Published December 17, 2021

(This post originally appeared in Aaron Kheriaty’s Substack newsletter “Human Flourishing.” Read other issues and subscribe to the newsletter here.)

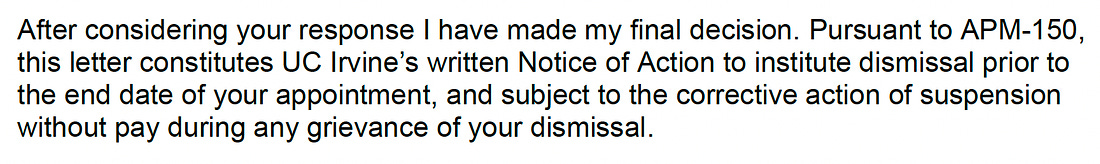

Yesterday I received the following notice from the University of California, effective immediately, where I have served for almost fifteen years as Professor at UCI School of Medicine and Director of the Medical Ethics Program at UCI Health:

This termination has been an opportunity for me to reflect on my time at UCI, especially my time there during the Covid pandemic. Two years ago I never could have imagined that the University would dismiss me and other doctors, nurses, faculty, staff, and students for this arbitrary and capricious reason. I want to share a bit of my story, not because I am unique but simply because my experience is representative of what many others—who do not necessarily have a public voice—have experienced since these mandates went into effect.

I worked in-person at the hospital every day during the pandemic, seeing patients in our clinic, psychiatric wards, emergency room, and hospital wards—including Covid patients in the ER, ICU, and medicine wards. As our chief ethics consultant, I had countless conversations with families of patients dying of Covid, and tried my best to console and guide them in their grief. When our pregnant residents were worried about consulting on Covid patients, the administration reassured these residents that they had no elevated risks from Covid—a claim without any evidential basis at the time, and which we now know to be false. I saw the Covid consults for these worried residents, even when I was not covering the consult service.

I also remember in the early weeks of the pandemic when N-95 masks were in short supply and the hospital kept them under lock and key. Hospital administrators yelled at nurses for wearing surgical or cloth masks (this was before masks became all the rage after the CDC suggested, with little evidence, that they might help). At that early stage the truth was we didn’t know whether masks worked or not, and nurses were doing the best they could under pressure in a situation of uncertainty. The administrators yelled and ridiculed them, not wanting to admit the real issue was that we simply did not have enough masks. So I called local construction companies and sourced 600 N-95s from them. I supplied some to the residents in our department and my attending colleagues in the ER, then donated the rest to the hospital. Meanwhile the University administrators—the same ones who fired me yesterday—were working safely from home and did not have to fret about PPE shortages.

In 2020 I worked nights and weekends, uncompensated, helping the UC Office of the President draft the UC policies for triaging scarce resources and allocating vaccines during the pandemic. Knowing that our ventilator triage policy was publicly sensitive, the Office of the President asked me and the chair of the drafting committee to serve as public spokespersons to answer questions about this policy and explain the principles and rationale to the public (they even provided me with media training).

I was the only faculty member at UCI who directed courses across all four years of our medical student curriculum, so I knew the students as well as anyone at the University. The Dean asked me to address the students when they were first sent home in the early days of the pandemic. While I disagreed with the decision to send them home—after all, what were they here for if not to learn to practice medicine, especially during a pandemic?—I nevertheless encouraged them to continue to engage with pandemic response efforts outside the hospital. I published those remarks to encourage students at other schools.

Our dean sent this to the deans at the other UC schools, one of whom suggested that I give the graduation speech at all the campuses that year. Three years ago, the UCI school of medicine deans asked me to give the White Coat Ceremony keynote address to the incoming medical students because, as they told me, “you are the best lecturer in the medical school.” For many years, the psychiatry clerkship I directed was the highest rated clinical course at the medical school.

Everyone at the University seemed to be a fan of my work until suddenly they were not. Once I challenged one of their policies I immediately became a “threat to the health and safety of the community.” No amount of empirical evidence about natural immunity or vaccine safety and efficacy mattered at all. The University’s leadership was not interested in scientific debate or ethical deliberation. When I was placed on unpaid suspension I was not permitted to use my paid time off—that is to say, I was ordered to stay off campus because I was not vaccinated, but I also could not take vacation at home because… I was not vaccinated. In violation of every basic principle of just and fair employment, the University tried to prevent me from doing any outside professional activities while I was on unpaid suspension. In an effort to pressure me to resign, they wanted to restrict my ability to earn an income not only at the University but outside the University as well. It was dizzying and at times surreal.

Now it’s officially over. I do not regret my time at the University. Indeed, I will miss my colleagues, the residents, and the medical students. I will miss teaching and supervising and doing ethics consults on some of the most challenging cases in the hospital. As I wrote to my colleagues at the University earlier this week:

While this is not how I pictured saying goodbye, I wanted to at least write to all of you before my access to your email addresses is shut down. It has been a pleasure and an honor to work with all of you during my fifteen years at UCI, and with many of you as far back as my four years of residency training at UCI. I love academic medicine and had hoped to stay at UCI until retirement, but that is not in the cards. Since being placed on leave on October 1, I have missed all very much and I hope that you all have been doing well. I apologize for any inconvenience that my absence has caused my fellow attendings who are covering my clinical/teaching duties or the residents that I was supervising.

To the residents, it’s been a tremendous priviledge teaching and supervising you. Our program is fortunate to have such dedicated and talented residents, and I am confident that all of you will thrive in your careers. Thank you for your dedication to teaching our medical students. To the attendings, you are a tremendous group of colleagues and friends. I will very much miss working with all of you. I’ve learned a lot from every one of you, and I know that our department will continue to flourish as long as this group of attendings continues to anchor the clinical, teaching, and research enterprises. I write this literally with tears, and will maintain many fond memories of my time working with all of you. To the staff, you are terrific and so essential to everything we do. Thank you for all your dedicated work on behalf of our patients, students, residents, fellows, and attendings—and a for all the help you’ve provided to me every day.

I would have reached out to all of you sooner but was ordered by the University not to conduct any University-related business after being placed on leave on October 1, and I have not been allowed to return to campus since then (except to move out of my office). The University maintains that my termination is unrelated to my lawsuit challenging the UC vaccine mandate in federal court on behalf of covid-recovered individuals with infection-induced (natural) immunity. The decision to terminate me comes from the UC Office of the President and not from our department. I have nothing but gratitude and goodwill toward our department leadership and toward everyone at UCI. Indeed, I bear no resentment toward anyone at UC, including the people who twice denied my medical exemption or those who chose to fire me. Life is too short to bear a grudge.

I likewise want to thank all of you readers for your support and encouragement over the past several months. I trust that other doors and new opportunities will open up for me in the New Year as I transition into private practice and expand my work at the Zephyr Institute, where I direct the Health and Human Flourishing Program, and the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where I direct the Bioethics and American Democracy Program.

Now, since my university titles are gone I need to go update my bio on this site and on my website—where you can, by the way, find many of my old writings, interviews, and talks. I’ll be sending an update next week on my lawsuit and also on the Pfizer documents we recently received from the FDA, so stay tuned.

Aaron Kheriaty is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he directs EPPC’s program in Bioethics and American Democracy.

Aaron Kheriaty, MD, is a Fellow & Director of the Program in Bioethics and American Democracy at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He is a physician specializing in psychiatry and author of three books, including most recently, The New Abnormal: The Rise of the Biomedical Security State (2022).