Published July 5, 2019

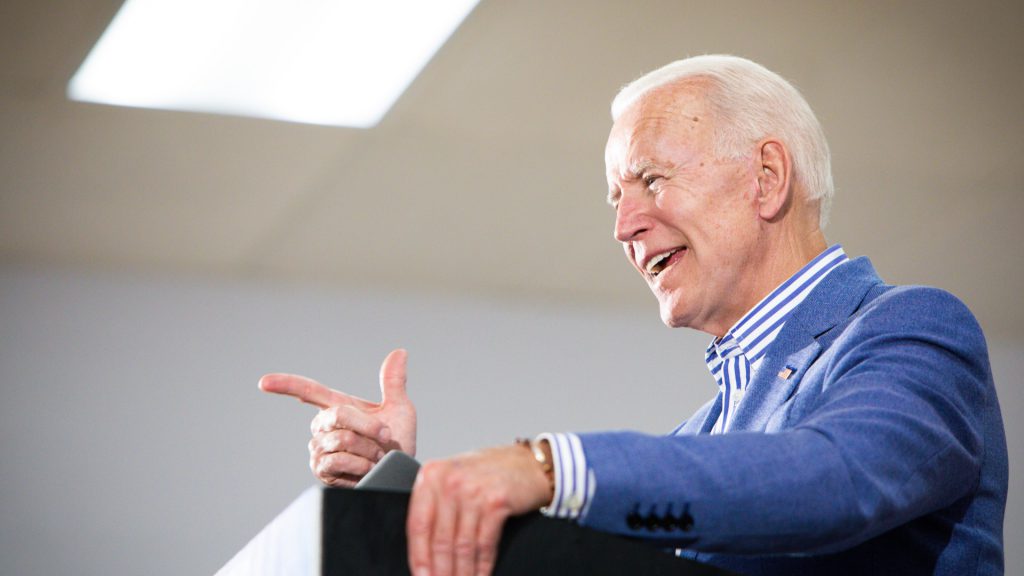

Senator Kamala Harris demonstrated rare skill during the debate — managing to shiv Joe Biden and look nice doing it. By adopting the language of “hurt” instead of anger, she finessed the problem that usually attends launching an unprovoked attack; that it may harm the perpetrator as much as the target — think Chris Christie and Marco Rubio in 2016. Harris’s pose of wounded disappointment shielded her, at least until her roll out of $35 T-shirts the following morning, featuring the image of herself as a child. That revealed, shall we say, a certain calculation.

Still, Harris’s maneuver achieved its purpose, vaulting her into the top tier of Democratic candidates. The price will come later. Many on the left are now combing over Joe Biden’s record on busing and crime, mining it for nuggets that can make him seem if not quite racist, then insufficiently sensitive for the 21st century. Harris demanded that Biden acknowledge that it was a mistake to oppose busing in the 1970s and ’80s. And Cory Booker, no doubt cursing fate that he was slotted in the first debate and thus missed his chance to be the black candidate who could skewer the frontrunner, has issued post-hoc fighting words: “I think Joe Biden is going to have to talk a lot about his record during this election, and I think it’s only right that he talk about everything from his support of the 1994 crime bill . . . all the way to his stance on busing.”

Hoo boy. To review, some or most of the 2020 Democrats now support: eliminating private medical insurance, making it merely a traffic fine to cross the border, extending full health coverage to illegal aliens, paying off everyone’s student debt, providing “free” college and universal pre-K, offering reparations for slavery and to same-sex couples who couldn’t marry until 2015, providing Medicare for All, and forced busing.

The pile on over the 1994 crime bill (which, at the time, many leading black politicians supported) is just around the corner.

This is a strategic and a policy mistake by the Democrats. Strategy first.

Busing to achieve racial integration was always deeply unpopular. In 1972, a Gallup poll found that only 20 percent of respondents favored “compulsory busing of some children both black and white so that school desegregation can be achieved.” Seventy percent opposed it. Do Democrats want to wear this around their necks in 2020?

Now to policy: Some resistance to busing was doubtless motivated by racism, but it’s wrong to assume that racism was the whole story. In the 1950s, most white Americans favored separate schools. But since the 1960s, majorities of both black and white Americans have supported integrated schools, and overwhelming majorities since the 1980s. A Public Opinion Quarterly study found that in 2004, 83 percent of parents would choose a school that was “mostly mixed” as their ideal. But when they were asked if they supported busing to achieve this, support for diverse schools plummeted.

Even among black parents, support for busing was tepid. A 1998 survey found that only 55 percent of African-American parents favored busing to achieve racial balance in schools. Larger majorities favored redrawing district lines (69 percent), letting parents choose their top three schools (65 percent), or building more low-cost housing in middle-class neighborhoods (84 percent) to achieve the same goal.

Schools with majority minority students aren’t bad schools because of the students (many charter schools are doing well), they’re bad because parents aren’t as involved as those in suburbs and because teachers’ unions make it difficult to offer choice. Many inner-city schools are also plagued by discipline problems and violence. Labeling suburban parents who don’t want their kids bused to these schools as racist is unjust.

As always, the law of unintended consequences has the last word. Jeff Jacoby of the Boston Globe reminds us that in 1970, before Boston’s disastrous experiment with busing, 62,000 white students attended public schools. By 1994, only 11,000 did. The likelihood that a minority student would have white classmates declined sharply after busing, as “white flight” increased de facto segregation.

Busing was bad policy but, oh yeah, it was also unpopular. Way to go Democrats.

© 2019 CREATORS.COM

Mona Charen is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center.