Published November 3, 2021

Introduction

As educational attainment continues rising, the presumed price of admission to the middle class increasingly seems to require a college degree. In the United States, more young adults than ever attend college, and more young adults than ever rely on student loans. The percentage of all households with any outstanding student loan debt rose from 8.9 percent in 1989 to 21.4 percent in 2019.[1] And from 2006 to 2020, the average amount of outstanding student loan debt per working-age American grew from under $4,000 to over $13,000.[2]

At the same time, a growing cultural emphasis on “individual financial and personal responsibility as a necessary precursor for marriage” has led to a profound shift in attitudes towards family formation.[3] Marriage has become more of a “capstone,” signaling a full transition into adulthood, and less of a “cornerstone,” on which young couples begin to build a life together.[4]

These two facts have led many to associate rising student loan burdens with delayed marriage and parenthood.[5] A study by a private student loan lender found that roughly one-third of adults who attended college “might” consider delaying marriage due to education-related debt.[6] “How could I consider having children if I can barely support myself?” asked one Chicago woman who graduated from a for-profit interior design school with six figures of debt.[7]

But declining marriage and fertility rates are happening across the board, while student loan burdens are less widespread. According to the Federal Reserve, 70 percent of all U.S. adults, including 57 percent of those who attended college, have never incurred education-related debt.[8] A full two-thirds of the Millennial generation, who came of age during the rapid run-up in education-related debt, hold no student loan debt.[9]

Additionally, education-related debt is an investment as well as an obligation. Paying for higher education through student loans is one way of increasing human capital, and this makes it both a liability and an asset.

The Social Capital Project has identified “making it more affordable to raise a family” as one of the core goals of our work. [10] Proposals to reduce or eliminate student debt on a large scale are often proposed in the spirit of lifting barriers to family formation, allowing young adults to marry or become parents.[11] But understanding what role student debt plays in the lives of young Americans is important before adopting widespread policy prescriptions.

Careful consideration of the research suggests that some individuals with exceptionally high loan burdens, particularly women, are more likely to delay marriage. There is less evidence that student loans are associated with lower fertility. And on balance, large debt burdens are largely shouldered by a largely self-selected subset of households, many with higher educational attainment and higher earning potential.

Still, no one wants young adults to be overly burdened by student loans. Income-based repayment can be improved, particularly for individuals who did not finish college or who are underemployed. Supporting community college, trade schools, and non-traditional pathways to the workforce, and encouraging more competition in higher education, would help more young people increase their options without overreliance on debt.

This paper will weigh the extent to which student loan debt may be interfering with young adults’ desire to get married and start a family, before concluding with a brief exploration of related public policy options.

The Evolution of Student Debt

Increasing Attendance, Rising Costs

Some form of college education has become the norm for a majority of young adults. Ever since 1988, more young adults than not have been enrolled full- or part-time in an institution of higher education, with the share of young adults enrolled in college plateauing somewhat in the early 2010s.

Figure 1: Enrollment in degree-granting post-secondary institutions, by type

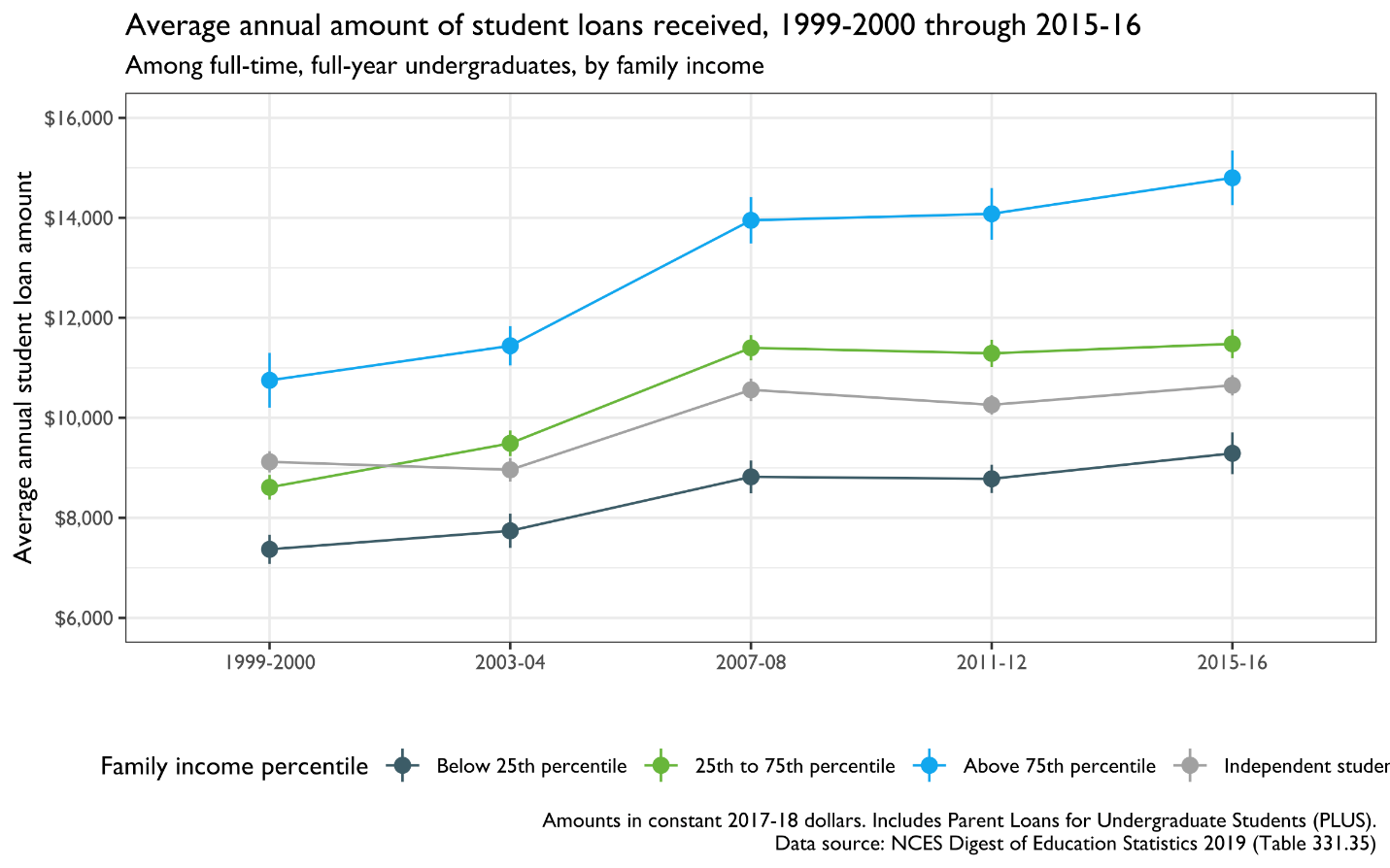

College has also become more expensive. The average sticker price for tuition, fees, room, and board (TFRB) facing a full-time student at a four-year, public university doubled from 1992 to 2018.[12] The reason for the increasing costs are multifaceted. For one, amenities have improved – room and board costs at a four-year university have more than doubled, in constant dollars, since 1980.[13] Additionally, new administrative positions, some tied to regulatory compliance, have pushed up colleges’ operating costs; the number of administrative and managerial staff at private four-year universities doubled from 1991 to 2011.[14] Finally, colleges may also have gotten better at price discrimination, the economic term for charging according to a consumer’s ability to pay; among full-time undergraduates, the rise in prevalence and average size of student loans is most notable among families in the top income quartile, as seen in Figure 2.[15]

Another explanation for rising tuition is that increases in federal education loans are responsible for subsequent rises in tuition. This idea is known as the Bennett Hypothesis, after President Reagan’s Secretary of Education William Bennett, who first proposed it in 1987.[16] Ever since, researchers have sought to empirically isolate the effect of increasing federal aid on tuition, with different papers reaching varying results.

As Texas Public Policy Foundation scholar Andrew Gillen has written, “‘Is the Bennett Hypothesis true?’ is the wrong question as it has no consistent answer. The better question is, ‘When does the Bennett Hypothesis hold or not hold, and why?’”[17] One paper found distinct evidence for the Bennett hypothesis in for-profit programs offering certificate programs; institutions that participated in federal student aid programs charged tuition that was 78 percent higher than comparable programs in institutions that did not participate.[18] Another paper found evidence to suggest an effect on “more expensive degrees, those offered by private institutions, and for two-year or vocational programs.”[19]

Another form of federal subsidy for higher education comes in the form of parent PLUS loans. These loans are only available to parents of undergraduate students, and unlike undergraduate loans, there is no set maximum loan. As such, parents can borrow up to the full cost of attendance, with even less cost discipline in this form of loan than in other programs. According to a Brookings Institution paper, “the average annual borrowing amount for parent borrowers has more than tripled over the last 25 years, from $5,200 per year in 1990 (adjusted for inflation) to $16,100 in 2014.” The paper suggests these uncapped loans increased access to credit for institutions and programs that may otherwise have had to lower tuition or take other measures to appeal to students.[20]

Although the sticker price for undergraduate education has increased, actual out-of-pocket costs for families have risen at a much slower pace. This helps explain why over the past two decades, room and board expenses have risen steadily for all students, but families making below the median income have seen out-of-pocket spending on tuition and fees remain largely stable.[21] Meanwhile, the share of students who received student loans rose from 45.6 to 54.7 percent from 2000 to 2015, with the average annual loan amount rising from $8,840 to $11,610 (in 2017-18 dollars.)[22]

Figure 2: Percentage of college students receiving student loans, 1999-2016

A 2015 Brookings paper provides a closer look at student debt burdens. Using tax data, it finds that median annual borrowing for education-related debt has gradually risen for undergraduate borrowing since the 1980s, especially for students who attended selective four-year institutions.[23]

Figure 3: Average outstanding federal loan balances upon repayment

As Figure 3 indicates, the bulk of the increase in student debt is driven by graduate loans, on both the intensive and extensive margin. More people are attending graduate school, and taking out more loans to do so. Full-time enrollment in graduate programs increased nearly two-thirds from 2000 to 2018,[24] and the average amount of cumulative borrowing (including undergraduate debt) for those who borrowed for graduate school rose from $62,720 in 2000 to $85,830 in 2016.[25]

Repayments and Defaults

For many people, taking on student loan debt can be a rational decision to smooth consumption over the lifecycle and achieve greater educational attainment with an assumed wage premium.[26] In this sense, education-related debt is a long-term investment, and thus a kind of asset. However, because the rewards to a college degree are uncertain, it is a somewhat-riskier asset with a deferred and variable payoff.[27]

Rising balances may be cause for concern, but less so if increased earnings make it possible to pay the amount owed. However, many students do not graduate, or are underemployed after graduation. Student loans are generally not dischargeable in bankruptcy and often require payments regardless of income, with some exceptions noted below. “Reflecting this uncertainty, over two-thirds of college students carrying debt report being either very or extremely anxious about their college debts,” found one study.[28]

Meanwhile, default rates are most strongly associated with the earnings profile of the borrower and the institution they attended, not the size of the loan balance.[29] Borrowers with the most debt, often from post-baccalaureate studies or highly selective colleges, are statistically the least likely to default.[30] The Federal Reserve found that adults who attended a for-profit college are nearly three times more likely to be behind in repayment relative to those who attended a public college or university.[31] In short, a Brookings paper notes, if “there is a crisis, it is concentrated among borrowers who attended for-profit schools and, to a lesser extent, 2-year institutions and certain other nonselective institutions” – not the six-figure loan balances from elite programs that receive media attention.[32]

Additionally, as the Urban Institute’s Sandy Baum notes, “Federal student loans are probably the only category of debt for which there is already a system in place to suspend payments when borrowers’ incomes will not support them.”[33] Income-driven repayment (IDR) plans limit monthly payments to a set percentage of income (often 10 percent of income above 150 percent of the federal poverty level) with any unpaid balance forgiven after 20 to 25 years. About one-third of student loan borrowers in repayment are enrolled in an IDR plan, though the current federal structure of these programs is fragmented and often bureaucratically onerous for borrowers.[34] IDR plans offer policymakers a way to target relief to low- and middle-income borrowers in a way that proposals for blanket loan forgiveness proposals do not.

Evaluating the Evidence

Although debt and default rates may not be at crisis levels, the timing of student debt in the lifecycle may merit special consideration. Student loans require repayment in the years after an individual leaves college, which coincides with the prime years for family formation, so debt burdens may be holding young adults back and preventing them from forming families. More young adults than ever before are taking on education-related debt, which could directly affect household formation, delaying marriage and reducing fertility.[35]

Nevertheless, certain facts complicate the story as an explanation for declines in family formation overall: for example, declining marriage and fertility rates predate the large growth in student loans, and occur across all levels of educational attainment.[36] Moreover, whereas in prior generations more-educated women would marry later, the average age at first marriage has increased and converged across all groups by educational attainment.[37]

The Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) provides relevant descriptive information, and shows the rise in student debt over the past three decades by family type.[38] For households headed by someone aged 22-50, the percentage of households reporting any student loan debt increased from 13.2 to 35.7 percent over the last three decades. [39] In 2019, the average loan balance for married or cohabiting couples (with a head of household below age 50) with any outstanding loans approached $50,000, and this tended to exceed non-married/non-cohabiting households’ average loan balance slightly (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average value of outstanding student loan balance held by households, 1989-2019

Note: Figure 4 demonstrates how large values in the distribution’s tail can pull the average student loan balance upward. In this figure, the mathematical average (mean), is plotted alongside the statistical midpoint of the data (median). The median suggests a much flatter rise in outstanding loan debt than the mean.

Some individuals may have higher earnings profiles and may pay their loans back more quickly, so Figure 5 includes all households to account for this. Even including all households, married households tend to have slightly more student loan debt than unmarried ones overall. Households headed by a graduate degree holder are the exception to the rule and tend to have lower debt levels if they are married, which is what we would expect to see if graduate degree holders with high loan balances are less likely to marry.

Figure 5: Average value of education loans held by household, 1989-2019

Data sorted by number of children and highest education level attained shows the dramatic increase in student loan debt among graduate degree-holding households, and the highest loan balances are found among childless households (Figure 6). This corresponds to what we would expect to see if high cumulative debt loads had a negative impact on fertility. On the other hand, there appears to be no difference in debt levels across number of children in the household for households with less than a Bachelor’s degree. And among households headed by an adult with a bachelor’s degree, there may be an emerging differential in debt for families with two or more children compared to families with zero or one child since 2013, but the association between more children and less debt is far from clear-cut.

Figure 6: Average outstanding loan balance among households with student debt, 1989-2019

In summary, descriptive information suggests that graduate degree holders hold the highest average cumulative student loan debt, and graduate degree holders with the highest cumulative debt are less likely to have children or be married. However, disentangling whether those who are more career or self-oriented may be more likely to pursue advanced degrees, avoid marriage, and have fewer kids is a question that simple descriptive analysis cannot answer. And for households with other educational attainment levels, a link between debt and family formation outcomes is far from clear-cut.

The growth in student loan debt may or may not be grounds for a policy response in and of itself, but growing student loan debt would be a more compelling reason for action if researchers understood the relationship between debt and reductions in marriage or fertility more comprehensively. While the previous analysis relied on descriptive analysis, the following sections explore the academic literature on these topics in more detail.

Student loan debt and delayed marriage

The first question is to what degree student loan debt influences marriage rates and timing. Different studies have found suggestive evidence, to varying degrees, that student loans affect marriage. One frequently cited paper found that “controlling for age and education, both men and women are less likely to marry if they hold student loans.” However, that study examined the marital choices of college graduates taking the GMAT as a precursor to a graduate business degree, which may reflect some degree of self-selection.[40] Another paper found that female law school graduates with high debt burdens – again, a select group – were more likely to postpone marriage than those with low amounts of debt.[41] An older study found no relationship between debt and marital status, among undergraduates graduating in the early 1990s.[42]

These papers, however, pre-date the Great Recession, during which 14 percent of college students said that they had delayed marriage or a committed relationship because of their student loan burden.[43] A more recent study of undergraduates who entered the job market in the middle of the Great Recession found that each additional $5,000 in student loans was associated with a 7.8 percentage point lower likelihood of having married, which could reflect the credit-constrained, adverse job market graduates faced.[44]

A similar study found student loan debt is linked to delayed marriage, especially for women, those majoring in health care, residents of areas with higher unemployment rates, and for graduates with more educated parents.[45] While these studies face some methodological questions, they suggest that student loans did not negatively affect marriage decisions in prior generations, but may do so now.[46]

Figure 7: Mean educational loan debt held by first union type, by sex

Ethnographic work suggests that debt could be considered a barrier to marriage but not cohabitation.[47] Drawing on Andrew Cherlin’s work on the “deinstitutionalization of marriage,”[48] University of Wisconsin sociologist Fernanda Addo notes that in marriage, individual debts brought into a union become the responsibility of both members, whereas in less-formal relationships, like cohabitation, the debt remains the responsibility of the individual who incurred it. “If young adults prefer to be financially established prior to marriage, cohabitation will be more likely if debt is high, and marriage will be more likely if debt is low or nonexistent.”[49]

Using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY), Addo finds that young women who cohabited before marriage were most likely to have student debt, while young women who married without cohabitation had the lowest average student debt load. She estimates that each additional 1 percent in student loan debt is associated with a 2 percent reduction in the likelihood of being married for women. However, no similar pattern existed for men.[50]

Another paper found a similar estimate, with each additional $1,000 in debt tied to a one percent decline in likelihood of marriage, but again “the negative relationship between remaining debt and the odds of first marriage held for women only.” The authors note that “there are fewer college-educated men in the population, and so their demand in the marriage market may trump their earnings or debt as signals of marriageable mates.”[51]

Different logic could be at work for young men and young women.[52] For instance, some couples contemplating starting a family may believe that the woman is more likely to withdraw from the labor force after childbirth, at least temporarily, which could lead men to have a preference for relatively debt-free spouses. This could lead to a preference for cohabitation while there is debt outstanding, as financially-independent individuals progress towards marriage without taking on the joint burden of assuming each other’s debts in marriage.

Importantly, Addo finds that marriage rates following a period of cohabitation remain unrelated to student debt. Instead, she finds suggestive evidence that increasing debt balances have only reduced “direct marriage (and not marriage preceded by cohabitation)” for young women.[53]

It may be that student loan debt is not leading young women to opt for cohabitation over marriage, but student loan debt is introducing premarital cohabitation as an extra stop on the pathway to marriage. This could contribute to the increasing average age at first marriage and reduce the number of years available to couples who wish to have children in wedlock, as cohabitation is a less-stable type of union.[54]

Student loan debt and reduced fertility

In addition to student loan debt’s relationship with marriage, the relationship between student loan debt and fertility is an important question for family affordability. However, in this area research has struggled to find a consistent story, with multiple scholars failing to reach consensus on the direction or magnitude of any impact. A 2019 working paper found student loan balances were not statistically significantly associated with fertility in the first four years after graduation.[55] Another paper, resting on controvertible assumptions, found each additional $5,000 in student loan debt was associated with graduates being 5 percentage points less likely to have a child, though the finding was only statistically significant for females.[56]

One of the more reliable papers to examine the question uses the NLSY, and finds each additional $1,000 in student loans is associated with a 1.2 percent decrease in the annual likelihood of having a child. Women with $60,000 in student loan debt were 42 percent less likely to have a child in any given year compared to women with no debt (2.5 percent likelihood, compared to 4.3 percent.)[57] “Student loans may not have noticeable effects on fertility at moderate levels,” the paper notes, but “these effects can be quite substantial at high levels.” But most student loan balances do not approach that magnitude – only 9 percent of women at age 25 had outstanding loans that large in their sample.

The authors note the importance of self-selection, and the fact that women who choose to pursue advanced degrees may be “qualitatively different, and that the career payoff compensating for this level of debt may take even longer than for more moderate debt levels.” Women with high levels of debt, often due to graduate school, may be making an intentional tradeoff between early career advancement and fertility. In sum, the authors find, it is “unlikely that indebtedness would be sufficiently large (for most) to significantly change the decision to have children at all, but may affect the timing of fertility.”[58]

There may be another factor contributing to the limited relationship between student loan debt and fertility—especially as compared to the intentionality behind a decision to get married, “the transition to parenthood can occur even in cases where individuals have not planned to become parents, and thus material readiness may not always be the most salient factor predicting the transition. This potential for accidental transitions may in effect diminish the role of financial security.”[59]

Other factors beyond a person’s control can also impact the decision to become a parent as well – when Robb and Schreiber control both for household income and macroeconomic conditions, “student loans are not significantly associated with the transition to parenthood.”[60]

Potential Avenues for Policymakers

The evidence suggests that the decision to marry may be impacted by our ongoing shift to a debt-financed model of human capital formation, with a more tenuous case that student debt may impact parenthood, as well. The reasons behind this shift, which could include greater emphasis on professional fulfillment over marriage and higher opportunity costs to parenthood, may be beyond the ability of policy to affect directly.

But opportunities exist to shift existing policies on the margins to make it less difficult for individuals who want to form families to do so. Policymakers could make it easier for individuals to weigh the trade-offs associated with higher education, promote competition in higher education, and reform payment options to make it more affordable for individuals to have a family and pursue their education.

One potential option is to double the student debt interest deduction in the tax code from $2,500 to $5,000 for married filers, ensuring that couples do not face an implicit penalty in choosing to marry.[61] The Lifetime Learning Credit, which allows taxpayers to deduct qualified education-related expenses such as tuition and textbooks, is currently capped at $2,000 per return; it could also be doubled for married filers to minimize associated marriage penalties.[62] However, if policymakers are interested in rectifying the root of the issue, then they should eliminate marriage penalties and check tuition costs through removing the tax structures that create these issues in the first place.

Streamlining income-driven repayment (IDR) could be an easier way to direct assistance to those in difficult financial circumstances.[63] IDR, which sets monthly student loan payment at an amount deemed “affordable” based on income and family size, can be improved for newly-married households and those with children. Repayment plans tied to income have been implemented in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom,[64] and have been supported conceptually by economists from Milton Friedman to James Tobin, two Nobel laureates who occupied opposing ends of the political spectrum.[65]

Multiple pieces of legislation that would streamline the current mix of four IDR options into one, simplified program have been introduced on both sides of the aisle and included in the President’s budget in FY2018, FY2019, and FY2020.[66] Importantly for the purposes of this paper, income-driven repayment programs often penalize couples upon marriage. Under current law, married couples that file jointly would have a higher adjusted gross income (AGI), and therefore a higher amount owed, than if they hadn’t married, and could possibly become ineligible for IDR (couples can still file separately, but would lose out on other benefits of joint filing). Any reform of IDR programs should find ways to soften marriage penalties for couples filing jointly, such as introducing a set-aside of some spousal income in calculating joint AGI, doubling the IDR eligibility cutoff for newly-combined incomes, or otherwise adjusting the expected contribution for families in IDR programs.

More broadly, eliminating marriage penalties in the tax code or further increasing the Child Tax Credit would be a way to provide benefits to all families, regardless of student loan balance.[67] Not all of the steps to address any effects of student debt on family formation need come from Washington, D.C. Given the balance of evidence shows student loan burdens associated with declines in marriage, philanthropic organizations and private industry could focus some efforts on providing interest rate reduction or balance forgiveness following a marriage. University administrations, especially in graduate programs, could ensure that stipend or financial aid calculations are adjusted for household size, and expand the generosity of financial supports and services for families to better support students that choose to marry or have children in school.[68]

While this paper focuses specifically on student debt as it relates to family formation, multiple proposals have been introduced to make higher education more affordable across the board. Notably, the Higher Education Reform Opportunity (HERO) Act introduced by JEC Chairman Sen. Mike Lee, proposes a number of policy mechanisms to lower college costs through increased competition and transparency.

The HERO Act would lower barriers to entry for new educational models by encouraging accreditation reform to allow for innovative, non-traditional approaches to credentialing; building on ongoing efforts to make transparent scorecards available on earnings by major and by institution, making it easier for students and their parents to “comparison shop” across competing programs; consolidating and capping existing student loan programs; and introducing a “skin-in-the-game” measure for universities and colleges.[69]

Capping or eliminating PLUS loans, including Parent-PLUS loans for post-baccalaureate students and Grad-PLUS loans, could also instill more discipline in graduate school debt.[70] Congress could restrict or eliminate Parent-PLUS loans, which encourage families with undergraduates to take on debt and serve as “a no-strings-attached revenue source for colleges and universities, with the risk shared only by parents and the government.”[71] A bolder step would be to introduce per-student, per-year caps into federal student loan programs; the Heritage Foundation estimates such a plan could reduce total federal student lending by one-third.[72] Introducing more price discipline to higher education could take the form of ensuring that career and technical education pathways, such as registered apprenticeships, are available to young adults who want to pursue careers that do not require degrees.[73]

Another alternative could include broadening access to income-share agreements (ISA), which offer an alternative pathway to financing higher education, particularly for students studying majors in high demand.[74] As opposed to IDR, ISAs do not entail taking on a balance or paying interest; instead, a student promises to pay a certain percentage of their future income to an investor. Some institutions, notably Purdue University, have begun to offer ISAs for certain fields of study.[75] Congress could clarify that it is acceptable for schools to provide ISAs, as proposed last Congress by Senator Young.[76]

Conclusion

Our current model of human capital formation has the potential to subtly nudge young adults to put off pursuing meaningful relationships, marrying, and becoming a parent. We should be creative in exploring alternatives, whether it be income-driven repayment, making marginal changes in the tax code, increasing options both inside and out of traditional higher education, and providing more social support for parents.

But a problem can be a problem without being a crisis. Relying on outlier-inflated means as an excuse for forgiving large amounts of student debt paints a misleading picture. The decisions of individuals to put off marriage or parenthood while pursuing a medical, business, law, or graduate degree is important to distinguish from a popular narrative that paints a rising tide of red ink preventing the modal young adult from starting a family.[77]

Policymakers should keep the goal of broadening the choice set available to individuals in mind. The steps suggested in this paper could make it easier for all young adults to pursue appropriate education without being burdened by debt and having to sacrifice other, invaluable, parts of life in the process.

Footnotes

[1] Survey of Consumer Finances – Extract File 1989-2019, analyzed with UC-Berkeley SDA: Survey Documentation and Analysis, https://sda.berkeley.edu/sdaweb/analysis/?dataset=scfcomb2019

[2] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Student Loans Owned and Securitized, Outstanding,” and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Working Age Population: Aged 25-54: All Persons for the United States,” retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (accessed Dec. 2, 2020.)

[3] Fenaba R. Addo, “Debt, Cohabitation, and Marriage in Young Adulthood,” Demography vol. 51:5 (2014): 1677-701. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0333-6

[4] See, inter alia, Andrew J. Cherlin (2014), Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

[5] See examples in Christina Curley, “The Burdens of Student Debt: Are Student Loans Keeping Young Adults From Moving on with Life?” personal working paper, presented at American Economic Association 2017 annual conference (Jan. 7, 2017), as well as Claire Cain Miller, “A Baby Bust, Rooted in Economic Insecurity,” New York Times (July 5, 2018), p. B-1. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/05/upshot/americans-are-having-fewer-babies-they-told-us-why.html

[6] “84 Percent of Young Adults Have Never Comparison Shopped for a Student Loan,” LendKey Technologies, Inc. (Jan. 31, 2020), https://www.lendkey.com/press/84-percent-of-young-adults-have-never-comparison-shopped-for-a-student-loan

[7] Sue Shellenbarger, “To Pay Off Loans, Grads Put Off Marriage, Children,” Wall Street Journal (April 17, 2012), https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304818404577350030559887086

[8] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Student Loans and Other Education Debt,” in Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018 – May 2019 https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2019-economic-well-being-of-us-households-in-2018-student-loans-and-other-education-debt.htm

[9] Beth Akers, “Issues 2020: Millennials Aren’t Drowning in Student Debt,” Manhattan Institute (Oct. 10, 2019), https://www.manhattan-institute.org/issues2020-millennials-arent-drowning-in-student-debt

[10] U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee, Social Capital Project, “The Wealth of Relations: Expanding Opportunity by Strengthening Families, Communities, and Civil Society.” Report prepared by Chairman’s staff, 116th Cong., 1st Sess. (April 2019). Social Capital Project Report No. 3-19. https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2019/4/the-wealth-of-relations

[11] E.g., Annie Lowrey, “Go Ahead, Forgive Student Debt,” The Atlantic (Nov. 21, 2020) https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/11/why-biden-should-forgive-student-loan-debt/617171/

[12] Digest of Education Statistics, “Table 330.10. Average undergraduate tuition and fees and room and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level and control of institution: Selected years, 1963-64 through 2018-19,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_330.10.asp

[13] Digest of Education Statistics, Table 330.10.

[14] Digest of Education Statistics, “Table 314.20. Employees in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by sex, employment status, control and level of institution, and primary occupation: Selected years, fall 1991 through fall 2015,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_314.20.asp

[15] Digest of Education Statistics, “Table 331.35. Percentage of full-time, full-year undergraduates receiving financial aid, and average annual amount received, by type and source of aid and selected student characteristics: Selected years, 1999-2000 through 2015-16,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_331.35.asp?current=yes

[16] Jenna Robinson, ”The Bennett Hypothesis at 30,” James G. Martin Center (Dec 2017), Bennett_Hypothesis_Paper_Final-1.pdf (jamesgmartin.center)

[17] Andrew Gillen, “Bennett Hypothesis 2.0,” Regulation (Fall 2016), 2-3, Cato Institute, Washington, D.C. https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2016/9/regulation-v39n3-7.pdf

[18] Stephanie Riegg Cellini and Claudia Goldin. 2014. “Does Federal Student Aid Raise Tuition? New Evidence on For-Profit Colleges.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6 (4): 174-206. DOI: 10.1257/pol.6.4.174

[19] David Lucca, Taylor Nadauld, and Karen Shen, “Credit Supply and the Rise in College Tuition: Evidence from the Expansion in Federal Student Aid Programs,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 733 (Jul 2015; revised Feb 2017) sr733.pdf (newyorkfed.org)

[20] Adam Looney and Vivien Lee, “Parents Are Borrowing More and More to Send Their Kids to College—And Many Are Struggling to Repay,” The Brookings Institution, November 27, 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/research/parents-are-borrowing-more-and-more-to-send-their-kids-to-college-and-many-are-struggling-to-repay/

[21] College Board, “Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid: 2020,” (Oct. 2020), https://research.collegeboard.org/pdf/trends-college-pricing-student-aid-2020.pdf

[22] Digest of Education Statistics, Table 331.35.

[23] Adam Looney and Constantine Yannelis, “A Crisis in Student Loans? How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions They Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall 2015) https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/pdflooneytextfallbpea.pdf

[24] Digest of Education Statistics, “Table 303.80. Total postbaccalaureate fall enrollment in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by attendance status, sex of student, and control of institution: 1970 through 2029,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_303.80.asp?current=yes

[25] The amounts are in constant 2018-19 dollars. Digest of Education Statistics, “Table 332.10. Amount borrowed, aid status, and sources of aid for full-time, full-year postbaccalaureate students, by level of study and control and level of institution: Selected years, 1992-93 through 2015-16,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_332.10.asp?current=yes

[26] The gap between the median college-educated and median high-school educated workers roughly doubled between 1979 and 2012. See David H. Autor, “Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the ‘other 99 percent,’” Science, vol. 344, iss. 6186 (May 23, 2014), 843-851, https://economics.mit.edu/files/11554

[27] Michael Nau, Rachel E. Dwyer, and Randy Hodson, “Can’t Afford a Baby? Debt and Young Americans,” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, Vol. 42 (Dec. 2015), 114-122, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2015.05.003

[28] Nau, Dwyer, and Hodson (2015)

[29] Looney and Yannelis (2015)

[30] Susan Dynarski, “Why Small Student Debt Can Mean Big Problems,” New York Times (Sept. 1, 2015), p. A-3, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/01/upshot/why-students-with-smallest-debts-need-the-greatest-help.html

[31] Federal Reserve, “Student Loans and Other Education Debt”

[32] Looney and Yannelis (2015)

[33] Sandy Baum, “Why Forgive Student Debt?”, Urban Institute: Urban Wire blog (Aug. 24, 2020), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/why-forgive-student-debt

[34] Sandy Baum and Matthew Chingos, “Extending Student Loan Relief during the Coronavirus Pandemic,” Urban Institute: Urban Wire blog (Aug. 5, 2020), https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/extending-student-loan-relief-during-coronavirus-pandemic. Similar administrative problems plague the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program: See United States Government Accountability Office, “Public Service Loan Forgiveness: Improving the Temporary Expanded Process Could Help Reduce Borrower Confusion,” GAO-19-595 (Sept. 2019), https://www.gao.gov/assets/710/701157.pdf

[35] Lawrence L. Wu and Nicholas D.E. Mark, “Has U.S. Fertility Declined? The Answer Depends on Use of a Period Vs. Cohort Measure Of Fertility,” presented at 2019 Annual Meetings of the Population Association of America, http://paa2019.populationassociation.org/uploads/191110

[36] For time trends in fertility and education, see Adam Isen and Betsey Stevenson, “Women’s Education and Family Behavior: Trends in Marriage, Divorce and Fertility,” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, No. 15725 (Feb. 2010), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w15725/w15725.pdf. The suppressive effects of education itself on fertility seem modest, but outside the scope of this paper. They seem most likely to be felt most heavily on women from disadvantaged backgrounds, who may indeed be the most likely to rely on student loans to achieve higher educational attainment. See also Jennie E. Brand and Dwight Davis, “The Impact of College Education on Fertility: Evidence for Heterogeneous Effects.” Demography vol. 48:3 (2011): 863-87. doi:10.1007/s13524-011-0034-3

[37] Note that there is still a notable gradient in first birth across education.

Paul Hemez, “Family Formation Experiences: Women’s Median Ages at First Marriage and First Birth, 1979 & 2016,” National Center for Family & Marriage Research, Bowling Green State University, FP-19-15 (2019), https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-15

[38] It should be noted that the SCF has a number of known weaknesses, including multiple adults living within the same household and variable response rates – In the 2016 SCF, “for example, the response rate decreased from approximately 50 percent at the bottom of the wealth distribution down to 12 percent at the top. This suggests that any estimates made using the SCF could suffer from selection bias.” Additionally, IRS administrative data show that the top fifth of households hold 36% of all student debt, but the SCF reports only 27%. However, it remains the most commonly used and most-useful dataset for understanding household wealth trends. For more information, see Adam Looney, “Who Owes the Most Student Debt?”, The Brookings Institution blog (June 28, 2019),https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/06/28/who-owes-the-most-student-debt/, and Kevin Carney, “Decomposing the Black-White Wealth Gap in the United States, 1989-2013,” master’s thesis (2016), http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Carney2016.pdf

[39] For family formation purposes, it makes most sense to focus on households headed by someone 22 to 50 years old.

Survey of Consumer Finances, analyzed with UC-Berkeley SDA

[40] Dora Gicheva, “Student Loans or Marriage? A look at the Highly Educated,” Economics of Education Review,

Vol. 53, (Aug. 2016,) 207-216, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.04.006

[41] Holger Sieg and Yu Wang, “The Impact of Student Debt on Education, Career, and Marriage Choices of Female Lawyers,” National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, No. 23453 (May 2017), https://www.nber.org/papers/w23453

[42] Lei Zhang, “Effects of College Educational Debt on Graduate School Attendance and Early Career and Lifestyle Choices,” Education Economics, 21:2, (2013), 154-175, DOI: 10.1080/09645292.2010.545204

[43] Charley Stone, Carl Van Horn, and Cliff Zukin, “Chasing the American Dream: Recent College Graduates and the Great Recession,” John J. Heldrich Center for Workforce Development, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Rutgers: The State University of New Jersey (May 2012), https://www.heldrich.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/products/uploads/Chasing_American_Dream_Report.pdf

[44] Erin Velez, Melissa Cominole, and Alexander Bentz, “Debt Burden after College: The Effect of Student Loan Debt on Graduates’ Employment, Additional Schooling, Family Formation, and Home Ownership,” Education Economics, 27:2, (2018) 186-206, DOI: 10.1080/09645292.2018.1541167

[45] Clifford Robb and Samantha L. Schreiber, “Married with Children? The Role of Student Loan Debt” (September 23, 2019), personal working paper, http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3458547

[46] The Baccalaureate and Beyond survey is limited to only graduates of four-year colleges, leaving out students who did not attend or did not finish college. Additionally, the Velez, Comminole, and Bentz paper relies on an instrumental variable approach that uses in-state tuition as a plausibly unrelated factor to control for debt and marriage decisions, an assumption that could be violated if a student’s post-college outcomes is correlated with a state’s level of tuition (say, if students from a state with generous levels on spending on in-state tuition were systemically more likely to opt for graduate education and defer marriage.)

[47] E.g., Sharon Sassler and Amanda J. Miller. “Waiting to Be Asked: Gender, Power, and Relationship Progression Among Cohabiting Couples.” Journal of Family Issues, 32:4 (Apr. 2011), 482–506, doi:10.1177/0192513X10391045.

[48] Andrew J. Cherlin, “The Deinstitutionalization of American Marriage,” Journal of Marriage and Family, 66:4 (Nov. 2004), 848-861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x

[49] Addo (2014)

[50] Addo (2014). For women, the difference between remaining single and both cohabiting and marriage is statistically significant at p < .05. Interestingly, Addo suggests that there was a positive association between student loan debt and marriage propensity for men in prior cohorts, as college education signaled a more desirable marriage match. That relationship now seems to have been eroded away.

[51] Robert Bozick and Angela Estacion, “Do Student Loans Delay Marriage? Debt Repayment and Family Formation in Young Adulthood,” Demographic Research, 30:69 (June 2014), 1865-1891, DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.69

[52] A working paper found suggestive evidence that student loan burdens may change decision-making along racial lines as well, and may be a particular barrier for Hispanic youth. Stella Min and Miles G. Taylor. “Racial and Ethnic Variation in the Relationship Between Student Loan Debt and the Transition to First Birth.” Demography 55,1 (February 2018): 165-188.

[53] Addo (2014)

[54] U.S. Congress, Joint Economic Committee, Social Capital Project, “Love, Marriage, and the Baby Carriage: The Rise in Unwed Childbearing.” Report prepared by Vice-chairman’s staff, 115th Cong., 1st Sess. (Dec. 2017). Social Capital Project Report No. 4-17, https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/2017/12/love-marriage-and-the-baby-carriage-the-rise-in-unwed-childbearing

[55] Robb and Schreiber (2019)

[56] Velez, Comminole, and Bentz (2018)

[57] Nau, Dwyer, and Hodson (2015)

[58] Nau, Dwyer, and Hodson (2015)

[59] Robb and Schreiber (2019)

[60] Robb and Schreiber (2019)

[61] I am indebted to Lyman Stone at the American Enterprise Institute for making this suggestion

[62] Internal Revenue Service, “Lifetime Learning Credit,” (Sept. 20, 2020), https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/llc

[63] Tara Siegel Bernard, “Paying Back Student Debt Should Be a Simpler Affair,” New York Times (Oct. 14, 2019), p. B-1, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/13/your-money/student-loans-income-repayment.html

[64] Susan Dynarski and Daniel Kreisman, “Loans for Educational Opportunity: Making Borrowing Work for Today’s Students,” Hamilton Project Discussion Paper 2013-05 (Oct. 2013), https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/legacy/files/downloads_and_links/THP_DynarskiDiscPaper_Final.pdf

[65] David A. Moss, College Access for All: Promoting Investment in Education Through Income-Contingent Lending, (2007), Tobin Project, quoted in Andrew Gillen, “Unleashing Market-Based Student Lending,” Texas Public Policy Foundation (May 2020), https://files.texaspolicy.com/uploads/2020/05/07121332/Gillen-Market-based-Student-Lending.pdf

[66] Lindsay Ahlman, “The Debt is in the Details: A Review of Existing Proposals to Streamline Income-Driven Repayment,” The Institute for College Access & Success (July 2019) https://ticas.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/debt-is-in-the-details.pdf

[67] On marriage penalties, see: Bradford Wilcox, Chris Gersten and Jerry Regier, “Marriage Penalties in Means-Tested Tax and Transfer Programs: Issues and Options,” Office of Family Assistance, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Report 2019-01, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ofa/hmrf_marriagepenalties_paper_final50812_6_19.pdf. Patrick Brown, “Expanding Child Care Choices: Reforming the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit to Improve Family Affordability,” U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, (February 2021), https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/analysis?ID=0A45EA4E-15A1-4EAA-A97E-9F649A53DF84

[68] Riley Galton, “Universities Need to do More to Support Grad Student Parents,” Science (Sept. 12, 2019), doi:10.1126/science.caredit.aaz4731

[69] U.S. Congress, Senate, “Higher Education Reform and Opportunity Act of 2019,” S.2339, 116th Cong., 1st sess.,introduced in Senate, July 30, 2019.

[70] Gillen (2020)

[71] Sandy Baum, Kristin Blagg, and Rachel Fishman, “Reshaping Parent PLUS Loans: Recommendations for Reforming the Parent PLUS Program,” Urban Institute, (April 2019) https://s3.amazonaws.com/newamericadotorg/documents/2019_04_04_Reshaping_Parent_PLUS_Loans_finalized.pdf.

[72] Jamie Hall and Mary Clare Amselem, “Time to Reform Higher Education Financing and Accreditation,” The Heritage Foundation, Issue Brief No. 4668, March 28, 2017 https://www.heritage.org/sites/default/files/2017-03/IB4668.pdf

[73] Oren Cass, “How the Other Half Learns: Reorienting an Education System That Fails Most Students,” Manhattan Institute, (Aug. 2018), https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/sites/default/files/R-OC-0818.pdf

[74] Jason D. Delisle, “Reforming Student Loans and Tax Credits,” in “Policy Reforms to Strengthen Higher Education,” National Affairs [ed.] (2017), https://nationalaffairs.com/storage/app/uploads/public/doclib/HigherEd_Ch2_Delisle.pdf

[75] Mark P. Keightley, “An Economic Perspective of Income Share Agreements,” Congressional Research Serivce, IF11249, July 15, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF11269.pdf

[76] U.S. Congress, Senate, “ISA Student Protection Act of 2019,” S.2114, 116th Cong., 1st sess.,introduced in Senate, July 15, 2019, https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/2114?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22ISA+Student+Protection+Act+of+2019%22%7D

[77] Moreover, more aggressive moves to reduce or eliminate student debt raise significant questions of horizontal equity. This would subsidize the debts incurred by some individuals across many others who made sacrifices or took different paths so as to avoid being burdened by debt. Policy can ameliorate specific financial circumstances without overreacting to the challenges facing a number of households as a result of the trade-offs they have made. Proposals to forgive student debt without changing how higher education is financed would rigidify a status quo and forgo an opportunity to reorient public policy to support family formation. Large-scale forgiveness may temporarily alleviate some short-term burdens without doing anything to make it easier for more couples to marry and have kids in the medium- and long-term.

Patrick T. Brown is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where his work with the Life and Family Initiative focuses on developing a robust pro-family economic agenda and supporting families as the cornerstone of a healthy and flourishing society.