, we hear only the off-camera voice of the director speaking to “Mary,” “Joseph,” the “shepherds,” and so on—and, for a second, we infer that it is a rehearsal for a school Christmas pageant.

Then the camera, following the police officers, enters the studio to disclose the pale, naked bodies of actors engaged in an orgy in a manger—coupling in the fashion of barnyard animals, as the director calls out instructions and encouragement.

The scene is not just a travesty of the Nativity but a travesty of blasphemy itself—and, somewhere beyond that, a comment on a style of German transgressiveness so naïve and humorless and boorish and literal-minded (almost moronic) as to be . . . not innocent, exactly, but bovine, a little too dumb to arouse an intelligent person’s indignation. One feels disgust, but it is not directed at the religious transgression; rather, one is overwhelmed by the depressing, over-the-top stupidity of it all, the squalor. The vice squad officers, all business and a little bored, take the scene as a matter of course. These are the polluted waters of their culture. This is their swamp. (Weimar Germany was a prequel, needless to say.)

It’s possible to have a similar reaction to aspects of America in 2018. Jean Cocteau once said, “Stupidity is always amazing, no matter how often one encounters it.”

It’s not that our violence, pornography, stupidity, etc., will necessarily lead on to a twenty-first century version of Hitler; the current disturbances might as easily conjure a twenty-first century version of Stalin, or, more likely, a reign that enlists totalitarian cybernetics, of which we have had glimpses and warnings. It’s just that the violence, pornography, and squalid politics are such an indictment of what we have become, and what we have come to tolerate. Almost everyone, I think, shares the sense that we inhabit an age of travesties; everywhere, there is an atmosphere of travesty. Prodigies of nature itself proclaim it—extreme hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, travesties of weather.

We disagree about which side is responsible for what has gone wrong in our culture and politics. Probably everyone agrees that social media, along with talk radio and cable television, live by the dynamics of travesty and do their part to sustain it.

Mass school shootings make a travesty of the Second Amendment—and of the idea of kids in school, and of childhood itself. The multi-billion-dollar business of pornography—which has expanded to become a signature style of the mass culture, so that explicit sexual scenes are as common as Busby Berkeley production numbers in movies in the thirties—makes a travesty of love, of the First Amendment, and of the sex act itself.

Leading universities have turned themselves into hybrids of Mr. Rogers’ neighborhood and Mao’s Red Guards. They have become madrassas of identity politics, given over to dogmatism, indoctrination, the coddling of grievance, and the encouragement and manipulation of neurotic youthful insecurities for the purpose of consolidating political power. The effects of travesties being committed on American campuses, where the mind of the hard Left is embedded in faculties, administrations, and boards of overseers, will be felt for generations. The damage may be irreparable.

Consider the comedy of the pronouns, which is symptomatic—and hilarious, if you can stand it. In the Alice in Wonderland of academe, pronouns are deemed to be discretionary. A person may choose a unique pronoun (“zhi,” “zher,” or “Gloria Swanson,” or “John Foster Dulles” —up to you, precious: we leave the choice to your iridescent narcissism).

This is a travesty of the sanctity of the person and of individual freedom. It is not social justice but vandalism of the language—self-obsession carried beyond the reach of parody. It is the sort of mischief that children do when they have no parents worthy of the name; universities make a wicked travesty of the idea of in loco parentis.

Shared meaning— language and the community of understanding that it fosters— dissolves under the pressure of ideology. Sex between a man and a woman (an arrangement that accomplished its biological purpose for thousands of years after the moment when Adam and Eve left Eden and entered history) becomes “heteronormative” behavior— the vaguely disreputable or distasteful preference of mere “breeders,” only one of many choices, after all. Meantime, the open-ended LGBTQ sequence expands its differentiated offerings seemingly each week, and stretches on indefinitely, like the numerical value of pi.

Travesty, as a phenomenon of politics and culture, is what happens when exaggeration has no place left to go—except to the last locked door in Bluebeard’s castle. Things are first stretched, then grossly parodied, then done to death. Travesty abhors compromise, scorns moderation, or careful thought; the travestied Left and travestied Right are twins, and converge in the neighborhood of coercion and certitude.

There is a generational dynamic at work in this. Travesty is the way of the twenty-teens, just as it was the style of the 1960s, which was a noisy travesty of a decade. The vast baby boom generation was a travesty of a generation; the boomers were then (roughly) in their adolescence, a stage of life which is itself a travesty of the sane and normal. Now the old age of the boomers recapitulates the drama of their youth— except that the 2018 production has a certain desperate quality.

Are we witnessing the dawn of a new era? Or merely the twilight of people who supposed themselves to be “forever young?” Is it possible that the boomers at long last have lost control of their own story, and have turned it over to forces of travesty that they themselves called forth? In part, I blame a certain historical flippancy in the boomers—their overprotected and overprivileged beginnings, their narcissism, their lack of humility—elements of character that in turn have caused their responses to history to be self-important and hysterical, and have transmitted themselves to their children and grandchildren in deadlier variations.

Travesty seems to progress in the way that addiction does. Travesty is an addiction. And it occurs to me that what we see in both addiction and travesty is a vindication of the Fibonacci Sequence. Fibonacci (1175-1245, approximately) was the Italian mathematician who devised the sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, and so on) in which each number is the sum of the two previous numbers (5 plus 8 gives you 13, for example). It is a design (a prediction) of proliferation, or elaboration. I think it may apply not only in mathematics but in culture.

It’s my theory that the Fibonacci numbers have been at work—by a process of (shall we say) oblivious tumescence—in the elaboration of American life and politics and culture since the 1960s, with alarming accelerations in the last few years. One thing not only leads to another, but leads on to another by a sort of mandate of exaggeration, so that the last two numbers (so to speak) are always added together to produce, not a linear, orderly progression (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and so on) but rather an organic exaggeration advancing, at each step, to exaggeratedly greater exaggerations.

Fibonacci numbers go on forever. But a society cannot go on compounding its travesties indefinitely. We are undoubtedly approaching a crisis in which our travesties—one way or another— will have to resolve themselves, either by committing suicide or burning down the house (which is what travesties and addicts often threaten to do), or by sobering up and going to meetings and learning to behave like serious grownups.

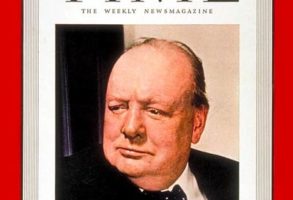

Lance Morrow, the Henry Grunwald Senior Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, was an essayist at Time for many years.