Published September 9, 2020

George Weigel’s weekly column The Catholic Difference

Father Richard John Neuhaus put two Big Ideas into play in American public life. The first was that the pro-life movement (of which Neuhaus was an intellectual leader) was the natural heir to the moral convictions that had animated the classic civil rights movement (in which Neuhaus was also deeply involved). The second was that the First Amendment to the Constitution did not contain two “religions clauses” but one religion clause, in which “no establishment” (i.e., no official, state-sanctioned Church) was intended to serve the “free exercise” of religion. Neither of those Big Ideas is welcome in today’s Democratic Party, in which Neuhaus (then a Lutheran pastor) was once a congressional candidate, and of which he remained a registered member until his death in January 2009.

Those who point out that the 2020 Democratic platform has the most radical pro-abortion plank in American history, and that the same platform promises to hollow out religious freedom in service to lifestyle libertinism, risk being labeled “culture warriors.” Well, so be it. “Culture warrior” is snark masquerading as thought. Facts are facts. And one of the sad facts of this unhappy political moment is that Neuhaus’s effort to rescue the Democratic Party through two Big Ideas was frustrated because those two ideas got linked—and then rejected, thanks to the corruption of rights-talk that preceded, made possible, and was then accelerated by Roe v. Wade and its abortion license.

While Neuhaus’s interpretation of the First Amendment on religion has gained some traction in the federal courts (including, it seems, the Supreme Court), it hasn’t dislodged the alternative view in much of the academic legal establishment or the media. That alternative was baldly stated by Harvard law professor Lawrence Tribe in his constitutional law textbook. In the First Amendment, Tribe wrote, there is a “zone which the free exercise clause carves out of the establishment clause for permissible accommodation of religious interests. This carved-out area might be characterized as the zone of permissible accommodation.”

Ironically, Tribe agrees with Neuhaus on one point: There is one “religion clause” (even though the professor uses the conventional rhetoric of two such clauses). But in Tribe’s view, which has now been replicated in the 2020 Democratic Party platform, there is really just one “religion clause”—that which prohibits the state’s “establishment” of religion. Being tolerant to some degree, good liberals like Professor Tribe will try to find some wiggle room to “accommodate” religious “interests”—much like the liberally tolerant would “accommodate” the “interests” of Flat Earthers. But only up to a point.

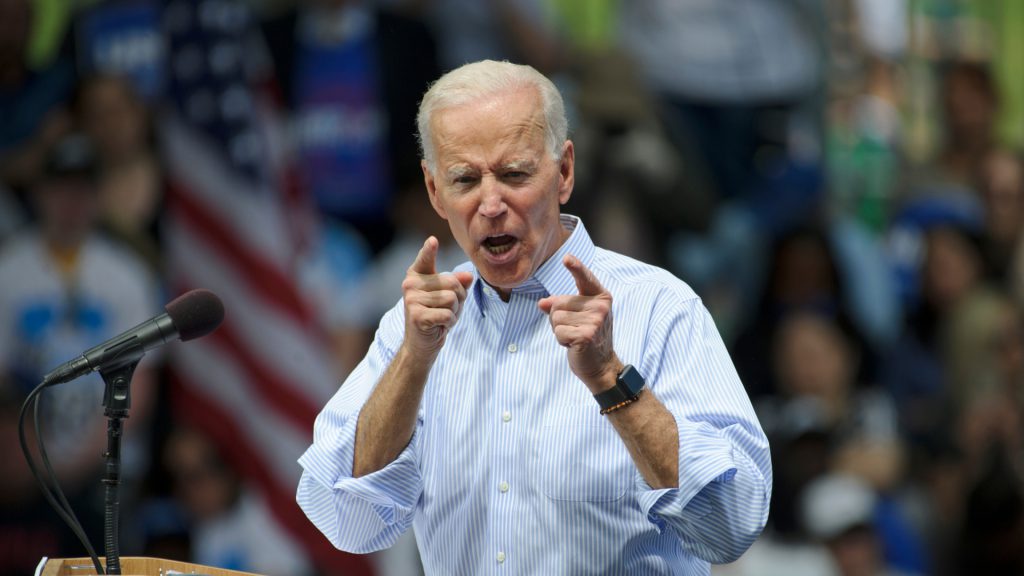

That point was drawn close to the bone by the 2020 Democratic Party platform, which rejects what it called “broad religious exemptions” that “allow businesses, medical practices, social service agencies, and others to discriminate.” What that means in plain English is that, under a Democratic administration allied to Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, the Little Sisters of the Poor will be compelled to provide contraceptives, some of which are abortifacients, to their employees. That, and nothing other than that, is what the Democratic platform promises. That is also the policy the Democratic candidate for president has said he would support. Does anyone doubt that his running mate (who seems to think the Knights of Columbus are a hate group because they espouse the understanding of marriage espoused by Barack Obama in 2008) disagrees?

This is Tribe’s First Amendment theory, turbocharged: The “religious interests” of the Little Sisters of the Poor (and evangelical Protestants, Orthodox Jews, Mormons, and all others who have religiously-informed, conscience-based objections to contraception, abortion, the redefinition of marriage, and the full LGBTQ agenda) do not fit within that “zone of permissible accommodation” that “the free exercise clause carves out of the establishment clause.” So those parties are out of luck—and out of legal protection, unless the Supreme Court comes to their rescue.

In this context, appeals to personal piety, rosary-carrying, and so forth ring hollow, however sincerely felt that piety may be.

It is fatuous to dismiss concerns over the rinsing-out of religious freedom as the overwrought fretting of culture warriors. The commitments in the Democratic platform are plain, and there can be no reasonable doubt that those commitments will be given legislative and regulatory effect by a Democratic administration in league with a Democratically-controlled House of Representatives and a Democratically-controlled Senate. Those are the facts. They are not the only facts to weigh. But those facts should certainly bear on conscientious Catholic voting for all federal offices in 2020.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of Washington, D.C.’s Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he holds the William E. Simon Chair in Catholic Studies.