Published September 11, 2017

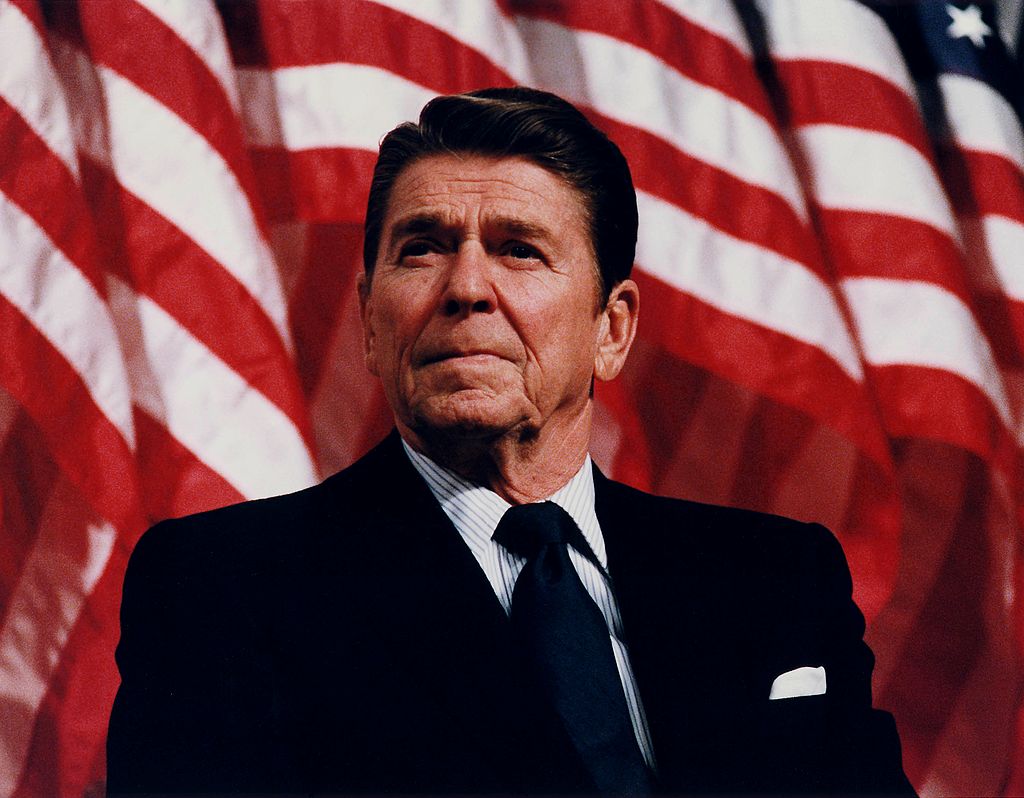

Conservatives revere two things above all else: The Constitution and Ronald Reagan. As we celebrate this Sunday’s 230th anniversary of the Constitution’s signing, self-described constitutional conservatives might want to know what their political idol thought about our founding document. They would find that his thought was more nuanced, and a bit less conservative, than is commonly believed.

Reagan revered the Constitution as much as any conservative. Even during what he called his “hemophiliac liberal” phase, he believed that America was a special country. Contemporaries recall that he studied the Constitution between takes on movie sets in 1941, and he was so taken with his trip to Mount Vernon that year that his then-wife, Jane Wyman, bought him a replica of George Washington’s writing desk as a present.

Indeed, his reverence for America’s dedication to human freedom was in part the cause for his turn to the right. In 1947, he became involved in a fight to prevent suspected communist infiltration in the movie industry. Scales fell from his eyes when a group he belonged to refused to endorse free enterprise and the American Constitution, with at least one famous musician saying he preferred the Soviet Constitution. Reagan remained a liberal and a Democrat for a decade after these incidents, but one can say that his political journey started then as he sought to think through for himself what realizing America’s founding promise through politics really entailed.

Reagan’s conservative turn was accompanied by the development of a consistent philosophy of constitutionalism. He believed that the document’s primary strength was the limitations it set upon government, limitations that ensured government could never remove an individual’s basic democratic rights. Judges, he believed, should interpret laws and the Constitution, not make them. With the able assistance of his longtime aide, lawyer, and eventual attorney general, Edwin Meese, Reagan helped to popularize what is today known as the “originalist” or “original intent” school of constitutional jurisprudence — that the Constitution should be interpreted in light of the intent its drafters held at the time it was drafted.

The challenge with this view comes when applied to the variety of programs and agencies that have been passed and erected in the decades since the New Deal. The powers delegated to Congress in Article 1 do not include the power to establish a tax-financed retirement pension system, for example. Nor does it provide for expert agencies to regulate pollution on a national basis, or provide for grants to states for a variety of purposes that at the time were thought to be exclusively under the states’ purview, such as education or transportation. Many conservative lawyers believe a consistent application of original intent would lead to these programs being struck down as unconstitutional.

Reagan was not a lawyer and did not think about the Constitution in lawyerly terms. In his speeches, his criticisms of judicial overreach always addressed the case where a court overturned a democratically passed law supported by a majority of the people. To my knowledge, he never directly addressed the situation posed above: What should a judge do when faced with a democratically passed law supported by a majority of people?

His speeches do, however, point to an answer: If the people validly consulted and through their elected representatives passed a law, their will should be upheld. Reagan did not echo the claim made by many of his conservative contemporaries, such as Barry Goldwater, that New Deal legislation was unconstitutional because its aims were not authorized by any explicit power granted to Congress. Instead, he criticized what he believed was a permanent government and bureaucracy that was expanding government without popular consent.

In lawyers’ terms, he was advocating the idea that the people are the ultimate arbiters of what disputed constitutional clauses mean through their elections, not the Supreme Court. While this view seems odd today, it was championed in the past by James Madison, Andrew Jackson, and Abraham Lincoln. A court decision may decide a particular application of the Constitution to a case, in this view, but it does not preclude subsequent political action to implement another view of the Constitution’s meaning.

In this, as in so many other things, Reagan proved wiser than his friends. The power of the Constitution comes not from its words but from its ethos. Abandon belief in that, and no mere parchment barrier will preserve the limits its drafters intended to install. Conservatives who wish to restore the Constitution today, then, must rely less on judicial theory and more on political persuasion if they wish to reach their goal. And to do this, they should study the words and deeds of that masterful politician, the Gipper himself.

Henry Olsen is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and the author of The Working Class Republican: Ronald Reagan and the Return of Blue-Collar Conservatism (Broadside Books).