Published May 24, 2018

When English lyric poetry is the subject, one thinks first of the Romantics. To many readers for whom poetry is not a life-sustaining staple, and even to some for whom it is, the Romantics have come to define poetry’s very essence: the eruption of exorbitant feeling too rich for the heart to contain in silence. Readers better versed in older and more recent poetry may downgrade Romantic extravagances in favor of, say, the brainy eroticism of John Donne, the eviscerating wit of Alexander Pope, or the chill austerity of Geoffrey Hill. Yet there is no denying that the two poetic generations that thrived from the 1790s to the 1820s represent an artistic efflorescence surpassed in English literature only by that of Shakespeare and his contemporaries.

Although they may be herded together to mark a period or even a movement, each of the Romantics was a singular figure. In the first generation, whose principals outlived those of the second, William Blake, almost unknown in his day, couched shattering curses and blessings in language of disarming simplicity, and conceived theogonies and prophecies intended to rival or even supplant the Bible. Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth joined forces in the collection Lyrical Ballads (1798) “with a view to ascertain how far the language of conversation in the middle and lower classes of society is adapted to the purposes of poetic pleasure.” Coleridge took opium as more conventional gentlemen took snuff and gave birth to fantastic visions, while Wordsworth made heroes of leech gatherers and idiot boys and mourned the loss of “the visionary gleam” in a world hellbent on “getting and spending.” In the second generation, Percy Bysshe Shelley took the lash to a political, social, and religious order that bred human depravity and abjection, and he proclaimed the glorious coming day when freedom and true worship will make a heaven on earth. John Keats, bound for a consumptive’s early grave, kept house with rapturous melancholy and “beauty that must die.”

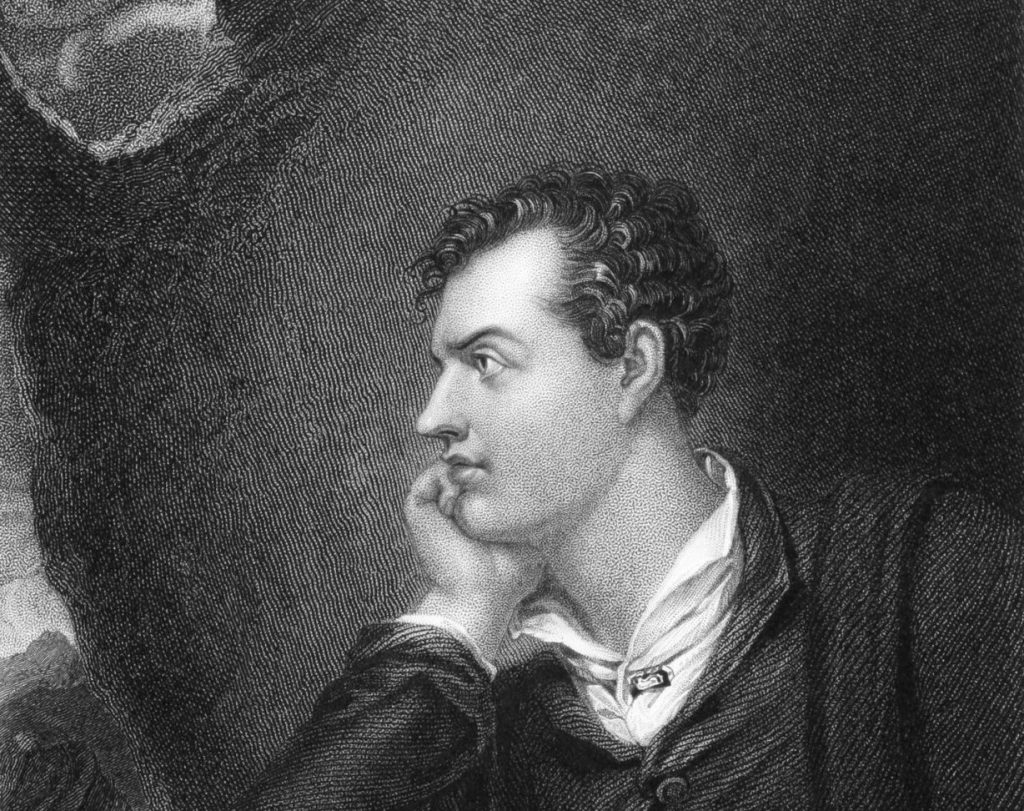

And then there was Lord Byron (1788-1824), the most famous poet of his time and the most notorious hellion, whose life and work together created the superb desperado known as the Byronic hero, dubious exemplar for numerous impressionable young souls bent on artistic glory, sensual feasting, and political high daring, overlaid with world-weariness that made all such aspirations seem ultimately and deliciously pointless. Byron set himself at a haughty remove from the other Romantics. An aristocrat’s vanity informed and undercut Byron’s sense of literary vocation, so that he deprecated his own poetry as inferior to heroic action and simply dismissed that of his most estimable contemporaries.

In the long satire English Bards and Scotch Reviewers, published when he was 21, Byron laid waste to his most distinguished elder, whose studied plainness of diction and commonness of subject he found noisome: “Yet let them not to vulgar Wordsworth stoop, / The meanest object of the lowly group, / Whose verse, of all but childish prattle void, / Seems blessed harmony to Lamb and Lloyd.” In an 1814 letter to his friend James Hogg, he declared that Wordsworth missed his true calling as “a man-midwife” and allowed that Coleridge was the best of the Lake Poets—“but bad is the best.” Writing in 1820 to his publisher, John Murray, he sneered at “Johnny Keats’s p-ss a bed poetry” and then at the poor doomed youngster’s

mental masturbation—he is always f-gg-g his Imagination.—I don’t mean that he is indecent but viciously soliciting his own ideas into a state which is neither poetry nor any thing else but a Bedlam vision produced by raw pork and opium.

And in an 1817 letter to Murray, Byron condemned the whole Romantic lot, himself included: “Scott—Southey—Wordsworth—Moore—Campbell—I—are all in the wrong—one as much as another—that we are upon a wrong revolutionary poetical system—or systems—not worth a damn in itself.” Sizing up even his own poems beside those of Alexander Pope, past master of the heroic couplet that sliced like cold steel, he found them stunted and hopelessly flabby: “I was really astonished (I ought not to have been so) and mortified—at the ineffable distance in point of sense—harmony—effect—and even Imagination Passion—& Invention—between the little Queen Anne’s Man—& us of the Lower Empire.”

It might appear then that Byron was a classical poet manqué, hardly a Romantic at all, or an unwilling one at best. Yet in fact he defined the species of Romanticism that had the most profound effect on artists and political firebrands of the era, not only in England but throughout Europe, and that has persisted into our own time. Although he was a man apart, indeed an outcast and an exile for much of his life, many wanted to be just like him; and why not? He was dashing, adventurous, rich, handsome, catnip to women, lionized by the great world yet despising its blandishments. From a safe distance the allure might seem irresistible. Being Byron, however, was quite a different matter from wanting to be Byron.

George Gordon Byron was born in London on January 22, 1788. His father, Captain John Byron, late of the Coldstream Guards, was known as Mad Jack to his fellow soldiers. He had been married before, after a scandalous adultery and elopement, and had fathered a daughter, Augusta, who was four years older than her half-brother. Mad Jack saw little of his son, decamping to France to elude creditors, and he died there in 1791, perhaps a victim of tuberculosis, perhaps a suicide by poison. As the excellent biographer Fiona MacCarthy writes in Byron: Life and Legend (2002),

A friend visiting [Byron’s home] Newstead when he was a young man remembered how, “while washing his hands, and singing a gay Neapolitan air,” Byron had suddenly turned round, announcing that there had always been madness in the family and that his father had cut his throat.

MacCarthy prefers not to cause a stir about Byron’s torturous family history and his own distressing condition. But Kay Redfield Jamison, professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins, coauthor of the definitive textbook on manic depression and herself a sufferer from the illness, makes Byron’s mental disease the centerpiece of her invaluable book Touched with Fire: Manic-Depressive Illness and the Artistic Temperament (1993), and she emphasizes the genetic fatefulness of his inheritance from both sides of the family. Byron, she writes, “had a family history remarkable for its suicide (in itself more likely to be associated with manic-depressive illness than with any other condition), violence, irrationality, financial extravagance, and recurrent melancholia.” Doom was inscribed in his bloodline, and he knew it. Jamison cites several remarks Byron made to intimates about the emotional turbulence passed to him down the generations: “My melancholy is something temperamental, inherited.” “I am not sure that long life is desirable for one of my temper & constitutional depression of Spirits.” According to Jamison, Byron cycled regularly between elation and despair, and he suffered most intensely from what psychiatrists call a mixed state, which combines mania’s fearsome energy presenting as “morbid irritability of temper” (in Byron’s own self-description) with depression’s sepulchral desolation.

His prodigious gifts were weighed down by his painful liabilities. The gods smiled on him benevolently only to break into laughter at their cunning cruelty. He had a noble title and great wealth inherited from his great-uncle when he was 10; he also had a clubfoot that was an unforgivable affront to his colossal vanity. Rare beauty of face and figure here, insatiable satyr-like sexual compulsion there. Winning amiability that made him beloved by his friends, hair-trigger irascibility that made him a horror to himself and especially to his wife. Jamison sums up brilliantly the difference between the Byron that the public saw or imagined and the man he actually was:

The “Byronic” has come to mean the theatrical, Romantic, brooding, mock heroic, posturing, cynical, passionate, or sardonic. Unfortunately, these epithets suggest an exaggerated or even insincere quality, and in doing so tend to minimize the degree of genuine suffering that Byron experienced; such a characterization also overlooks the extraordinary intellectual and emotional discipline he exerted over a kind of pain that brings most who experience it to their knees.

Although Byron surely would have preferred to forgo the worst emotional turmoil he suffered, the driving force of his temperament was the craving for experience, the more intense and extreme the better. To convince himself he was really alive strong jolts of pleasure and pain were required.

By Byron’s lights what most people did with the brief time they had on earth did not qualify as living. Death was perhaps not an unrelenting fear but it was a continual presence and a goad to vital spirits. A human skull set in silver served as his drinking cup—a grinning memento mori to enhance the fleeting joys of dissipation. Carousing was a way of life, and of holding off the threat of extinction. Ardent male friendships at Harrow and Cambridge flared into homosexual romances, and Byron’s love for a Trinity College chorister became a consuming blaze; yet when John Edleston died of tuberculosis in 1811, Byron, who heard of the death while he was on a two-year Grand Tour with friends, could not summon grief appropriate to the occasion: Remembering “one whom I once loved more than I ever loved a living thing. . . . I had not a tear left for an event which five years ago would have bowed me to the dust.” Desiccation of feeling was the obverse of emotional overload.

He wanted to feel intensely more than he wanted anything else. In 1813, courting by letter the woman he would marry but did not love, Annabella Milbanke, Byron professed his creed in a fevered rush: “The great object of life is Sensation—to feel that we exist—even though in pain—it is this ‘craving void’ which drives us to Gaming—to Battle—to Travel—to intemperate but keenly felt pursuits of every description whose principal attraction is the agitation inseparable from their accomplishment.” As he was writing this, the woman he did love was clearly in his thoughts: his half-sister, Augusta Leigh, with whom he was having an affair and who was the female passion of his life. The frightful emotional rip-current pulled him into treacherous deeps and he was sunk full fathom five.

His marriage to Annabella in 1815 was a mockery and a mutual torment. His friend Samuel Rogers remembered reading a passage from Byron’s memoir, which was burned for sanitary reasons after his death: “On his marriage-night, Byron started out of his first sleep; a taper, which burned in the room, was casting a ruddy glare through the crimson curtains of the bed; and he could not help exclaiming, in a voice so loud that he wakened Lady B. ‘Good God, I am surely in hell!’” He made sure he had company there. Flaying Annabella could not relieve his misery but did acutely increase hers. He told her that he was “more accursed in marriage than any other act of his life,” that “one animal of the kind was as good to him as another,” and he hinted darkly at his homosexual and incestuous past. When the couple went to stay with Augusta, the hints became unmistakable tracks leading to perdition. Byron would stretch out on the sofa and instruct his two women to take turns kissing him; it was plain to Annabella that he and Augusta were enjoying the game more than she was. The marriage lasted barely a year before the couple separated for good.

When Annabella filed for divorce on grounds of Byron’s insanity, her testimony saw to it that his rakehell reputation got around, and fear of the law compelled him to depart England. Sodomy was a hanging offense, and although incest strangely enough was not a criminal act, it remained nevertheless not quite acceptable in polite society. Bound for the continent never to return, Byron saw his wife and daughter, Ada, and his sister and her daughter, Medora, who may have been his as well, for the last time.

Italian mores, which made adultery commonplace, gave him a reprobate’s sexual license. In Venice over a three-year period he slept with 200 women by his own count, toting up a fraction of them in a letter to friends that, as MacCarthy remarks, reads like Leporello’s catalogue aria from Mozart’s Don Giovanni: “the Taruscelli—the Da Mosti—the Spineda—the Lotti—the Rizzato [the list goes on] . . . some of them are Countesses—& some of them Cobblers wives—some noble—some middling—some low—& all whores.”

He established a more lasting attachment, as such things go, to Countess Teresa Guiccioli, the beautiful 19-year-old wife of a man pushing 60; and he wrote professions of undying love to Augusta in which he pricked her with reports of his various sexual entanglements. On his travels he met and befriended the poet Shelley, whose militant hatred of Christianity and the scandal of his deserted first wife’s suicide made him, too, unwelcome back home. Before leaving England, Byron had impregnated Shelley’s second wife’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont. “I never loved nor pretended to love her—but a man is a man—& if a girl of eighteen comes prancing to you at all hours—there is but one way.” Claire and her child became members of the Shelleys’ peripatetic household, and Byron sedulously ignored Claire when they met again in Italy, while he clapped their daughter, Allegra, into a convent school for the good of her soul, which was endangered by the Shelleys’ unspeakable irreligion. The little girl died there at the age of 5, and while Byron had not visited his child for a year his sorrow and remorse appear to have been genuine.

But then losses were to be expected. When Shelley drowned in a boating accident—the sailboat was named Don Juan—Byron performed the obsequies after his own fashion by swimming far out to sea as his friend’s corpse was being cremated on the beach.

Erotic misadventures and mere poetry were growing tiresome for Byron; dreams of military and political heroism of the highest order had always fascinated him. He had written in his journal in 1813: “To be the first man—not the Dictator—not the Sylla, but the Washington or the Aristides—the leader in talent and truth—is next to the Divinity! Franklin, Penn, and next to those, either Brutus or Cassius—even Mirabeau—or St. Just.” Nothing less than founding a free nation now became his fantasy. “It is a grand object, the very poetry of politics. Only think—a free Italy!” Byron plotted war against the Austrian oppressor as a conspirator with the revolutionary Carbonari, using his house in Ravenna as a secret arms depot. But the Italians’ fecklessness when the opportunity for successful action arose disillusioned him for good: They were better at making operas than revolution.

To liberate Greece from its cruel Turkish masters, however, remained an undying hope; the Greek war of independence had begun in 1821, and he pictured himself playing a key role there in restoring freedom to its birthplace. In June 1823 Byron sailed as a representative of the London Greek Committee to the Ionian island of Cephalonia, which was ruled under a British protectorate. In his journal he roused himself with poetry to prove by mighty deeds that he was more than a poet: “The Dead have been awakened—shall I sleep? / The World’s at war with tyrants—shall I crouch? / The harvest’s ripe—and shall I pause to reap? / I slumber not—the thorn is in my Couch— / Each day a trumpet soundeth in mine ear— / It’s Echo in my heart.”

Prince Alexander Mavrocordato, the first Greek president under the constitution of 1822—though on the outs with the military leadership—wrote to Byron as though he were the conquering hero finally come: “You will be received here as a savior. Be assured, My Lord, that it depends only on yourself to secure the destiny of Greece.” His reputation as a poetic apostle of freedom evidently invested him with authority as a fighting man.

In 1824 Archistrategos—commander in chief—Byron assumed generalship of 600 troops on the mainland in Missolonghi, whom he paid out of his own pocket. Plans for an audacious attack on Lepanto came to nothing as needed rockets did not arrive and the soldiers proved refractory at best. The archistrategos was left with a bodyguard of 50 men. Fiasco everywhere. His unrequited love for a comely adolescent page distracted him from the appointed task, and he recorded the effort to overcome himself in the poem “On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year”:

Tread those reviving passions down,

Unworthy manhood!—unto thee

Indifferent should the smile or frown

Of beauty be.If thou regrett’st thy youth, why live?

The land of honourable death

Is here:—up to the field, and give

Away thy Breath!

Death would come soon enough, that April, though not in the field: An infection with fever, severe headache, and rheumatic pains was treated with bloodletting that drained nearly half the blood in Byron’s body; the infection might have proved fatal, but the attempted cure certainly was.

It is astonishing that, living as he did, Byron found time to write at all; more astonishing still that the Oxford edition of his Poetical Works runs to some 900 pages of very small print in double columns. Byron was exceedingly proud of being a man who knew the world as few men—and very few poets—do, and the poetry shows the range of his experience, if also the limitations of the mind and sensibility that reflect on that experience. He wrote fizzy squibs; comic epitaphs; ironic Horatian bijoux; laments of a man crossed in love; numerous lyrics of lovers’ sad parting; speculations on the fate of the soul after death; metaphysical panoramas of universal devastation; encomia to Napoleon and denunciations of the blood-soaked ogre he became; rants against tyranny and homages to republican virtue; breakneck narratives about honorable manly violence and death-defying courage, which alone makes life worth living; closet dramas rife with nihilist sorcery, biblical murder, and Orientalist fleshpots.

Reading Byron’s poetry in the light of his life, one has the abiding sense of a man only too aware of his weakness and folly fending off an unbearable sorrow. He has seen too much and felt far too much and he knows the damage done is incalculable and unforgivable. In the poignantly lovely “She walks in beauty,” he is ravished by a purity that he has forsaken forever, and this grave tribute to moral excellence joined with physical splendor tacitly mourns the life and love he should have had:

And on that cheek, and o’er that brow,

So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow,

But tell of days in goodness spent,

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!

This overriding feeling of tragic waste takes various forms. In “The Siege of Corinth” Byron renders the macabre indignity of death in battle with emetic gusto, so that the reader knows what it means to be left for the dogs; the balladeer’s incantatory rhythm makes one think of Kipling at his best:

From a Tartar’s skull they had stripp’d the flesh,

As ye peel the fig when its fruit is fresh;

And their white tusks crunch’d o’er the whiter skull,

As it slipp’d through their jaws, when their edge grew dull,

As they lazily mumbled the bones of the dead,

When they scarce could rise from the spot where they fed.

In Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, the exotic travelogue and meditation on a life quite like Byron’s own—an epic poem that made him instantly famous—the narrator not readily distinguishable from the author confesses to a disorderly mind and heart that have blighted his existence, yet summons the will to carry on when the best chance he had at happiness has been spoiled:

Yet must I think less wildly:—I have thought

Too long and darkly, till my brain became,

In its own eddy boiling and o’erwrought,

A whirling gulf of phantasy and flame:

And thus, untaught in youth my heart to tame,

My springs of life were poison’d. ’Tis too late!

Yet am I changed; though still enough the same

In strength to bear what time cannot abate,

And feed on bitter fruits without accusing Fate.

In Cain: A Mystery, however, Fate does stand accused, as the impulse to primal murder comes from hatred of what God has made man: “For what must I be grateful? / For being dust, and groveling in the dust, / Till I return to dust? If I am nothing— / For nothing shall I be an hypocrite, / And seem well-pleased with pain?” Contemptuous of hypocritical reverence for an unloving God even as he was bemused by thoughts of eternity, Byron made his peace with nihilism, as one sees in his response to Annabella’s efforts to foist godliness on him: “Why I came here—I know not—where I shall go it is useless to enquire—in the midst of myriads of the living & the dead worlds—stars—systems—infinity—why should I be anxious about an atom?”

When W.H. Auden honored Byron as “the master of the airy manner,” he must have been thinking above all of the style of Don Juan (the second word pronounced with two syllables, JOO-uhn). There one hears the winning voice of gamy urbanity—that of a man who has seen all that the world holds and who may be appalled at the spectacle but is even more amused by it. His moral discernment issues in mordant gaiety. Witness the nicely calculated working of this stanza, its sinuous machinery unobtrusively cranking up the blade of judgment that drops like fatality with the final word, utterly unexpected and utterly perfect:

And now he rose; and after due ablutions

Exacted by the customs of the East,

And prayers and other pious evolutions,

He drank six cups of coffee at the least,

And then withdrew to hear about the Russians,

Whose victories had recently increased

In Catherine’s reign, whom glory still adores,

As greatest of all sovereigns and whores.

In this unfinished masterpiece there is the lightness of a mind at play that one is hard-pressed to find elsewhere in Byron. To John Murray he wrote of Don Juan in 1821, “But I had not quite fixed whether to make him end in Hell—or in an unhappy marriage,—not knowing which would be the severest.—The Spanish tradition says Hell—but it is probably only an Allegory of the other state.” A proud man’s joke at his own expense; but Byron took his own suffering seriously enough to know what real hell is, and most of his poetry is shot through with pain. He was the saddest of the English Romantics and, for all his singular pathology, the one who foretold most strikingly our own disorder.

Algis Valiunas is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a contributing editor at the New Atlantis.