Published June 30, 2017

As Independence Day approaches, Americans are divided. We are conflicted along lines of party, region, education and class — and these divisions have left us with a politics that just feels broken. We all love our country, but we can’t even agree on why and how to love it. Patriotism itself has become a sticking point.

There has long been an argument, roughly along the axis of conservatism and progressivism, about whether to love America for what it has been or what it should be. The right inclines to American exceptionalism, and the sense that our nation’s roots in self-evident moral truths render it a unique force for good in the world and make its politics distinctly elevated. The left inclines to a more redemptive hope in America — the idea that our country has been working from its birth to overcome its unique sins, and that it has made some progress but has much more to make.

Liberals argue that the conservative form of patriotism sanitizes history and descends into jingoism. Conservatives say the left’s form of patriotism isn’t so much a regard for America as for liberal political ideals, which progressives hope our country might increasingly come to resemble.

In our time, President Trump and some of his supporters have brought to the fore another, perhaps even deeper disagreement over patriotism. Trump is not an American exceptionalist. “I don’t like the term, I’ll be honest with you,” he said in 2015. “. . . Look, if I’m a Russian, or I’m a German, or I’m a person we do business with, why, you know, I don’t think it’s a very nice term.” More than not nice, he seems to think it’s not true: What stands out about America, Trump argues, is not its ideals or its gradual self-improvement but the simple fact that it is our country. So America’s leaders should do what the leaders of all other nations do and put their own nation first. “At the bedrock of our politics,” Trump said in his inaugural address, “will be a total allegiance to the United States of America, and through our loyalty to our country, we will rediscover our loyalty to each other.”

These differences among three types of patriots have a lot to tell us about our contemporary politics. But as they are deployed in political debates, they often serve to narrow our sense of the American political tradition. Each camp understands its adversaries as speaking somehow from outside that tradition and perhaps against it. So patriotism itself becomes a source of disunity.

But in fact, these different forms of patriotism all speak from within our tradition. All have deep roots, and the tensions among them might point us toward a better understanding of how our society should regard itself.

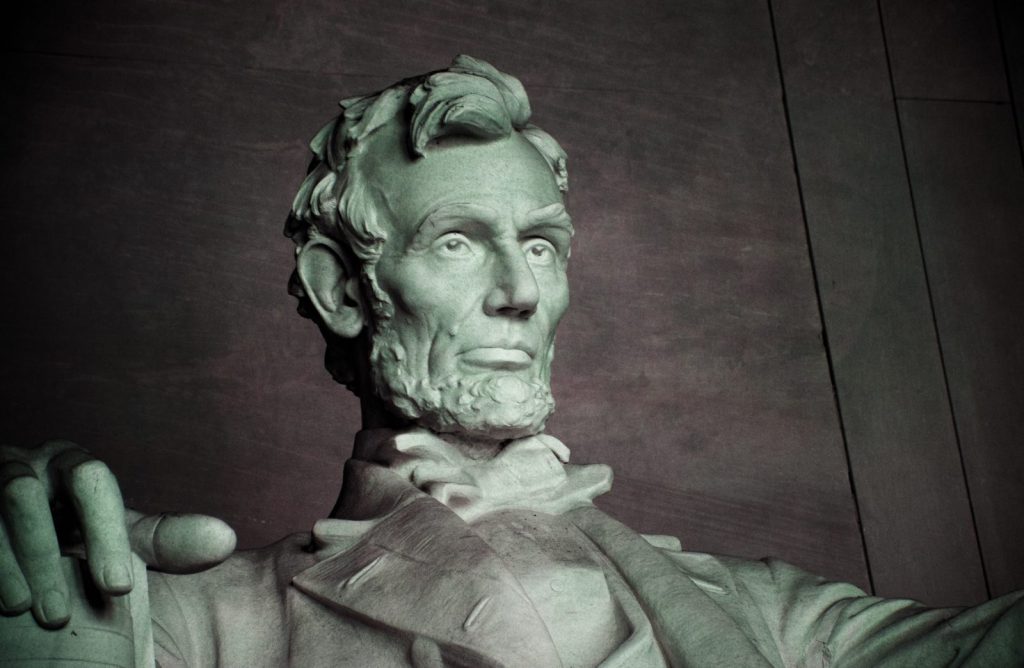

One man’s life and thought were a testament to all three forms of patriotism. Abraham Lincoln, who knew a thing or two about a divided politics, would have been no stranger to our conflicts over national sentiment. But his thinking on that subject offers a model of genuine statesmanship, because it tended to build bridges where others, in his time and ours, could see only chasms.

He suggested, to begin with, that it is a mistake to think of American exceptionalism as a spur to empty jingoism. Our idealistic exceptionalism is, if anything, a restraint on self-congratulation because it always compels us to confront the fact that we fall short of our ideals. The American creed, Lincoln argued in one speech, should form “a standard maxim for free society, which should be familiar to all and revered by all; constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

What makes America exceptional is that it was founded on principles that guide our public life yet will always be aspirational. This joins together the conservative and progressive forms of patriotism — as it suggests that progress toward justice involves vindicating rather than repudiating our founding principles.

Those principles can also help to overcome another challenge to unity in our day that Lincoln would have recognized. As he noted in his 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, about half the people living in the United States at that time were not descended from the founding generation but were immigrants or children of immigrants. They had no connection “by blood” to the revolution, he said. And yet, “when they look through that old Declaration of Independence, they find that those old men say that ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,’ and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh, of the men who wrote that Declaration — and so they are.”

A stirring call to patriotism, to be sure. But Lincoln was also alert to the charge — as present then as now — that this kind of attachment is too cold and theoretical to hold us together in times of genuine strain. The very first sentence of the Declaration of Independence describes us as “one people,” and American patriotism has always been a form of nationalism, too.

Sometimes Lincoln suggested that sheer love of our own — the argument that Trump and some of his supporters have made — might live alongside our patriotism of principle and aspiration, albeit as a junior partner. Of his great hero, Henry Clay, Lincoln said, “He loved his country partly because it was his own country, but mostly because it was a free country.”

In his youth, in particular, Lincoln inclined toward a rather cerebral form of patriotism. In one of his earliest public addresses, delivered before the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Ill., when he was only 28, he suggested that, even in the face of passionate divisions, our commitment to America should be unfailingly rational. The revolution was over, he suggested. “Passion has helped us; but can do so no more. It will in future be our enemy. Reason — cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason — must furnish all the materials for our future support and defense. Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the Constitution and laws.”

But 23 years later, as he prepared to take on the heavy burden of the presidency amid deeper and more intense divisions than America had ever known, Lincoln had come to see that pure principle and reason alone were not enough of a foundation for reverence, unity and love of country. True, an excess of passion was dangerous. But at the conclusion of his first inaugural address, he called for something more lyrical and sentimental to bind us: “Though passion may have strained, it must not break, our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

Lincoln had discovered for us the truest touchstone of republican patriotism: the unifying power of our common national memory. Memory is both conceptual and visceral. It lets us take pride in our ideals and our experience — our origins and our progress — and the fact that both are ours. It can serve as a fountain of affection because it is shared with our fellow citizens, not simply as a set of principles but as a life lived together.

A patriotism of common national memory could be the answer to the riddle of a politics divided over how to be unified. It is not a way to make our differences go away, but rather to allow us better to live with them and so with each other. It could help counteract our tendency to think of our political opponents as speaking from outside the American tradition, and so as threats to be warded off rather than fellow citizens to be engaged. Our tradition is more capacious than we tend to imagine and gives us more room for genuine politics than we too often assume.

A love of country rooted in national memory would let us draw some good out of the ways in which we are now divided over patriotism. It is good for all of us to be reminded of the ideals America was born to embody, of the fact that it could stand to embody them more fully, of the fact that all these ideals can be embodied at the same time, and of the simple reality that America is not itself an ideal but a real nation, full of real people who deserve leaders who put them first.

And it would be good to remember, as well, that our country has made it through moments of much deeper division than this one — in the lifetimes of many Americans, let alone in the span of our national memory. We have often done so with the help of leaders able to summon us toward progress rooted in remembrance. We could sure use such leaders now.

So as we celebrate our country this Independence Day, let’s cite Lincoln once more. He concluded his eulogy of Henry Clay with a prayer to which he himself would one day be an answer and which we would be wise now to repeat: “Let us strive to deserve, as far as mortals may, the continued care of Divine Providence, trusting that, in future national emergencies, He will not fail to provide us the instruments of safety and security.”

Amen.

Yuval Levin, the editor of National Affairs, is the Hertog fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.