Published April 6, 2017

I just returned from a three day trip to Rome, where I had the great honor of speaking on the topic of the family at the international conference commemorating the 50th anniversary of Pope Blessed Paul IV’s Popularum Progressio. The conference was convened by the new Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development (merging prior Vatican offices of Justice & Peace, Cor Unum and others).

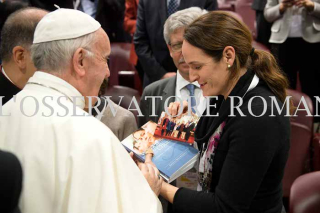

I enjoyed my time there immensely — and, as a speaker, was among the few to receive a personal greeting from the Holy Father. I’ve included a picture below of that blessed encounter (in which I asked him to bless my family and, recalling his request for work articulating a “new theology of women,” gave him a copy each of Women, Sex & the Church: A Case for Catholic Teaching and Promise and Challenge: Catholic Women Reflect on Feminism, Complementarity, and the Church.) The Holy Father addressed the conference, speaking to the need to “integrate” all of the persons of the earth, noting that “the duty of solidarity [] obliges us to seek fair ways of sharing.”

Both Cardinal Turksen, prefect for the new dicastery, and Cardinal Müller, prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, gave truly beautiful introductory remarks. Both began with the anthropological foundations–and transcendent realities–that undergird the Church’s work in the world.

Cardinal Turksen was especially eloquent on the unique God-given nature of the Church’s mission in the world. He spoke first of the person’s communal nature, the centrality of solidarity with the poor, and the Church’s “persevering commitment to the common good.” And then, emphasizing the duties the rich have to the poor, he paraphrased Pope Paul VI’s use of a quote of Saint Ambrose in Popularum Progressio. St. Ambrose: “You are not making a gift of what is yours to the poor man, but you are giving him back what is his. You have been appropriating things that are meant to be for the common use of everyone. The earth belongs to everyone, not to the rich.”

But he then went on to say that each person must be an “artisan” of his or own destiny, since “every man is born to seek self-fulfillment, for every human life is called to some task by God” (PP, 15). He said, importantly, that the development of the self is derived from the transcendent call of God, and so is “incapable of supplying its own meaning.” And thus, he went on to emphasize, now quoting Pope Benedict, that agents of development must be people of prayer. He happily noted that some in the world development community had widened its focus to include more than indices of economic and social transformation in its analysis of development, but that “the Church still contributes something special: prayer.”

More Turksen themes: The transcendent character of the human person is the reason the Church has authority to speak–and must speak–in the world. Without our acknowledgement of God and of the human person’s eternal destiny, development is denied or truncated. The human person may accumulate wealth but does not truly develop. Development is not something done to a person, but is an invitation to answer his vocation, to take responsibility for his own fulfillment. Thus, the principle force in development is the rule of charity: making Christ’s love and invitation real to others.

Cardinal Müller, for his part, spoke of the need to reflect on Gaudium et Spes, the “magna carta” of development, written just before Popularum Progressio, in order to fully understand the nature of the person and his efforts in the world. All the institutions of the Church must always work to reveal God’s love to each person: the origin, essence, and mission of the Church must be understood in light of the incarnation, so that the human person might reach his fullness according to the moral and spiritual nature of man.

The Cardinal differentiated the Catholic approach of development from the many political ideologies especially powerful during the 20th century, but still present in different names or forms today. From the CruxNow article reporting on the conference:

Non-Christian visions of development include the “communist” idea of “creating heaven on earth,” the “utilitarian” idea of seeking “the greatest level of happiness for the most people,” the “Darwinian” or “imperialistic” notion of the survival and thriving of the strongest, and the “capitalistic” vision “with the exploitation of the world and labor.” “If we use these means, we are violating man’s dignity,” Müller said.

Echoing themes from Cardinal Turksen’s remarks, Cardinal Müller reminded the participants that we cannot produce God’s kingdom on our own strength. We need grace: we must ask the help of the Holy Spirit, the “spirit of charity that sanctifies us.” “Even good works are worth nothing if not rooted in the love of God through the Holy Spirit.”

He concluded by talking about new forms of “colonialism” conveyed under the term “modernism” or the “well-being society.” He said these can be a denial of other cultures that are “authentic expressions of the human…Different people can announce the work of God in another language…the single culture is the culture of God.” And finally, we must not forget that each person must be redeemed by overcoming sin within himself. Only this interior struggle against moral evil will allow for the creation of “dignified conditions.”

I could go on, recounting other terrific, eye-opening speeches, offered by cardinals and bishops from around the world, as well as a good number of impressive lay people. But let me turn to my own.

Notably, the section on the family comes right at the heart of Popularum Progressio. Here’s much of it: “The natural family, stable and monogamous, as fashioned by God and sanctified by Christianity, —”in which different generations live together, helping each other to acquire greater wisdom and to harmonize personal rights with other social needs, is the [very] basis of society.” (PP36) Thus, the title of my talk (as given to me) was: “The Family: Between Personal Rights and Social Needs.”

My remarks were self-consciously American, offering a glimpse into our free and prosperous nation, now at risk of “coming apart.”

[A]s we think together about integral human development, I hope to offer some lessons from the United States that might serve as a kind of bell-weather for developing nations, so as not to, in the words of Popularum Progressio, “allow economics to be separated from human realities” (PP, 14). As Pope Paul VI warned: “The developing nations must choose wisely from among the things that are offered to them [by the wealthier nations]. They must test and reject false values that would tarnish a truly human way of life, while accepting noble and useful values in order to develop them in their own distinctive way….” (PP, 41)

I focused especially on “the diametric trajectories of the marrying rich and unmarrying poor,” given the data on outcomes for the children of each, and that this trend was especially foreboding for both income inequality and the flourishing of the most vulnerable. I went on to diagnose the decline of marriage among the poor as being, at least in part, due to the especially harsh effects of the sexual revolution upon poor women:

[W]hat has become increasingly difficult to ignore, even for secular thinkers, is the way in which the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 70s dramatically altered the circumstances in which poor women bear and raise their children. The decoupling of sex from marriage and marriage from childbearing, ushered in by the sexual revolution, unraveled a working-class culture of once stable marital bonds that children need and both mothers and fathers relied upon for their success at home and at work, and in all of life.

I then turned to some new data showing that the most well-educated women in the US are getting and staying married at the highest rates of all demographic groups today.

Whether working outside of the home or exclusively within it, these elite women well understand the unique contributions their husbands make to their children’s well-being and to their own happiness. They well understand that collaboration and “reciprocity” (AL, 54) in their marriages is the surest ticket to their children’s well-being—and to their own.

And then here’s the central part of the talk:

In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis rightly notes that “[h]istory is burdened by the excesses of patriarchal cultures that considered women inferior,” and that were sometimes “marked by authoritarianism and even violence.” But recent history, as experienced by poor single mothers in my country and across the Western world and beyond, does not look kindly upon the radical feminist corrective to the harsh inequities that sometimes accompanied traditional marriage. As Pope Francis suggests, these inequities “should not lead to a disparagement of marriage itself, but rather to the rediscovery of its authentic meaning and its renewal.” (AL, 53), since, Amoris Laetitia again, “violence contradicts the very nature of the conjugal union” (AL, 54).

Ensuring women’s rights within the family and in society requires strong prohibitions against domestic violence and other forms of violence against women and children; legal protections for women in the workplace; just honors and support for the culturally-essential care work that women disproportionately undertake in all societies, including the most egalitarian; and equal access to food, health care, education and, importantly, political participation.

But, in the effort to help families more authentically “harmonize personal rights with social needs,” developing nations with strong family traditions ought not give into the “ideological colonization” that threatens the family from powerful feminist organizations within wealthier nations, especially my own.

Equal rights for women does not require that women suppress their fertility, reject their unborn children, or abandon their hopes for a joy-filled, life-long marriage. The feminist response to the sexual asymmetry between men and women—the fact that women get pregnant and men do not—too often demands that women seek a sort of faux-equality with men, by “imitating models of ‘male domination,’” (EV, 99) as Evangelium Vitae put it, in prioritizing abortion and contraception over women’s educational and broader health care needs. Rather, the far better, and indeed more equitable, just and authentically pro-woman response to sexual asymmetry, is to reconfirm in all cultures the essential and distinctive obligations that fathers have in the family, and to reimagine the dynamic collaboration of men and women in the lives of their children and beyond.

“We often hear” Pope Francis writes, “that ours is ‘a society without fathers…. In our day, [Francis continues] the problem no longer seems to be the overbearing presence of the father so much as his absence, his not being there” (AL, 177). The Holy Father suggests that “some fathers feel they are useless or unnecessary…[and even that] manhood itself seems to be called into question” (AL, 176).

And so, even as we celebrate the progress for women in many countries—and seek to promote it more authentically in still others— we must bring into sharper relief the essential contributions men make as husbands and fathers within the family. Eminent anthropologist Margaret Mead famously said that “the central problem of every society is to define appropriate roles for the men,” as women’s identity has always been caught up in forging life and building relationships, in the home, in the wider community, and now, in a growing number of countries, in the corporate boardroom and the hospital emergency room. With changing roles for women, men are struggling with their identities more than ever; many men are floundering, feeling unneeded, even unwanted, opting out of life through drugs and pornography, or re-asserting their presence through violence and terror.

But men are needed in the family today, as they always have been, by their children—and by their children’s mothers. Studies out of the US show that a father in a loving relationship with the mother of his children is far more likely to have children who are healthier, both psychologically and emotionally. And, as it turns out, the single most important determinant of a mother’s happiness is the very same: the father’s commitment to and emotional investment in the woman’s well-being and in that of their children. In addition, both marriage and fatherhood can have a deeply transformative effect on men themselves: they work harder, advance in their jobs, are less likely to commit crimes, have less substance abuse, better health, and importantly, grow in religiosity. The positive impact upon men of marriage and fatherhood—and in turn, of religious faith—redounds not only to the benefit of their wives and their children, but also to their workplaces, their communities, their nations.

The rest of the talk is dedicated to the transformative power of indissoluble marriage upon both women and men – and, of course, children.

The primary obligation parents have to their children, after the most basic of necessities, is for their parents to truly love, respect, and honor one another….

And thus, we must always affirm that assistance to developing nations does not detract from, but instead promotes the mutual love and collaboration between husband and wife, helping each, as necessary, to recognize the inherent dignity of the other, and teaching them to grow in affection and in trust….

And so, it is we, in the Church, who must prioritize the health and strength of every marriage – for who else in the world right now knows how important each and every marriage is to the development of persons and of nations!? The Holy Father again: “As Christians, we can hardly stop advocating marriage…We would be depriving the world of values that we can and must offer” (AL, 35).

I conclude (to the great satisfaction, I learned, of the many Africans in the room):

As Popularum Progressio rightly notes, “many nations, poorer in economic goods, are quite rich in wisdom and can offer noteworthy advantages to others” (PP, 40). As we come together these days to promote the integral human development of all peoples, let us heed the wisdom of those nations that still enjoy rich family cultures and let us learn from them. It is, after all, the meek and the vulnerable, the cared for and the caregivers within the family, who will inherit the earth.

Erika Bachiochi is a visiting fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.